1.9.13 The Possibility of Colloquial Aesthetics in Miami: A Three-Way Discussion with Aramis Gutierrez, Loriel Beltran and Domingo Castillo

Aramis Gutierrez: I want to start this discussion by asking if you think that a colloquial aesthetic can develop here in Miami? The biggest Post-Cuban thing that happened here is what happened in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. Artists like Hernan Bas, Naomi Fisher, Luis Gispert and a lot of other people here really found a voice, but as of lately it is difficult to say if that work has pollinated [into] something unified, or even if it is gestating into something else recognizable. When I think of the work from that moment, I remember there was a predominant sense tropicality going on.

Domingo Castillo: It’s funny you bring up tropicality. There was certainly a ‘savage’ aesthetic, but there were also architectural themes that were coming up in a lot of people’s works, probably from all the construction cranes that popped up in the mid-2000s. Diego Singh seems to have capitalized on something very Miami in his denim paintings. Denim has its own vernacular in Miami that is especially prominent in South Beach and with the various South American groups pouring in.

AG: Because Miami is such a transient international city, I always wonder if that works against the possibility of forming a colloquial aesthetic or myth. Besides the locals, we have these three major economies that feed into our city. We have Europeans, who come here to vacation; the seasonal northeasterners, who come to escape the winter and taxes; and the South Americans, who come here for a stable environment for their investments. Each has its own school of thought and culture. I always find that most of the Miami-based culture I am interested in is from the local culture, from the people who were born here or have just ended up living here year-round.

Loriel Beltran: Art may be high culture but it is always informed by low culture. If you are in contact with all these people, their culture affects you. I don’t think it is so much a choice as much as what you encounter on a daily basis. Either it becomes part of your work naturally or you try to make work that is conscious of it.

AG: I know from painting in Miami, that part of me has tried to find this moment that allows me to convey the light, the color and the transient nature of this place. I felt that coming from New York and being educated there meant I was at odds with it. So I came up with tricks to outthink or derail my limitations, like setting up my palette. I am no longer a tourist, but I will always be somewhat of an outsider looking in.

LB: Everybody is.

DC: Everyone is. All the information you are getting is coming from outside anyway. So if you are accessing that information, you are automatically becoming “outside.” You are removing yourself from site and place. It makes us different from New York or L.A. because a lot of that information is right there. It’s being made there. If you are watching a movie in L.A., Hollywood is right there.

AG: That’s a funny point. Whenever you see Miami depicted on film, it is never really accurate.

DC: Miami Vice in the ‘80s was crazy. It looked like there was a party here, and there was tons of crime, but there was a lot more going on.

AG: If one is looking for an aesthetic in Miami, they might turn to our galleries. Lately when you look at the majority of galleries in America, it is easy to get a feel for whose roster is N.Y. or L.A. -centric, but there doesn’t seem to be a gallery that sums up what is going on in Miami. Maybe it is too much to ask at this point.

DC: That’s because there aren’t enough artists here, or not enough that are that critical or that have some kind of position. We need enough artists to be in multiple galleries, moving in different engaged circles, so you could get a better understanding of what’s going on here.

AG: But let’s back up. N.Y. and L.A. also have these graduate programs in place. They homogenize and streamline the paradigms these artists are thinking about. In comparison, work coming from artists in Miami is all over the place.

DC: What I love about Miami is that there is no reason to historicize anything. People here just don’t give a shit. So things don’t permutate in an academic environment, where events are organized, and they say this is what happened here over the last ten years. A lot of these schools are in place to look at the recent afterthought more than anything else. Here you don’t have that. A lot of places and projects don’t become institutionalized. In this way, it is a lot richer artistically because there are no institutions to conform to, and at the same time, it doesn’t allow people to know what came before, so there is this constant feeling of the new and that things are about to go crazy.

AG: It’s funny, when I first moved to Miami, and sadly this has gotten less and less exciting the longer I’ve lived here, I was very pleased that the artists here were doing their own thing. Nobody was really looking over each other’s shoulders to inform their work, and people were just operating on their own and finding something they wanted to do, and going for it. Coming from New York, this was really refreshing to see. I remember I got into a debate about it with a friend, that this kind of richness would be lost if grad programs were put in place. At the same time, six years on, my friend is now winning the argument. A lot of artists are moving away from Miami and I am seeing less and less new young faces. What is worse is that Miami has always had a reputation for superficiality and that is what’s sticking. It has always gotten more attention than our cultural output. Do you feel that superficiality has a negative connotation here in Miami? Does it always have to?

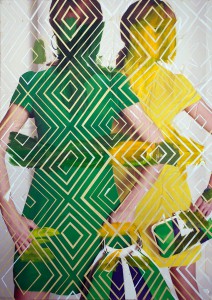

LB: Yes, but I am trying to embrace it. I wanted to go back to painting but I didn’t know where to start. That’s why I went back to advertising, because they are the only images being generated here and solidly reinforcing an aesthetic.

AG: When I am starting a new body of paintings, I always go back to the last thing I trust, which are different things at different times. Why did you choose advertising?

LB: In bus stop advertisements, you have these crystalline islands of aesthetics presented for you in the concrete jungle. Fashion is one of the only industries really generating any kind of cohesive imagery in Miami that is coherent enough to have a dialogue with.

DC: Thinking about superficiality and fashion can be really nice; they have the tendency to shamelessly generate aesthetic in an instant.

AG: I think painting has a temporal duality in how you experience it. Initially, you have that first instant to dismiss it. In most cases, rejection is exactly what happens. However, sometimes there is an instant attraction, when something grabs your attention and can’t be ignored. It’s similar to window-shopping, which makes me think about how you are pushing this exchange by using advertising in your paintings.

DC: Also, half the work is done for you.

LB: Yes, but once you paint on advertisements, it’s promoting the aesthetic and it’s the thing itself. Instead of being relevant for a season, maybe it will become universal.

DC: It works because you abstract the sale. When they were selling swampland in the ‘20s, everything depended on advertisement to conceptualize the potential.

AG: Now some of these new condos are just so sexy that during the sale you overlook that they lack any closets. Similarly, your paintings remove the subconscious product. Suddenly that expensive watch isn’t there and what you’re left with is the pure abstract gratification of being set up for the sale.

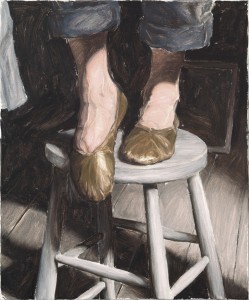

DC: One of the reasons I came back to Miami to live and work is that New York forces abstraction. This is because you are completely removed from your situation and that becomes the situation. The things you are left with are the aesthetic situations that happen in abstraction. Coming back here I wanted to become more in tune with the reality of Miami. So I started painting, but I only want to make paintings that could be shown in furniture stores. Painting is the only medium that can never remove itself from the art conversation. Sometimes sculpture, video and photography can be broken down into their source materials. Painting, on the other hand, can never just be material. It will always be considered art. Because of this, generic painting becomes the equivalent of open source. It is a visual cue that represents…something. That self-awareness is something I pay attention to. Once you are self aware, it gives you the freedom to speak. Then you can start speaking about all these systems and how things function within them. It also opens these in-betweens, like subjectivity and objectivity, in doing these actions.

AG: Because there are so many different cultures converging here, and we as artists are looking in from the outside, many of the visual cues, for all their subtlety, appear obvious. If you are sensitive to it, these cues appear humorous because they are so simple and direct. Here is the cue and here is the sale. For some reason, El Dorado furniture store just came to mind. Maybe it is a good example of this.

LB: They have the boulevard.

DC: They have the boulevard! The whole thing is a set-up. It’s better than IKEA because they have everything. It’s not just for the Bauhaus-oriented. It personalized and it’s not removed.

AG: It’s more exclusive. Whatever you are looking for, they have it and it’s affordable. Maybe we are comfortable with their hodgepodge because we all come from a Latin American background. It might be too pluralist for European or Caucasian sensibilities, whereas we are kind of used to the mess and assimilating everything. I remember in Venezuela, my family purchased a white minimalist painting and hung it in their predominantly Caraqueño-styled living room. They were very proud of it and loved to show it off as being expensive and eccentric, but once the stigma wore off it became like all their other paintings of pueblos and cows in pastures. It became just another visual cue.

DC: Kind of, though, because abstraction developed its own language in South America for such a long time. It isn’t another cow painting. It’s an abstract painting, that’s the “painting” you need in your house.

AG: I often think about how Modernism never left the conversation in South American art. In Venezuela, Op art is alive and well. Modernist formalism has recently re-entered the conversation in Western Contemporary art, but it is not taken in complete earnest. In South America, it is sacrosanct. They’re still doing it because they never stopped doing it. When you see this art in Miami, it becomes part of our colloquial perspective. It’s in this grey area. You don’t have to embrace it, but you consider it.

DC: Yeah, because you are seeing everything. You are walking into different houses and malls and you are seeing all these situations and possibilities. You are navigating all these weird contrasted spaces.

LB: When you are in people’s houses, they all bring as much of their culture as they can. It dilutes into this in-between, which is eclectic. Nothing is unified. It is a mess, but it is a nice mess. It keeps things interesting.

DC: No one is fully assimilating towards one thing, but you assimilate to what you gravitate towards. Everyone is gravitating towards three different things at once and all of these different cues are coming together to create a unique identity.

AG: I know this is cliché, but I am obsessed with the light in Miami. I am always trying to organize my work so this light makes sense within the context of the image.

LB: Coming from Caracas, we have El Avila. Nature is present and it is a beautiful feature of that city. Miami has light, but it is elusive and everything seems to slip through the cracks.

AG: I have this German friend who gets depressed in the summertime because the light in Miami becomes so oppressive. It’s different somehow. It’s right above you and it’s on you all day, but the rest of the year, after summer, you get into this hedonistic relationship with the sky and the light. I have gone to great lengths to make sure my living quarters has a view of the sky. After some consideration I have even arranged my palette to consider this. I can paint whatever, but I am using these colors and thinking this way. I had Nick Lobo over at the studio recently and he mentioned that I am making very colloquial paintings, which is pleasing because the only cue that would communicate this would be the light. It isn’t conceptually engrained in the image but symptomatic of how I am making the work.

LB: It’s really funny that they look like Florida paintings.

DC: It’s the subversive atmosphere that is created by those colors and the light that you can’t be fully aware of, but you can feel it.

AG: The handling also outsets the light so that it becomes subversive. Tom McGrath once told me that my handling is scatological. When you compound that with light, it creates the possibility for contradiction, where something is grotesque and beautiful at the same time. I remember hearing that a lot of people in the early twentieth century thought the Everglades were ugly. This has long been the argument for paving over the swamps and developing them. If you remove something’s value, then annihilation is the proper thing to do. At some point there was a conservationist backlash. The argument arose that this habitat is in fact beautiful and people just weren’t considering their unique aesthetic. This predicament is anthemic to Florida; there is value here and people just don’t get it. How then do we imbue our culture with value so people will appreciate and respect it? This is why I am always thinking about the colloquial value of work I see here, because this is the key to what makes us special.

LB: The most important part of being colloquial is that it is real, it’s happening, and something is backing it up.

AG: Loro, you once said something I really agree with but I never really considered. You said you were more interested in seeing what artists in Miami are doing, rather than going on blogs or seeing artwork from the outside. Even going to someone’s studio here is a lot more interesting than being in New York, where everyone is breathing the same air.

LB: What you do every day is what you really are. That’s the way that the best art can happen and why I am interested in seeing what is going on here in Miami, because it’s part of my reality. It is in tune with who I really am, not who I want to be. Whether I like it or not, it is closer to who I am. I know the situation here isn’t easy for art to develop because we lack institutions and structure. I appreciate having the time, and I see people stepping up and learning on their own. This is why I think there is the opportunity for something good to happen here.

AG: It is a contiguous tabula rasa here. There are so many new cultures constantly pouring in from other places. In addition, you have new naturalized culture- participants whose descendants were displaced and are no longer in touch with their traditional cultural heritage. They were told about their culture, but they never experienced it first hand and have since moved on. This is a real opportunity and why I believe it is important for us to focus on new aesthetics instead of trying to seek validation through mimicry. Perhaps we don’t need another curator to come here from some out-of-state grad program, trying to find commonalities to compare with the art world at-large. Is it acceptable for someone trained in New York and L.A. to interpret our culture?

DC: They are also tourists. Even if they approach the excess of this place, they never fully appreciate what is going on here. They leave and say this place was unintelligible.

AG: I’m not trying to be dismissive about the academia already here, but as artists, is it our responsibility to form these people? Should we demand it?

LB: They have to spend enough time. We have good people who recently moved here who seem like they are interested in this place for what it is and want to make it work. I’m thinking of Diana Nawi and Amanda Sanfilippo, for example. And then we have people like Gean Moreno and Rene Morales that have always been about it. Maybe the validation of going to a respected grad program isn’t what is needed, but the time and the quality of what you do while you’re here.

DC: There is no syringe that pumps you or this city with information. You have to be here long enough to figure everything out for yourself.

AG: Someone has to really look at this and come to terms with how artists working here fit within our dynamic culture. The artwork here can have a common thread, but we are all coming from such different places. Maybe we need a sociologist.

Aramis Gutierrez was born in 1975 in Pittsburgh, PA of Venezuelan, Slavic and Scottish decent. He received a BFA in painting from Cooper Union in 1998 and studied an additional 5 years in post-baccalaureate studies. The artist has shown in New York, Philadelphia, Palm Beach, Miami, Istanbul, and was part of the Studio Residency Program at the Deering Estate at Cutler. Most recently he has exhibited at the Miami Museum of Art. Gutierrez currently lives and works in Little Haiti, Miami. spinelloprojects.com

Loriel Beltran was born in Caracas, Venezuela in 1985. At age fifteen, he moved to Miami where he obtained a BFA from New World School of the Arts in Electronic Intermedia. Beltran has exhibited at the Wolfsonian Museum’s Bridge Tenders House in Miami Beach, and has been part of group exhibitions at The Miami Art Museum, The Museo de Arte Acarigua Araure in Acarigua, Venezuela, The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. Solo exhibitions include Fredric Snitzer Gallery and Locust Projects, both in Miami.lorielbeltran.com

Mr. Castillo has unrivaled experience and expertise. He has been practicing fine art for over 50 years, advising some the most noteworthy companies in the Dominican Republic and nearly all the major corporations in Latin America. He is currently a member of the board of the main bank in the Dominican Republic. Mr. Castillo leverages his thorough understanding of the commercial and financial landscape on behalf of all the firm’s clients, advising collectors and artists on long-term strategies and crisis management.

His practice includes advising on corporate and commercial issues, mergers and acquisitions, finance and Foreign Investment across a range of industries and sectors. His extensive experience includes both non-contentious and contentious matters, advising on litigation, arbitration and mediation. In addition to advising clients, Mr. Castillo is also a prominent and active member of several boards of directors and administrative councils and holds senior positions on a number of committees.

He is also highly committed to pro bono work, as a member of the board of the Sur Futuro Foundation and the Perelló Foundation, private non-profit organizations that promote the well-being of communities in the southern region of the Dominican Republic. Mr.Castillo is also a board member and Treasurer of the Instituto Nacional de la Diabetes. In recognition of Mr. Castillo’s contribution to the Dominican Republic, he has been honored by the President with the Duarte, Sánchez and Mella Order of Merit, Gran Cruz Silver Plaque. This is the highest distinction that can be awarded by the Government of the Dominican Republic.

Beltran, Castillo, and Gutierrez will open “Guccivuitton” in Little Haiti, Miami in 2013.

Tags: Journal