8.17.2012 Interview with Jongil Ma by Lisa A. Banner

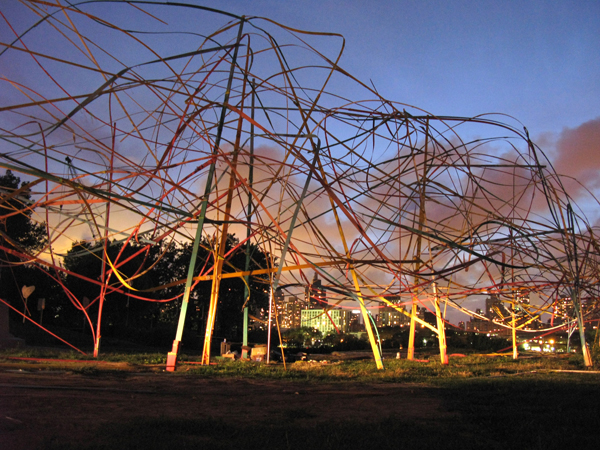

To You, Little Bigger Than A Sweet Summer Pink Peach, Socrates Sculpture Park, NY, 2008, wood, rope, paint, 30 x 150 x 30ft

Lisa A Banner: We are meeting at Grand Central Station for this interview on August 17, 2012, at 4:00 in the afternoon, with sculptor Jongil Ma, and his collaborator, painter Elizabeth Winton.

Jongil, tell us about how you came to work with wood, and what inspires you to create such large-scale works, especially those outside, in full view of everyone. Is there something in your personal background that informs the decision to be a sculptor on a grand scale? Your process intrigues me. When you first started working with wood, what prompted you to do that?

Jongil Ma: When I started in art school, it was late in my life, I was 35 when I started the first year in SVA. In my third year of art school, something hit me: that I would be finished in one more year, so I had to be realistic to survive as an artist. From that line of thinking, I was focused on what do I do better than anybody? Because NYC is full of highly skilled, professional people, you have to do something outstanding, whether you are a designer, or artist, or professional. The result of that consideration was to look at wood. I believed at that time that if I worked with wood, I could do anything I wanted, and do it better than anybody. Michelangelo was great with stone, and I felt that I could do something like that with wood. So I began to work with soft wood, and began to make some simple shapes in wood, and this impressed one of my professors, who hired me to make sculptures. After that I began to develop the skill with wood.

LAB: When did you come to the U.S. and was it for art school, or some other reason?

JM: When I came to the U.S. in 1996 it was for studying art. I had worked over 15 years since I graduated high school. I was looking for creative profession. I thought it was to become an artist. Since I was really young, I realized that I played with wood a lot. Since I was seven years old I was using hammers and chisels, and nailing things, like everyday toys, and those activities are in my body.

LAB: Like a muscle memory.

JM: Yes, it’s like when you want to be a good pianist, you have to grow up with those circumstances. A close family member plays music, or something like that, and it shapes your interests.

Tracing the Letter You Wrote, Saying ‘I Love You’, Bronx Museum, NY, 2011, wood, rope, paint, 30 x 50 x 16ft

LAB: When I first saw your work in a small shadow box, and in photographs of the monumental bent wood structures, you told me that you were creating bridges. Can you remark on that? JM: I was not literally creating bridges. I was trying to bring the feeling of these gigantic human made structures, with thousands of parts delicately balancing to hold the structure up. Those structures connect two different lands, or stand in the certain place. It is also a metaphor of human society connected through each individual to construct some group, then it becomes a physical community. I was projecting the similarity between the life and the monumental structures.

Those of bridges, in the wide-open land of the States, are not only meant of practicality but also symbolizing the human’s desire to control, or invading or challenging, struggling to the new place. It is my gesture to reproduce my own way of combining social consciousness while I am building abstraction of monuments.

LAB: Please tell us about your process, how is the wood prepared for your sculptures, what kind of wood do you use, and how is it bound together? Is the material that binds the wood important in creating the tension that seems to create balance and resistance in your work?

JM: For indoor works I use mostly fine wood, such as maple, oak. I use bamboo, poplar and pine for outdoor projects. I separate wood or bamboo for structural or detail use. Those of structural wood or bamboo will be mostly straight or slightly curved so usually thicker. I cut wood or split bamboo into various thin strips to use for details. The thickness will have different ranges; depends on the size of piece. For small scale indoor projects some strips can be from paper-thin to ½” thick or thicker. The right thickness will be showing the right amount of curve line with the right amount of tension. After I prepare all the different amounts of material I separate them into some groups for coloring along with some adequate amount of ropes too. When all the material is ready, of course I move it to the space. Usually I feel overwhelmed in the space.

Although I have some plan before starting, the large empty space is challenging to begin with. Dividing the space to have the right balance and filling the space with delicate tension are always the basis of the installation along with each physical structures’ own balance and tension. From the beginning, for every step I am aware that I am a performer in the open space stage. Each moment when I step forward I am using my whole life experience through the performance.

No One Could See Me, But I Could Hear Everything, Damyang, Korea, 2007, bamboo, rope, paint, 300 x 300 x 27ft

LAB: The first work I saw of yours, in person, was in a Korean art gallery in Queens. There was a giant tree installation that scraped the ceiling and the floor, but had no roots. The branches were cut, truncated, and the bark was painted in stripes of beautiful color, running vertically down the trunk.

JM: In many cases, I feel that we are living with artificial things around us in this time and this place. People are interacting with artificial things a lot. In making the sculpture, I was influenced by that thought, and it is a simple way of echoing this time in my life. Also, that particular gallery, and the culture of that place, offered a way to reach another level of meaning. I had already created a serious installation there, two years ago. This time, I thought the work should have some inner meaning, or a kind of attraction that would make people curious. In that neighborhood, the people are not really close to that culture. So I wanted to invest in the work an essential quality to make them attracted to the work. From that thought I put lots of colors and many different thicknesses to make people attracted to the work. In a simple way I can say, although it may not be appropriate to say, it was like bait for a fish, or like a flower attracting bees and butterflies. It is really difficult when I think about the audience. I feel connected to the audience’s response. I am a social being, and without somehow exchanging or communicating with people it feels meaningless.

LAB: That’s quite profound, simply said, and very moving. What you imply is that there is a reaction that becomes part of the work, and that you as an artist are responding to something, anticipating something as you make that work to appeal to the viewer. Let’s talk about an outdoor installation that you made for the Socrates Sculpture Park. Some of the installation shots for the Socrates Sculpture Park were really amazing, would you talk about the outdoor installation there?

JM: That installation was influenced by modern monumental architectural projects, like bridges, airports, and sports complexes. These structures have all these instances of human relationship. The way they associate with humans is in the structure and the composition. There are big columns and sub-columns. It is about tension between the structures, which I have emotionally felt in situations in urban life. There is a lot of tension in this city life. And I observe that other people feel the same thing.

Borrowing the form of the architectural structure, mixed with my feelings and the experience that I have in this city, I created a sculpture installation that reflected all those components. My piece is composed of very thin lines, weaving in the air. It isn’t a really strong structure, it is just very fragile, but it doesn’t collapse easily. It is like our delicate feeling of human interaction. Specifically I focused on people here in New York City. People in different regions have different tensions, and different aspects to their social life. All the sculptures I’m doing are about contemporary people interacting. So I tried to grab that when I was building the piece in Socrates Sculpture Park, and infuse the piece with that feeling.

LAB: You’ve installed sculptures in several boroughs of NYC. Do you perceive differences in the tensions you describe in different areas of NYC?

JM: Yes, people in Brooklyn, Staten Island, Islip, all have a different quality of life. And of course I’m doing this work at different times. So I move around from different aspects, from previous traditions to a new situation. It really influenced my way of making the art piece.

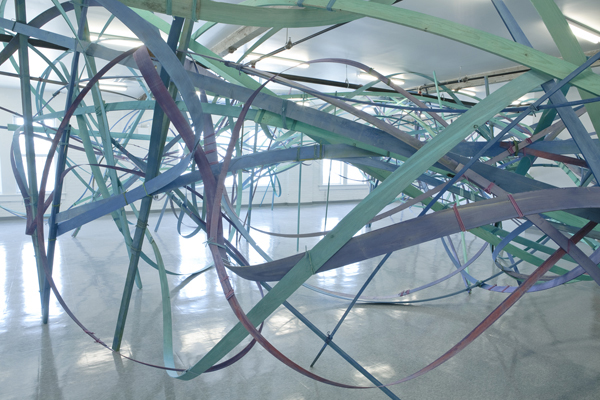

Yes, Honey, You Can Bounce Back And Forth, And You Are A Bit Closer To It,

Governors Island, New York, 2010, wood, rope, paint, 45 x 45 x 12ft

LAB: So the work is interactive, reflective and responsive to the situation. At the core, it is human. JM: Yes. My work responds to the geography of the situation, and my psychology is responding to the time in which I’m making the work. Maybe everybody does, but an artist is looking for something and developing an idea, changing his or her mind, and responding to the environment. This is why, most artists toward the end of their life complete their work in a stable or more perfect way, processing their psychology with insight.

LAB: Is that true for everyone?

JM: Really. Every day I feel something different and change my perspective. Every day I am thinking and re-thinking, trying to find something different, to make progress, to find more perfection. I think it is true for every artist that I see, like Eli, or others. Essentially they try to find a new idea, a more perfect world. And to improve the quality of life for everyone.

LAB: Sculpture does improve our quality of life, because it invites both a visual exploration and an exploration of space in relation to ourselves. How does your work respond to that particular exploration?

JM: That is a good question. A collector I know, who is a big supporter of artists, wants to support only three-dimensional sculptors because sculpture has a lot more tangible qualities. It allows one to observe multiple points more than two-dimensional work and that’s why all these young kids love three-dimensional figures more than two-dimensional images. He believes eventually that three-dimensional art will be pervasive in every society. So to me, it is very interesting, because when I started drawing… in Korea they do a lot of practicing of drawing, like copying sculptures with a pencil drawing, so you have to see the three-dimensional aspect of the object to bring it into space. I was really bad at that. So the teacher told me that after I started making sculpture pieces, I started to be fascinated with three-dimensional sculpture pieces. Because basically what I am doing is dividing this three-dimensional space as I want it. And before I started to do that, the space is nothing. But for example, in the Socrates Sculpture Park, I made huge columns, and between them I put single lines flowing from one to the other. It made the space different. It is a stunning pleasure to do it. From there I started dividing it all different ways. Certain parts are dense and some are loose, tightness and looseness. That part is basically like painting or drawing in space. Which is a lot bigger action. A serious component of the space. People see the result, but I often think about the whole process in the space. The process is the form of the work. Cutting all the pieces and putting it together. Sometimes it is really dangerous, because I’m working 30 feet high, or using heavy materials, in a high space, so all this activity is part of the work, which makes me very excited. Excited to do it.

LAB: You received a Pollack/Krasner award, was that for a specific project, or did a specific project emerge from that?

JM: It was a general support award, so I will make something for an upcoming group show, and maintain my studio space, and buy tools to make the art pieces.

LAB: A work you did for the Bronx Museum has a beautiful and evocative title, as do all of your works, sort of tongue-in-cheek, and provocative. They bring up multiple associations. But can you say something about “Tracing the Letter You Wrote Saying, ‘I Love You.’”?

Yes, Honey, You Can Bounce Back And Forth, And You Are A Bit Closer To It,

Governors Island, New York, 2010, wood, rope, paint, 45 x 45 x 12ft

JM: I think you are right. It obviously has multiple associations. I am trying constantly to understand people’s behavior in this city. I get the information from all different resources, such as newspaper, Internet, friends, my own observation and so on. Then I process it my own way for the project. Of course I intend multiple perspectives. However the idea processed while I am planning a project will be the main theme. I choose colors, I design the form of installation with the theme. On the other hand, I personally have been very interested in certain lyrics appearing in rock and roll music. Some of the lyrics have incredible authenticity and reality about our individual life relationship. It is such beauty and I work with it. Finally the title contains a feeling of loss. It tries to retreat the feeling.

LAB: One installation you did in Korea intruded into the physical space of a building, and was formed of orange, red, yellow and green bent wood. Was that, “You Have To Run, Don’t Look Back.”? Could you comment on the title and its relation to the experience of creating that piece?

JM: The title was very much related with my own situation. I had been working for some artists and I had a serious issue with them. It was a moment whether I continue my type of installation or not. And also I made this title because it does connect to everybody’s life in general. Our life can be said to make a decisions. Many times you cannot proceed easily because of all the different types of obstacles. Especially in Korea now, with the extra amount of speed of development, people quickly lose their integrity. So, this title not only says what you are supposed to do but it is also being cynical.

LAB: A second installation in Korea, in 2007, was poignantly entitled: “No One Could See Me, But I Could Hear Everything.” Was this about an experience in Korea, or in New York, or did the concept evolve from another experience?

JM: This feeling was absolutely mixed both in Korea and New York. In general, people, including myself, constantly try to grab something they need. This is more likely associated with domination. Life before I started to create artworks and after, it is feeling about the individual, me and other.

LAB: On Governor’s Island you made an indoor installation that is poetically held within a room, and is composed of wood painted in a cooler palette, of blues, purples and greens. Was there a connection between the harmony of the colors you chose, and the type of expression you were after within the bent wood?

JM: The color was chosen by the water around the gallery location and the audience I was expecting during the particular season. This was a kind of public project although it was an indoor space. I also meant to emphasize the whole piece by using monotones. It was also some kind of mind road map.

LAB: I’m also interested in the project you did for the LAB Gallery in the 30s, here in NYC.

JM: This was the fourth indoor piece that I did, combining two-dimensional drawings and sculpture. So the installation itself was abstract, and I wanted to give it a more solid idea by combining that with drawings. The drawings I enlarged.. like an illustrated book, like wolves, one endless snowy field in Canada, or somewhere, full of snow. And they condemned one of the wolves in the pack. One got hurt, and died in the plain snowy land. The rest of the family, the pack of wolves, were sitting and watching in a circle around the one who died. You can see the footsteps connected to the victim. I blew up this one image, and made my own drawings. I blew them up to 10 feet by 37 with a green background, and I added green, with a circle of a target mark, near the victim’s area. So in this installation I tried to connect ideas of this image and the installation.

LAB: Where did you put the drawings?

JM: On the back wall of the exhibition, near the target mark, one wolf face stares at the viewer. It was the background for the entire installation.

LAB: Do you often use drawings in your work, or is that something unusual?

JM: This was the third case, and I will do a lot more in the future. The first time it was of a simple line drawing of an abandoned house drawing in Korea. A simple rainbow color striped drawing, connecting room to room and space to space.

Hello There, Walking Away From It Ain’t No Fun, Randall’s Island, NY, 2011,

wood, rope, paint, 30x 60 x 20ft

LAB: What do the rainbow colors signify?

JM: At that time I was thinking about the sense of essence of life, being. An empty abandoned house. I tried to recreate the space with a sense of life.

LAB: Reanimate?

JM: Yes. The people are obviously not there. It was like a housing project in the area. The government was waiting for the space. And obviously government was trying to help the poor people, but I wasn’t sure whether it was a good idea. So I was thinking about all this. Something pure, placing a likeness of the human life there. It was a public project. I couldn’t think about only the artist inside. I had to respond to the public project.

LAB: Describe some other projects that you’ve completed in the last two years.

JM: Bronx Museum, Randall’s Island, Islip, a project in Korea. I also did a collaboration with Elizabeth Winton. [He smiles and gestures to Eli, sitting with us.]

Elizabeth Winton: [She laughs] Originally it was his project and then we wanted to collaborate. We had to work off of Jong’s original proposal ideas. We were working in a way that was much less abstract for us both. Once we asked the gallery about my participation and they said yes, we dove in together. I think we had only about 10 days to work?

JM: It involved figurative sculpture pieces like beetles, and two-dimensional drawing.

LAB: Beetles?

EW: We were interested in a sort of storybook illustration quality with oversized beetles wandering down a path. We had had a conversation about a year before just walking down the street. He and I are always working. We were walking in the shade and passed this bar. He asked what was the word in English for shade and this conversation became this piece.

LAB: Where was this?

EW: The LAB Gallery. It was a storefront gallery in midtown. Kind of a fishbowl. You have to catch people’s eye quickly. So the first challenge was how to build the beetles. We bought all this crazy spandex and sequined fabric. We hired a Japanese clothing designer to sew the spandex to cover three of the beetles. Two of them I painted. They were loosely based on real beetles. I called up my cousin who is an entomologist to learn more about beetle behavior and biology. In our piece they were having a dinner party.

JM: It is a satire of city people.

EW: Yeah beetles can be beautiful, brilliant colors changing in the light. Functionally their shiny exoskeleton provides both armor and flexibility. Some are predators but then also are prey. Really the most direct and rewarding part was that little kids would climb out of their strollers to get a better view while their parents tried to hurry past not noticing our corner until after.

LAB: This was one of only 2 indoor installations so far?

To You, Little Bigger Than A Sweet Summer Pink Peach, Socrates Sculpture Park, NY, 2008,

wood, rope, paint, 30 x 150 x 30ft

JM: I have done many indoor installations, nearly as many as outdoor.

LAB: Do you prefer to be outside?

JM: Bronx Museum and Islip were both inside. It is important to me to do both.

LAB: What is the next project you imagine?

JM: My next project will likely be indoors. It will have a pictorial aspect rather than just linear abstractions. I’m moving toward more figurative work, and also trying to grab irony. Also in the past I looked at social or political relationships. But in the future I want to create what I can actually express. Social and political aspects of life.

LAB: To make figurative work seems like a radical departure from what you’ve been doing with bent and twisted wood structures under tension, tied together with small thin ribbons, ropes and twine.

JM: After doing these installations I realize that I have to be sharper than what I have been. It is a really difficult thing, but I want to grab a more efficient quality of the work, more like condensed contemporary ideas. It will be a long-time process, but I believe that this is what artists are supposed to do in any society… to respond with an expression about the social political circumstances. Engage more directly with it.

LAB: Your work seems fully realized, and fully engaged, and evolving in response to the circumstances. It is such a great pleasure to speak with you today. Thank you, Jongil and Eli.

Jongil Ma is a Korean artist who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He received his BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 2002. He has had solo and collaborative exhibitions at The Lab Gallery at the Roger Smith Hotel in Manhattan, “Jamaica Flux: Workspaces & Windows” at Jamaica Center For Arts & Learning in Queens, and the LMCC Governors Island Project in 2010. His work has been featured in international exhibitions including the 2009 International Incheon Women Artist’s Biennale in Korea and the Lodz Biennale in Poland in 2010. In 2011 he participated in the AIM Bienial Exhibition in the Bronx Museum, a Group Exhibition in the Islip Art Museum, and created a piece at the Randall’s Island Park in conjunction with “FLOW.11: Art and Music at Randall’s Island.” His awards include the INC Visual Arts Award from the AHL Foundation, a Fellowship from Socrates Sculpture Park and Award, and a grant from Pollock Krasner in 2012.

Elizabeth Winton is Brooklyn-based visual artist, working primarily with paint and mixed media on paper, wood, and canvas. She received a BA from Connecticut College. She has exhibited her work throughout the United States and Asia, including shows at the Lower East Side Printshop, New York; Metro Gallery, Gwanju, Korea; Kolok Gallery, North Adams, MA; Margaret Bodell Gallery, New York; and a solo show at Ruby Green Contemporary Art Center in Nashville, TN. Her most recent solo exhibition, curated by Douglas Dunn, was at CUE Art Foundation in New York in 2011, followed by a collaborative installation project at the LAB Gallery at the Roger Smith Hotel in Manhattan, and a group exhibition at Brooklyn Fire Proof in 2012.

Tags: Journal