Interview with Sarah Charlesworth by Meaghan Kent 12.8.98

In the series of interviews presented in this Journal, I asked each of the artists what their motivating factors were that brought them to New York and if those reasons still resonate now. A significant moment for me was an interview I conducted with Sarah Charlesworth after her solo exhibition at SITE Santa Fe in 1998. I was completing my undergraduate thesis on postmodern feminism. I interviewed her over the phone; Charlesworth in her studio in New York while I was in Santa Fe. I could hear the sound of New York traffic in the background and I couldn’t help but find it foreign and extraordinarily exciting.

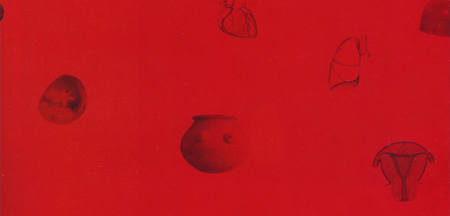

As I prepared for “New York Practice” over the last several months, Sarah Charlesworth and our interview has been on my mind. Included here is an excerpt from that interview.

Sarah Charlesworth: I was doing my first shows in New York in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s at the same time as Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, Laurie Simmons, and Barbara Kruger. We all emerged as young artists at the same time. I think we have all been influenced by similar things.

Using photography as a medium and appropriated imagery has a lot do with issues in the generation just slightly older than us. I was particularly influenced by Conceptual artists in New York but also LA, such as John Baldessari and Ed Ruscha. Also, Pop art was a big movement when we were in college. But the larger cultural issues as self-expression was a big looming subject that hadn’t really been addressed.

Meaghan Kent: Postmodernism was coined in New York in the ‘60s and spread throughout the ‘70s. When did you first hear the term?

SC: There was book in the late ‘60s—early ‘70s that I remember as the first time I learned of it; it was about architecture, postmodern architecture. It had very much to do with the use of quotation and the idea of mixed metaphors; it was drawing from other sources rather than using a traditional style, more of an eclectic style. Eclecticism in itself is not interesting; it was the underlining fact that we live in a culture which draws from a different number of sources. There isn’t one specific American source or culture. There isn’t one that defines who we are. It is a blend of influences and histories that are, in fact, present in contemporary experience.

I think with architecture these are part of the traditions that we inherit, so different idioms were borrowed rather than one pure style. The idea of mixed quotational references was very much part of what postmodernism meant. I remember initially rejecting the idea because it initially meant everything and anything that came along.

The first time I heard it used to refer to my work was in a panel in 1983. Douglas Crimp was the moderator of the panel and he taught postmodernism and photography. I hated the word and I tried to reject the word. On the other hand, it seemed like modernism had run its course. There was something else that was emerging and that something else grew from a new kind of cultural experience that was very different from the modernist experience.

MK: In your work, what were some of the distinguishing factors?

SC: I think it has a lot to do with technologies. The way culture has experienced everything from jet travel to TV. Because there is so much sharing of imagery and languages. The moment where we can buy food from every culture. New York, for example, with its different cuisines. These cultures influence each other in so many different ways.

In terms of postmodernism, it seemed to jump off from the point where modernism didn’t have any more questions to ask but there were lots of broader issues that art could address. There was the Feminist Movement. Throughout history, right up to the ‘50s and early ‘60s, women were definitely considered second class citizens in every possible way, in spoken, written and visual language. It took a generation of artists, writers, anthropologists to articulate that this way of viewing ourselves doesn’t empower women. We refer to artists, presidents, and lawyers as he and man. We’ve always created imagery that advanced male culture but doesn’t advance female culture. These feminist and racial issues simultaneously took place with the emergence of postmodern culture and had very much to do with getting outside the “art for arts sake” model.

MK: And that’s why you created, or attempted to create a new language?

SC: Very much so, yes. The women of my generation didn’t want to be considered a woman artist but an artist and they wanted to be able to participate in the same galleries, museum and magazines.

It took a group of women twenty-five years ago to push the idea that an artist or a doctor or a lawyer could be a she too. So we’ll make that space in that language for that possibility by saying he or she. It makes a huge difference. It makes possibilities for people to be able to invent themselves.

Sarah Charlesworth 1947—2013

Tags: Journal