Feature: Dark Clouds and Bright Futures: Current Climates in Australian Aboriginal Art

After a busy two months of exhibition openings, art fairs, national awards and international recognition, something this year was missing from the usually dynamic Aboriginal art circuit. Some have blamed the bureaucracy, some have blamed the institutions, some have blamed the slumping market, and some have blamed the curators without knowing all the facts. However, is there any benefit in blaming anyone? Artists are constantly surprising us, experimental and courageous, more innovative than ever, more vocal then ever, this should be a time of celebration.

The diversity of Aboriginal art across Australia can no longer be contained, there is no simple way to present or engage with Aboriginal exhibitions. Different multiplicities are operating across the vast and intricate expanse of Australia. There is more opportunity for collaboration and discussion. It is impossible to capture this diversity in one exhibition, in one retrospective, in one institution. The only way to talk about these pluralities is to create multiple structures that not only recognizes this plurality, “but provide a means through which plurality can be ordered, characterized and evaluated” and perhaps communicated in some meaningful way. (II) The future of Aboriginal art may be facilitating new ways of capturing plurality through the mobilization of fluid networks and information sharing. This will take a keen ear and an open mind, it has started happening all ready from those whom treat all artists as artists.

There is a degree of tension looming between those who are keen to write Aboriginal arts obituary and the artists themselves, whom are still creating, very much alive. The only thing that is becoming extinct is homogeneity, the view that all art looks and is about the same thing. Stories are now more personal, more individual, more contemporary and in some ways, more confronting. Exhibitions have previously come to celebrate the abstract mysteries of ‘other worlds,’ but where are these other worlds and who is in them? As Hetti Perkins remarks, are we doomed to continually rearrange the seats on a sinking Titanic? (XIII) For some people it is still unthinkable that Aboriginal art can be on the one hand traditional and on the other contemporary. (IV) However, as Rex Butler explains, Aboriginal art is the one thing in Australia that involves us as it is “truly alive, has wider implications, that tells us something about the times in which we live.” (V) Stephanie Radock, almost 10 years later is saying a similar thing, “Aboriginal history, Australian history, world history of great significance.” (XIV) Any deviations or attempts at shaking things up, cross cultural collaborations and solo careers are usually met with harsh criticism, seemingly like some people have missed the point. Ian McLean explains that modernity’s apocalyptic effects on all traditional societies are undeniable and that Aboriginal art in Australia is laying bare these effects for collaborative interaction, so why aren’t we interacting? (XI) The silence surrounding colonialism and aboriginal experiences of it continues to silence voices in Aboriginal art. (IX) As Tim Acker explains, “The market’s focus on the consumption of art and the profitability of its players has smothered serious and confronting issues of artist and community livelihoods.” (I) Some of the best contemporary art has been created from issues of displacement, migration, marginalization; “great art happens in spite of its circumstances, rather than because of them.” (VIII) It seems that Aboriginal art is often theorised from the point of view that it is all ready ‘dead,’ that is has remained unchanged for thousands of years, that this complex culture has not had to constantly reinvent itself to remain in tact in some way. An important part of this reinvention and rejuvenation has come from the making of art, an art making that is “process oriented and not outcome oriented,” (IV) so why is everybody so obsessed with the outcome?

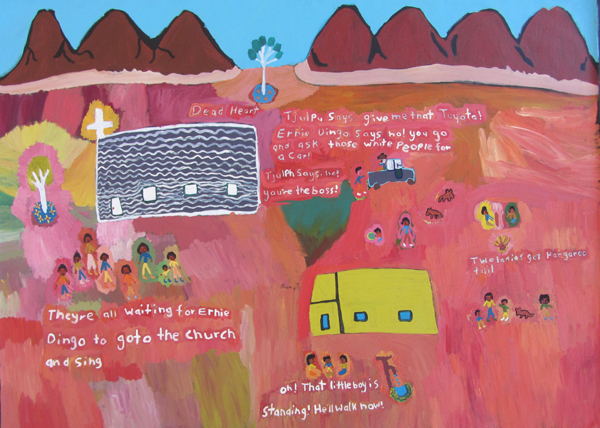

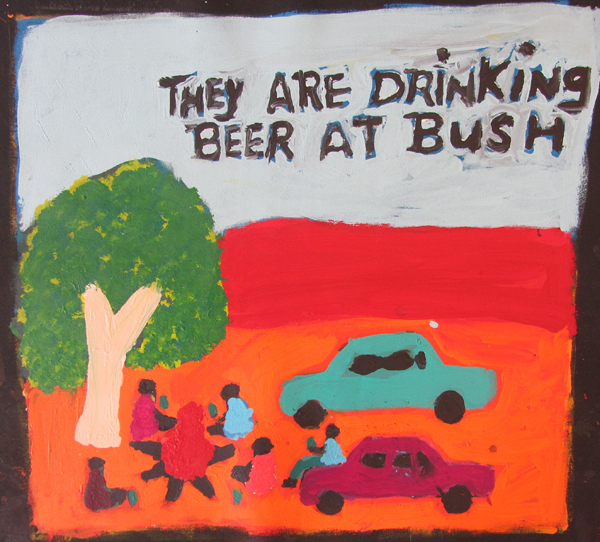

I believe there is reason to believe that artists want things to be done differently, that stories need to be shared so that they can be acknowledged. As Djon Mundine states, it is not about forgiveness, it’s about recognition and remembering. (XII) When looking at a selection of different artists across Australia, with a list that is constantly expanding, it becomes clear that the work itself demands something else, at the very least, a willingness to listen. Sally Mulda, Margaret Boko and Dulcie Sharpe all work in Alice Springs under the banner of Tangentyere Artists and Yarrenyty-Arltere. Their work talks of intervention, reinvention and collisions, experimental art works that are innovative microcosms of the world they live in. Lance Chad and Billy Kenda paint at the human rights organization, Bindi Inc., also in Alice Springs. Lance’s paintings of cowboys have a haunting, surrealist quality where Billy’s bold and vibrant tourist scenes come from deeply personal observations.

Sally M. Mulda, They are drinking beer at bush, 2012, courtesy of Tangentyere artists, copyright of the artist

I believe there is reason to believe that artists want things to be done differently, that stories need to be shared so that they can be acknowledged. As Djon Mundine states, it is not about forgiveness, it’s about recognition and remembering. (XII) When looking at a selection of different artists across Australia, with a list that is constantly expanding, it becomes clear that the work itself demands something else, at the very least, a willingness to listen. Sally Mulda, Margaret Boko and Dulcie Sharpe all work in Alice Springs under the banner of Tangentyere Artists and Yarrenyty-Arltere. Their work talks of intervention, reinvention and collisions, experimental art works that are innovative microcosms of the world they live in. Lance Chad and Billy Kenda paint at the human rights organization, Bindi Inc., also in Alice Springs. Lance’s paintings of cowboys have a haunting, surrealist quality where Billy’s bold and vibrant tourist scenes come from deeply personal observations.

Sophie Wallace, Art Centre manager at Yarrenyty Arltere explains that the degree to which people are often marginalized in Alice Springs cannot be overstated. The art produced comes directly from the heart, turning personal reflections political and social narratives. Often being written off as naive or worse, untraditional, there is always a persistence to categorize Aboriginal art, to name it one thing or another. Jorgensen explains that Aboriginal artists have always wanted to translate their paintings to a white audience so that we can understand the artist’s spiritual links to country. (IX) The spiritual power of country is still present in the grandiose of Margaret and Sally’s landscapes, but country has become more personal, a meditation on life in the town camps.

Dulcie Sharpe from Yarrenyty-Arltere is most recognized for making utterly unique soft sculpture from recycled woolen blankets. The fabric is dyed with local plants, tea and rusty bits of metal, creating rare organic patterns. Art Centre manager Sophie Wallace says the artists create work that is “humorous and beautiful, rough and sculptural, ridiculous, dramatic and inspiring… people find a voice that tells the wider community that they are worth listening to, that they are important, that they are healing themselves and their families.” (XVI)

Moving across to the Pilbara reside two sisters with a passion for innovation. Lily Long and Amy French are two Warnmun women whom paint at Martumili artists. A dynamic duo, these two began painting with the intention of modernizing their culture, sharing their ideas on canvas by always negotiating what should be included and what shouldn’t. Lily and Amy are strategists, intellectually deciphering their problems with what way best to paint. Their paintings are never one-dimensional, one thing is never one thing, having a collaborative approach and sharing the burden of the past by re-envisioning/ re-invigorating place.

Daniel Beeron and Leonard Andy from Girringun Arts in Far North Queensland universalize their personal stories. Creating small projects with big ideas, these two artists are challenging the way rainforest people have been visualized in the psyche of Aboriginal Australia and their own struggle for a unique identity. The artists only started working in 2009 and decided that the best way to create was to be radically different. Passionate and inventive, these two men from different areas are both initiating their own projects to educate both Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal audiences.

Amy French and Lily Long explaining the imagery and singing in their 5 x 3m canvas that will be featured in “We Don’t

Need a Map,”an exhibition in November, photo credit: Gabrielle Sullivan, courtesy of Martumili Artists.

Daniel Beeron has just completed the first phase of a research and visual art project about communication and connection. (VI) Daniel started with archival anthropological historical information about muwaga (message sticks) and mindil (woven) baskets from the region of tropical north Queensland. Written in early contact time, the historical information explains that without a written language, groups in that area of Australia use to communicate with message sticks. Some were carved or ornamented and were interpreted differently depending on spiritual knowledge and could also be used as a passport. Daniel explains that this project is revitalizing culture, reengaging with the past to re-articulate the future, reconnecting groups across the region and teaching younger generations. Each artist that participates creates two message sticks and two baskets, one for themselves and one for exhibition. Each is a very personal manifestation of the historical information and their own experiences. But grouped together, Daniel’s project speaks of universal truths, what can we learn from lost histories, about reconnection, about innovation and the power of personal stories in painting a much grander picture.

Leonard Andy is from Mission Beach and is one of the only few traditional elders of the land in that area. In the corner of the Cairns Regional Gallery last year, in an exhibition curated by Avril Quail, was a set of five eloquently executed and meticulously painted boomerangs. A dog with dollar signs painted on his body caught my attention, and as you delve deeper into the seemingly small, humble objects, a big story appears. Leonard explains that the story painted on the boomerangs is about cyclone money and the impact its had on the social structure of Mission Beach after the devastating cyclone Yasi tore through the region in 2010. Leonard also says that as a far north Queenslander, he is the minority of the minority, in a constant battle for a separate identity to desert Aboriginal art and culture. These artists are just at the beginning of their journey; their projects can only grow as people become more aware of the different contemporaneity’s within Australia.

Stan Brumby from Halls Creek Art Centre, Yarliyil and Mervyn Street from Mangkaja artists, Fitzroy Crossing paint about the pastoral industry and the seamless transitions made by many Aboriginal men from nomadic life to horsebacks and mustering. Described as Aboriginal cosmopolitans, young men became proficient cowboys, “fearless, full of initiative and very quick to adapt.” (X) These two artists combined a life of hard work, maintaining traditional ties and now, articulating their life on canvas in vibrant collisions. Elements of Catholicism haunt Stan’s work, his intricately executed “Noah’s Arc, 2011” is the perfect example of this consolidation. How elements of the colonizers culture was integrated, incorporated into the complex systems of Aboriginal spirituality.

Loreen Samson from Roebourne and Charmaine Green from Yamitji both are visually reacting to the reality of mining, the destruction it creates and working through their own grievances. Loreen’s figurative works envisage parts of Australia that are unseen in the cities, the industrial machinery that haunts the once pristine landscape. Charmaine’s work is full of emotion, as a way to experience the pain and facilitate a new form of activism.

After nearly 40 years the Aboriginal art movement continues to grow, artists are more committed and the art keeps evolving in unexpected ways. (X) The unreality of the ‘Australia’ presented through movies and documentaries on colonial times is very different to the Indigenous experience of Australia. If we are to be taken as seriously addressing the problems of the Aboriginal Australia divide, then we need to curate exhibitions that address this, and start a dialogue, not end one.

Aboriginal art continuously involves us because it is the site of unprecedented “cultural conflict and exchange.” (V) In the following years, it will be interesting to see how these artists develop, how disparate parts of Australia can be reconciled. This is not a uniquely Australian thing, Indigenous populations internationally are attempting to rewrite their own histories and receive acknowledgement. (XV) To use Djon Mundine’s words again, “in Aboriginal society all art is a social act,” you cannot remain neutral in the presence of these artists work. There are many artists whom are developing new ways of creating; this movement will continue to grow. This is just the beginning of the conversation that the artist’s have started, its time we all got involved.

I Acker, Tim, “Aboriginal art is a complicated thing’, Artlink 2:3, 2008, p. 64-69.

II Smith, Terry, “What is Contemporary art?” University Of Chicago Press, 2009.

III Biddle, Jennifer, “Art Under Intervention: The Radical Ordinary of June Walkutjukurr Richards,” Art Monthly, June 2010.

IV Biddle, Jennifer, via email correspondence, 2012.

V Butler, Rex, “An End of ‘Aboriginal’ art and the shock of the new” (2003) in How Aboriginies created the idea of contemporary art, ed. McLean, I., IMA Press: Australia, 2012.

VI Girrungen Arts Statement, 2012.

VII Jorgensen, Darren, “Aboriginality, hyper-visibility and wobbliness in paintings from Australia’s Western Desert,” World Art 1:2, 2011, p. 259-272.

VIII Jorgensen, Darren, “Bagging Aboriginal Art,” Arena 111, March-April, 2011, p. 38-42.

IX Jorgensen, Darren, “On Cross- Cultural Interpretations of Aboriginal Art’, Journal of Intercultural Studies 29:4, 2008, p. 413-426.

X McLean, Ian, “Aboriginal Cosmopolitans: A Prehistory of Western Desert Painting,” Globalization and Contemporary Art, ed. Harris, J. Wiley- Blackwell: UK, 2011.

XI McLean, Ian, “Aboriginal Modernisms in Central Australia,” Exiles, Diasporas and Strangers, ed. Mercer, K. MIT Press: USA, 2008.

XII Mundine, Djon, “The Ballard of Jimmy Governor,” Artlink 32:2, 2012.

XIII Perkins, Hetti, “A Place of our own: conversation with Daniel Browning,” Artlink 32:2, 2012.

XIV Radock, Stephanie, “Making Histories,” Artlink 32:2, 2012.

XV Thompsen, Christian, 2012.

XVI Wallace, Sophie, “Same But Different Speech,” unpublished manuscript, 2012.

Tags: Journal