Sadamasa Motonaga by Tamsen Greene

Sadamasa Motonaga was an early member of the Gutai group, a postwar Japanese art movement in which a generation of artists, deeply affected by the destruction of the war and the atomic bomb, radically upended traditional approaches to art. The timing of Motonaga’s current exhibition at McCaffrey Fine Arts, his first solo show in New York since 1961, anticipates a major retrospective of Gutai at the Guggenheim next February, in which Motonaga will be included.

Gutai is often aligned with performance and installation but Motonaga, who did experiment beyond the canvas mostly with ephemeral installations of colored liquid suspended in plastic, considered himself foremost a painter. The exhibition at McCaffrey focuses on eight paintings ranging from 1958-2004 (the artist died in 2011). Through this tight retrospective, it is easy to track the development of Motonaga’s unique style. The exhibition begins with two paintings from 1958, each made with poured paint in primary colors mixed with synthetic resin resulting in rich pools of pigment alongside more delicate drips, stains, and brushstrokes. There is a joyful improvisation in these works and the liberating arc of a full-body gesture, akin to the parallel explorations of Abstract Expressionism.

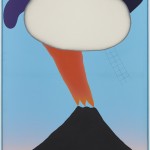

While these paintings are proficient, it is in his later work that Motonaga develops a lexicon of figures that hover between anthropomorphic geometry and “kawaii” cartoons. In “Fufuhaha,” 1979, and “Line,” also 1979, whimsical characters such as a bug-like triangle with scuttling legs, or a curled fist-like shape that looks like a two-dimensional Jean Arp, inhabit groundless worlds of scratches, stipples, and spray paint. A sense of experimentation abounds but the work feels ebulliently resolved. It is also prescient of what would become the defining Japanese style of contemporary art – the worlds of Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara, and the Kaikai Kiki studio. This is underscored in other works such as “Sakuhin,” 1978, a pared down composition where a floating large round circle looms over Mount Fuji like a cartoon head with licks of red joining it to the black jagged peaks for the mountain. This work seems to anticipate Murakami’s ideas of Superflat, the slick, surface handling of paint that his studio has become known for.

Despite visual parallels with these artists, Motonaga’s world seems free from the sexualized overtones and angst of the later Japanese artists, more like a Shel Silverstein book than a saucy manga. In a time when feelings of anger, impotence and frustration were pervasive in Japan, these painting feel soothing, almost healing. This is especially present in “Lya lya,” 1972, where a large oblong, blimp shape drifts in a white sky, like a giant pill. The shape is featureless yet seems benign and protective. Other paintings are extremely joyful, such as “Sakuhin,” 1964, an incredible, transitional painting in which Motonaga’s future style literally bursts from his former work. Figures that are just starting to differentiate themselves from abstraction are born from poured forms reminiscent of Morris Louis. In this painting we see Motonaga deeply engaged with abstraction yet already thinking about the forms that will soon inhabit his oeuvre. Sometimes artists are not well known in the United States because they are minor. This is not the case with Motonaga and most of Gutai. Japan possesses deep troves of artists lesser known in the West due more to politics than prowess. Now it’s our turn to get to know them better.

Tags: Journal