Feature: Looking at the work of Jude Broughan through the eye of Arthur Dove’s needle by Meaghan Kent

The history of collage and its connections to New York City are manifold. In a city where you can find just about anything you want, whenever you want, making mixed media objects would be ideal. Moreover, the political and cultural issues circulating throughout the metropolis present the collage as a unique paradox between man and machine. Modernity in the urban environment can ignite inspiration.

Arthur Dove’s “Hand Sewing Machine” (1927) was influenced by and reacting to New York City’s industrial movement. The dynamic collage would seem atypical of his work; Dove is known primarily for his abstractions where the intention was to shift from materialism and concentrate more on nature. He had a close friendship with artist and dealer Alfred Stieglitz and both “shared a critical attitude toward the materialism of American life and a belief that the conventional art of their time was inadequate to the expression of contemporary values.” (I)

Arthur Dove, Hand Sewing Machine, 1927, Oil, cut and pasted linen, resin, and graphite on

sheet metal, with artist made frame, 14 x 19.75in, courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

While showing his work at Stieglitz’s galleries, Dove worked on and off as an illustrator in New York City. He would leave the city several times in his lifetime; first to Europe in 1907, next to the suburbs of Westport, Connecticut with his first wife in 1909, and then in 1920 to a houseboat on the Harlem River (and later Long Island) with his second wife, painter Helen Torr. (II) Leaving the city proper, he sought nature; which led him to non-representational work that he coined as extraction. (III)

On his boat, he made 25 known collages. (IV) The use of material was both critical and playful. In a sense, he was still extracting; but this time, he was reinterpreting found objects and materials. He was using everyday items: sandpaper, tape measures, cardboard, wood, and making them become something else. In many cases these paintings were made as portraits of friends and neighbors, symbolic attributes with humorous undertones. (V)

“Hand Sewing Machine” is a reflection of a mass produced object that replaces the individual craft. The whirl and painterly brushstroke in the upper right corner of the painting reads like the pulse of the speed of a locomotive. On the left side, the crank on the handle of the machine almost completely disappears into the background. The play off the title “Hand Sewing Machine” nods to the human interaction with technology and modernity. Industrial materials including linen, resin, and graphite on sheet metal (aluminum) are brought together in a tongue-in-cheek fashion. The power of the piece is indicative of the influx of industrialization and most likely the growth of the garment district (only a few blocks north of Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery and southwest of The Intimate Gallery). To give further context: this is also the same year that Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” opens in Germany. The uncontrollable force of post-industrialism was realized and openly critiqued.

Dove was influenced by Cubism as a result of his travels through Europe and his friendship with Stieglitz. Through his relationship with Stieglitz, he met artists in New York City working with mixed media, including Duchamp, who had just completed “The Large Glass” in 1925. He was also around the avant-garde portraiture by Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth and well aware of the American folk art revival. (VI)

The extensive history of collage is widely varied. For Dove, collage and mixed media artwork were something with which he was not unfamiliar but were instead something he wanted to utilize. Through the use of the everyday object, Dove was able to create a narrative that appreciates the traditions of folk art and realizes the dangerous potential of the machine. Paul Thek, Al Hansen and Robert Rauschenberg (all artists living in New York for periods of time) would later use collage, or Assemblage, to emphasize the use of the printed word in modern society, to react against traditional painting, or to serve as props or studies for their performative actions in the 1960s.

As technology shifted from machine making to digital work, the use of collage has had similar effects, almost a hundred years later. Works are most often fabricated and made by machines – almost completely losing their tactile qualities in favor of a highly finished output.

In many ways, Jude Broughan’s work embraces the mechanics as a means of recognizing the excessiveness of digital images and utilizing the power, repetition, and consistency found in machinery. Broughan, born in New Zealand and living in Brooklyn, creates wall-based work that shifts from two to three-dimensionality. Broughan’s inspired use of digital prints with natural and synthetic materials works off the environment around her.

For Broughan:

(My work) embodies my immediate experience of the environment of New York, the concrete and human jungle. My palette shifts from the greys and greens of the city’s buildings and trees to hues that evoke the light of other climates—the minty green of New Zealand’s state houses or the glow of southern hemisphere sunshine through orange curtains—locating myself through a process of understanding one place, one time (and, by extension, one state of being) through allusion to countless alternatives. (VII)

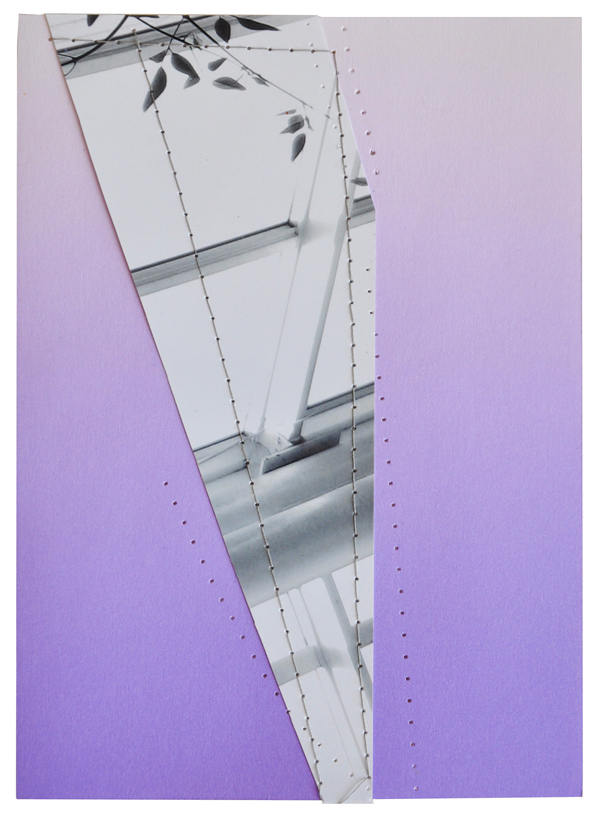

“Untitled,” 2012 juxtaposes a black and white print that has been cut in a jagged shape and stitched to lavender colored paper. The cool solid color against the image of light creates a contrast of positive and negative space. The jagged shape of the print in “Untitled” becomes pure form and has a similar sensibility to the linen fabric in Dove’s “Hand Sewing Machine.” Both shapes aim downward through the middle of the picture plane and spill off of the canvas. The framing of the irregular shape in “Untitled” is reiterated with the stitching across the paper and print as if to mimic the irregularity of lines in the image itself. The process of sewing, a monotonous repetition, becomes part of the picture and creates its own forms and patterns with the punched holes and lines.

Broughan culls images from various sources including vintage cookbooks, gardening and library books, or her own photography ranging from her daily routines to traveling.

There are themes that run throughout recent projects, one of the most important being a critique of the role of photography as a visual dialect associated with commercial culture. The images I produce are openly flawed and ambiguous, so that viewers anticipating the seductive surface of conventional ‘high-end’ photography might feel stymied at first. Displacing the promise of closure is a palpable tension between private and public, between ‘full’ and seemingly empty space.

“Bookcase” is a juxtaposition of an interior setting intertwined in folds of vinyl fabric and plastic Broughan had acquired in Chinatown. The books on the shelves suggest current perspectives on printed materials as everything now shifts to the digital era. The image itself reveals the marks of the scan and becomes even more blurred under a filtered shard of plastic. Broughan has worked with collage for several years, she writes:

I have always used elements of collage, if not always in finished works, then in sketchbooks and experiments. Recently, vinyl and plastics have been my main ‘fabrics’; they really push the sewing machine to its limit.

Broughan’s work is a hybrid of approaches that shifts from machine to handmade and back again. Much like in Dove’s title and painting – the “hand” element comes into play by operating machinery to create the object but disappears in the final output.

In general, my work combines the languages of photography, painting, printmaking, and collage. I juxtapose photographic prints with physically constructed elements, aiming to achieve a feeling of immediacy and provide different points of access for the viewer. The results are presented as intimate improvised conversations around perceptions of the quotidian.

With collage, there is an idea of placing the materials and objects to create a cohesive piece. The feeling of intimacy in Broughan’s work can be attributed to her choice in imagery and the domesticity of the personal sewing machine. There is a flow with the punctured marks, layers, and textures in Broughan’s work, a kind of poetry in the rhythm of the machine.

Jude Broughan is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. See contributors section. judebroughan.com

I Morgan, Ann Lee, Arthur Dove: His Life and Work with a Catalogue Raisonne (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1984)

II The Phillips Collection, The Eye of Duncan Phillips, Yale University Press, 1999, 398

III Morgan, Ann Lee, Arthur Dove: His Life and Work with a Catalogue Raisonne (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1984)

IV Phillips Collection, “Huntington Harbor I, 1926,” phillipscollection.org/research/american_art/artwork/Dove-Huntington_HarborI.htm

V Metropolitan Museum, “Portrait of Ralph Dusenberry,” metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/49.70.36

VI Phillips Collection, “Huntington Harbor I, 1926,” phillipscollection.org/research/american_art/artwork/Dove-Huntington_HarborI.htm

VII All indented quotes are from an email interview with Jude Broughan, September 5, 2012

Additional Sources:

Todd, Emily Leland, “Pieces of Experience Literally Seized: Arthur Dove’s Symbolic Portraits in Collage, 1924-25,” Rice University, 1988

Wilson, Kristina, “The Intimate Gallery and the Equivalents: Spirituality in the 1920s Work of Stieglitz,” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 85, No.4, December 2003,

746-768.