Interview with Sue de Beer by Meaghan Kent 7.2.13

Meaghan Kent: So how did you connect with Westbeth, to be able to get them to loan the space?

Sue de Beer: Someone at the LMCC put me in touch with Westbeth. Their basement space was severely flooded by Hurricane Sandy. This space we are standing in used to be an archive space for the Martha Graham Dance Company. The water flooded the space up to that black line. It was devastating for their archive; everything was ruined down here.

MK: The Dance Company archives?

SdB: Yes. Westbeth emptied it out and cleaned it, but they can’t put long-term storage in here for now. I believe they are sorting out what to do with the space. It was lovely that they offered it to me for the shoot. I haven’t had the space to shoot like this since “The Quickening,” which was shot in Berlin.

I also am working with a new writer, Nathaniel Axel.

MK: In work you have made before, you wrote the text? Or were they found sources?

SdB: Alissa Bennett worked with me on a number of scripts. She worked on “Hans and Grete,” “Disappear Here,” and “The Ghosts,” amongst others. She would write monologue texts for the characters in the film, and created some beautiful, memorable lines, like: “I’m going to erase myself, and you’re going to find me everywhere.” A great depiction of suicide. I have also adapted texts from Dennis Cooper (for my film “Black Sun”) and J.K. Huysmans (“the Quickening”).

I started my collaboration with Nate with a somewhat controlled/controlling working process, where I sent him text and asked him just to re-write the language. We were getting nowhere with that method and I could see he felt trapped by the process. So I asked him to write anything—to just write a text—and gave him a length for the text. And he wrote a wild short text and that became closer to the work we have now. So he would write and I would respond to it. The script so far has links with Lovecraft and to my mind, a New England inflected version of the Occult. He has a more masculine voice that I am interested in, and the piece has become more violent, with some horror.

We ran a casting call before finishing the script, and cast a male lead that was the opposite of the character we had been developing for the film. This man disappeared from the project, and I had to replace him, but his physical presence changed the script. He was a lot older than the actress and we were going to dye his hair black and make him a seedy, marginal figure.

MK: He came in and auditioned, but he’s not actually going to be in the project?

SdB: It didn’t work out with him in the end. But the thing about having him for that short amount of time is that it changed the script. It opened up gaps in the script, made it different. Darker. Now I’m casting to replace him. I meet the last person tomorrow so we should know Monday. I start shooting on Monday as well.

MK: I had read that you often work with non-actors. Are these not professional actors?

SdB: Yes. The person that messaged me just now is a musician and I’m meeting with another musician tomorrow. I like working with musicians because they are comfortable in front of the camera. They have great faces and they’re not acting which is really what I want.

MK: And there was also a drug in the script that you mentioned earlier… Tramodol? Does it have some kind of hallucinatory effect that will be used in the project?

SdB: It’s just a prescription drug, and I’m using that as a means to not completely describe a character. No one is quite able to describe this main male character, what he looks like, or who he is. He’s the main catalyst for some…marginal activity. That’s how I would put it. I like this idea of never completing, an incomplete portrait and leaving gaps.

MK: Is it going to be along the lines of “The Ghosts”?

SdB: I think it’ll be a little faster-paced? More violent? I’m not sure; it depends on whom I get for the male character.

MK: And how long are you going to shoot for?

SdB: It’s 8 days. “The Ghosts” was shot for 8 months, a couple days here, a couple days there. Since moving back to New York, I have missed the energy that I had in Berlin, where I would go find an abandoned building and make it a part of the set. I would shoot and then leave. I would shoot in condensed periods of time so everything was lined up, everyone was trapped together on the set. I’m very proud of “The Ghosts.” It’s a project I worked on for 3 years and we shot for 8 months, which was intense. But for this project, I wanted to do something thoughtful, but fast, and to have it in a permanent state of change. It was re-writing itself each day of the shoot.

MK: And “The Ghosts” was made during the stock market crash and in Berlin (where expenses are lower than they are in New York).

SdB: I did do much of it here, too, and it was a challenge. I noticed during that time that, in general, in 2009-2010, exhibited work seemed to be smaller, more drawings, paintings. But what I’ve always done as an artist hasn’t always made sense.

MK: It’s interesting how in New York there are some limitations (such as space), but there are opportunities, like your work with musicians, and all these different kinds of people. Working with other collaborators seems to be a big factor in your work. Perhaps you can elaborate a little bit more on the process of working with some of these people? This man for instance, brings an example of how the outcome changed from the original concept through the process. Does that happen often?

SdB: Yes, every single time. In the process of shooting, the tension of the work changes with the person that I’m shooting. That is exciting to me. In a certain sense, I feel connected to the tradition of portraiture stemming from someone like Diane Arbus, or more recently Rineke Dijkstra, where the subject influences me as I work with them, and the subject defines the work in the end. But because I’m putting it in a filmic context, things like narrative or even environment get shaped partially by people that I’m working with. Part of the process is that I’m pulling things out of them. I talk with people that have strong identities of their own.

MK: I imagine that was what happened with “The Ghosts.” Since it ran over the course of 8 months, did it shift quite a bit from the original concept to the final piece?

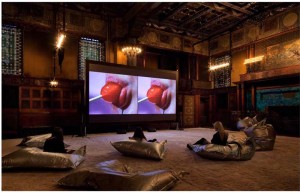

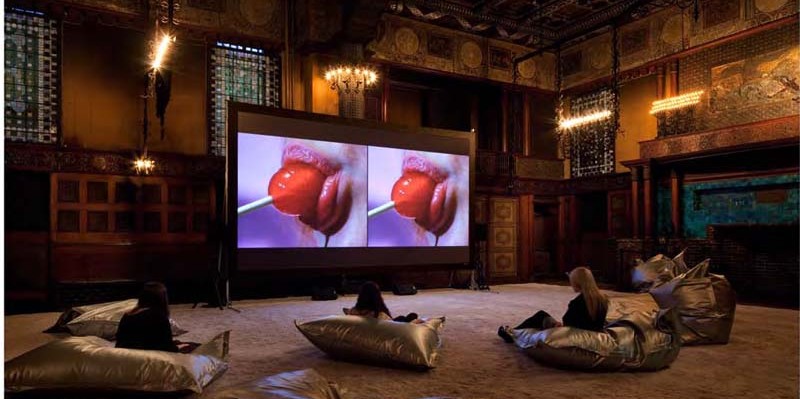

SdB: Well, “The Ghosts” more than other ones. It did shift a lot and many people involved in the project had their own strong identities and ways that they shifted the piece. The characters made their own imprint on camera and on footage, although the script was pretty complete. I wrote the whole thing before I started, and Alissa had finished the majority of the monologues, which for the most part stayed in the film. Some things changed significantly in the editing process: the hypnosis scenes, or I wrote this terrible dialogue that I cut out in favor of other pieces of footage. Like the scene with Claire and the lollipop, for example, replaced some text. But this new film is by far the most unstructured.

MK: To get back to the theme of working processes in New York, I’m curious to know the motivating factors as to what brought you to New York in the first place and if that’s something that still resonates today. If it feels accurate of why you’re still living here.

SdB: Well, I moved to New York when I was young, when I was 17. I moved here a bit by accident. I knew I wanted to be an artist but I had no idea what that meant. I went to art school here, both for undergrad and grad.

Once you’ve lived in New York, it’s hard to leave it but it’s also difficult to stay. There is an energy that comes from the street. I loved Berlin, but what I loved most about Berlin from a film-making point of view, was taking the energy of New York to Berlin and then really getting as much as I could out of Berlin, using that driven energy.

There is a cliché about Berlin around coffee, that when you first arrive in Berlin, you go for to meet someone for a coffee, and it takes a half an hour. Then it takes an hour, to two hours, to four hours. And in your personal life, you move from having a romantic love affair to a tragic Fassbinder version of a love affair. I found myself at the end of my time in Berlin having a 4-hour coffee with a friend, weeping over a broken heart, and in this moment I realized it was time to leave and come back to New York.

MK: Did you feel like a New Yorker, or an American, while you were there?

SdB: I felt like such a New Yorker.

MK: To not feel settled or satisfied!

SdB: With anything.

MK: I wanted to talk about some of the different installations you have made in different environments. The High Line piece, “Haunt Room,” for instance, seemed incredible in that space. What was it like working outdoors like that, to create a structure in an outdoors environment?

SdB: I enjoyed it. It was a different kind of audience; it was a broader audience. I was surprised that was the piece that they wanted. It was the most aggressive piece that I proposed to them. The work was an audio tone in a public place that made you feel sick. The curators and the trustees of the board of the High Line believed in that particular piece, and wanted that particular piece. It was creatively challenging, as well; I had never made an outdoor installation before. It’s hard to control audio levels in an outdoor space.

MK: And working with the general public, it’s interesting to prepare something for a gallery exhibition than something that will be on the High Line, even though it’s only a block away. Is that something you were thinking about when you were making the work?

SdB: Maybe. I’m interested in that site. It’s created this new landscape; it’s a new way of looking at the city, at the topography of New York City. I worked on the piece while they were building up the new section and I liked walking through the new section while it was under construction. I am also interested in non-art. Perhaps I find it interesting because I came to contemporary art so late. I feel like the gallery’s audience on the one hand is very rarefied; it’s a small group of people, but one that is open to absorbing different kinds of perspectives.

The only thing I wasn’t thrilled about was they had to put up a warning sign that the audio may make you sick, and I felt like the warning sign created a new dialogue about what the piece was supposed to do. That maybe did a disservice to it. The warning sign said something like, “This artwork might cause depression,” and I think that really for that to happen you would have had to be next to the speaker for significant periods of time. But I think legally, in America, in a public space, you need to present the worst-case scenario.

MK: Your work then often seems inspired by site. You have the space first and then the work is designed for the space- is that usually the situation?

SdB: I love that. It’s like that with shooting, as well, working with people. Making art is a dialogue, the back and forth.

MK: I suppose in the end it is solitary, because it’s you editing, and it’s not a typical studio environment. But you’re still working with people so that you do get continuous feedback and advice.

SdB: I think it’s the working process where I have many people around me or I am literally just working on my bed. I need time alone and then I really need to have people around to get the conversation going.

MK: What are your thoughts in general about the New York art scene? Would you describe it as somewhat collaborate or more disparate? Is there a general feeling about the way that art circles and things move within each other, something pretty natural or maybe not as much as it was say three or four years ago?

SdB: I think it has more to do with age. I know as a young artist my peers were extremely collaborative and in constant dialogue. At a certain point these people’s careers lifted off and it became more paranoid and territorial. I like working at universities because there is a permanently young element engaging in dialogue.

MK: There are so many schools and so many students here, which does create great artistic communities. This is somewhat unusual. For instance, when I’m in Miami there are only a couple schools down there. From the conversations I have had with people I have found that they find that very frustrating so they often bring in people to do talks, panels, in order to create these conversations. Because that is something that they feel is very necessary and needed. From your community, do you get a lot of information or feedback from the students or from the other faculty?

SdB: Yes. I think to be affected by your students you have to be open to it and I think that can be exciting. It also involves humility. On the other hand, you have brilliant people come through and then to be able to watch them develop is it’s own kind of privilege.

You know, I have a group of friends that are artists and I rely on them; they’re pretty key people for me. But in a certain way, in time, you start talking more obliquely about artwork you are working on, and more often the conversations are about whether you have seen a show. Mid-process in the studio is a private time, and you discuss a body of work when you have finished with it. When you’re in your twenties you want to talk about whether you should have used something different in a particular piece; how does the duct tape work for you? It’s specific, muscular, different.

MK: Did you have a film background from school?

SdB: No, my interest in film came about gradually. I majored in painting as an undergrad at Parsons, but I primarily took photographs, staged photographs. And then I went to Columbia for grad school. There I worked with Jon Kessler and Troy Brauntuch. Troy had made this incredible body of work, but when I met him it was a quiet moment in his career.

I shot my first video at Columbia. Initially I just shot myself; I would set up lights, and try things out in front of the camera. But I didn’t really want to shoot myself; I found it to be limiting, too diarist and strange. I think that working in a collaborative team, getting comfortable working with other people, was an important step for me.

MK: There is a huge influence of modern Goth in your work and I read that you have an interest in horror films like “Halloween”?

SdB: I love “Halloween.” I wish Halloween was every holiday.

MK: Also teenagers, teen fiction novels are an inspiration.

SdB: For a while, it was very important source material. I think that I was interested in adolescence partly through the idea that it is a short window of time, yet is so important.

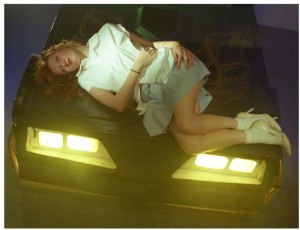

When I first started shooting other people, they were young people. I was interested in the fragility of that time period, and how exposed they looked on film—raw. Youth is also a radical time, because you don’t have to live with the consequences of your actions; your actions are done in broader strokes. I did a number of works using young people until I became frustrated with the dialogue around my work. I also felt like shooting only young people was becoming a crutch to get that kind of raw-ness in my footage.

MK: There is a kind of parallel with this type of recklessness to horror or gore.

SdB: Yes, you change your life or break it apart in that one moment of violence. I was raised in New England, and New England has a violent history that has marked its sense of aesthetics. Witch trials. There was a heavy religious component that was mixed with the occult, violence between early settlers and American Indians (gory deaths, kidnappings). This was the foundation and it has colored the culture that grew out of it.

MK: So something like The Crucible is an interesting kind of relationship, tying all of that together with teenage vulnerability and femininity. It is interesting that you’re now making a piece in a basement!

SdB: I know. I was so excited. No windows down here, perfect. They had offered something upstairs and I said no, I really want the basement. It’s my dream space.

Tags: Journal