02 04

02 04

DOWNLOAD PDF: site95_Journal_02_04.e

Editor in Chief Meaghan Kent, Contributing Editor Janet Kim, Copy Editor Beth Maycumber, Copy Editor Jennifer Soosaar, Copy Editor Kati Henderson

Curated by Daniel McGrath

Contributors: Pablo Helguera, Emily Stremming, Amanda Leigh, Ross McDonnell, David Johnson, Kim Seymour, Megan Koboldt

Journal designed by SITE, Logo designed by Fulano

The Florentine Nights Network by Pablo Helguera

“And you always loved only chiseled or painted women?” tittered Maria.

“No! I have loved dead women too,” replied Maximilian, as a very grave expression came over his features. —Heinrich Heine, The Florentine Nights

The spirits speak, despite the hypnotizer and the hypnotized. —Julio Torri

Those of us who worked for Isidoro Blackstein always wondered what would happen with his life’s work after his demise. We were all fairly certain that he had no close relatives. His house, which also functioned as a studio, was a strictly impersonal place, with no sentimental objects of any kind: no photographs or items with family history. The only person he had any apparent relationship with was his sister, who had passed away a few summers ago in Italy. His incessant work and worldwide travel allowed no time to be intimate with anyone. He was to all of us, by far, the most frenetic traveler we had ever seen—rarely staying put in one city for more than three days. He had traveled to more countries than a National Geographic journalist; he knew every airport in the world. His bathroom was full with hotel soaps and airline toothpaste tubes.

It was only the three of us, who at different times alternated being his assistant—none of us could last very long due to his difficult personality, but all of us would always come back for a time, in one way or another, as we could not bring ourselves to abandon him completely. In the end, despite Blackstein’s temper and self-absorption, there was something endearing, there was something about the work that he was doing that transcended him and us, even if we quite didn’t understand it—we knew it was important to preserve.

Blanca was the only one who dared to ask him the question once, something along the lines of, “Have you given any thought to what you want to happen with your research after you are gone?” to which he replied, “it’s for you guys,” in the most natural way, as if all along it had been clear that Blanca, Trevor and I were his adopted family.

And so it happened. One fatal day, I received a call from his cell phone. Blackstein had passed away on a plane going to Tokyo.

Before we knew it, we had to deal with his enormous archive. The three of us knew that it would be our mission to finally make sense of it, after so many years of working on only bits and pieces of research. His Lower East Side studio and apartment was only a portion of the problem. More daunting was a home he had in the country, to which none of us had ever been invited. We knew it only as the place where we were always asked to send large shipments of documents.

He wanted everybody to keep in step with him. I thought how difficult it was to do so, especially as we went through the dense woods. It had rained the night before and there was mud everywhere. We walked though quicksand areas. I was having a hard time with the incessant attacks of mosquitoes and the humid heat of mid-August that made the air almost unbreathable in that part of the Adirondacks. I was so impressed with Blackstein’s former agility and physical condition that once allowed him to traverse this area to get to his house.

The house was truly hidden. The property had belonged to the university for over a hundred years, a donation by an alumnus. At some point in the 1920s, the geography department made plans to create a summer institute. Construction started in the 1930s but soon stalled, and the university abandoned the project. In the summer of 1961, the year Blackstein started teaching, he and Professor Erick Thomanson assessed the condition of the building for the department. At the time this truly was an abandoned part of the world. It still is, I suppose, although highways have been built, and small towns have since emerged. As no one in the university saw any value in this building, not even the value in selling it, Blackstein claimed it once again as a location for his department’s summer institute—a project that would never in fact come to fruition. At first there was a good deal of objection to his proposal, but over the years everyone simply forgot this building was there. “It’s sort of a nostalgia thing,” Blackstein would say, whenever he was asked why was he heading there. It had always been my impression that Blackstein was seldom there. Whenever he was absent, I imagined him in Kamchatka or the Himalayas, not in this large and inhospitable building. But as we entered the space, we knew it contained a key to his life.

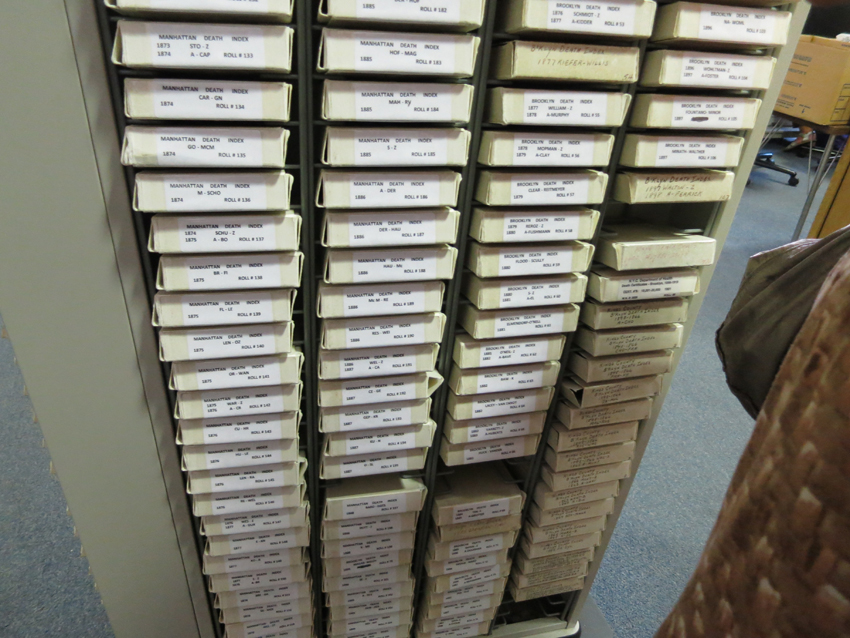

When we first entered, we all became very quiet. Nothing could have prepared us to see the monumental display of photographs that was there. After two years of cataloguing, even as of last week, we knew that we had yet to reach even a quarter of all the material. Yet, arriving there, we had suddenly accounted for three million prints. The space was organized like a postal office, with piles of prints arranged by what appeared to be zip codes. Blackstein had taken copious notes: several hundred thousand pieces of scribbled paper lay inside cabinets and binders, some of them so yellowed they were clearly from many decades before.

It would be unfair to say that this project was a hopeless mess, but we also knew that the moment we informed the university that this material was here, there would be a quick movement to retire it, and possibly even to discard it. We knew of the general lack of interest in engaging with Blackstein’s ideas held amongst his university colleagues, who always saw him as an arrogant and self-absorbed character. They were right, but we also believed that Blackstein’s demeanor had less to do with certain misogyny, but rather with a definite and complete indifference to humans.

He had written about this subject many times. Once when asked why he had become a geologist, he had said that he wanted to detach from humanity as much as possible, not because of hatred toward humans, but because “human presence always makes understanding impossible.” He clearly suffered by being human himself, and was always making an effort to erase or at least substantially minimize the fact that the observer of a phenomenon alters it by the mere act of their observation. I will now make what will likely be a poor attempt at representing Blackstein’s ideas and how they manifested in his life’s work.

Blackstein spent the last fifty years of his research focusing on the subject of conversations without living beings. To Blackstein, conversation had a different meaning than it has for someone like you or me. To him, consciousness was not merely a human attribute and, perhaps also surprisingly, he did not see it as a spiritual one either. He spent most of his life trying to prove first that spaces have genealogies and interests, elective affinities and weaknesses, and that these attributes made them attractive to other, parallel places. He went out of the way to alert the reader (who he thought of as the reader was always perplexing to me—was he writing for us, his assistants?) that he did not believe in extra-sensorial forces. Rather, he believed that geographical locations had “qualias.” It is perhaps meaningful to add here that Blackstein had studied under Clarence Irving Lewis, who in his book Mind and the World Order had first articulated the notion that:

“There are recognizable qualitative characters of the given, which may be repeated in different experiences, and are thus a sort of universals; I call these “qualia.” But although such qualia are universals, in the sense of being recognized from one to another experience, they must be distinguished from the properties of objects. Confusion of these two is characteristic of many historical conceptions, as well as of current essence-theories. The quale is directly intuited, given, and is not the subject of any possible error because it is purely subjective.”

Blackstein was heavily influenced by Lewis’s idea, though he rebelled against the notion that qualia would be necessarily an attribute that could easily be detached from objects and limited to humans. According to Blackstein, “just because we as humans possess consciousness that allows us to make sense of the world and become aware of our own awareness, this doesn’t allow us to conclude that things, or places don’t have a version of awareness of their own.” “This is not to say,” Blackstein added in his notes, “that places have feelings or a thought process, but they inhabit their identity in the same way in which we inhabit a state of mind, for which we don’t need to have a reflection about when we are inhabiting it.”

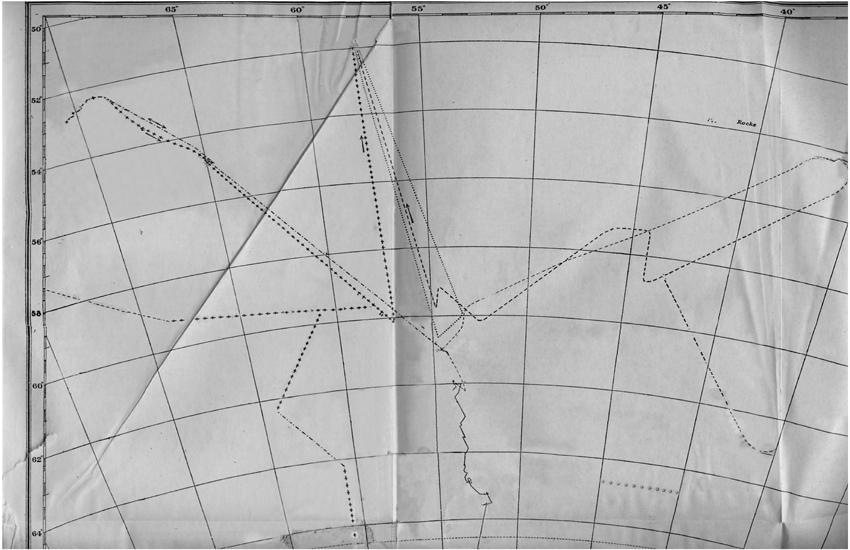

This line of argument eventually led Blackstein to what would become his half-century quest to identify forms of qualias for various places, forming taxonomies and traveling to distant lands to recognize familiar relations between one place and another. He believed that in the formation of the planet, most of these locations had been together at one point, and as the earth’s pangea had separated, these places had also detached from each other, eventually spreading throughout the world. Blackstein had created a taxonomy for those places:

Network 1- places of abandonment

Network 2- places before violence

Network 3- sites of vicarious living

Network 4- storage spaces

Network 5- places that pretend to be other, distant places

Network 6- places that contain objects from another time

Network 7- haunted places

Network 8- historically recreated places

Network 9- the space between sky and earth

Network 10- places in waiting

Looking at Blackstein’s notes, it is very clear that this particular breakthrough in his research came at a very early point; he must have been in his early twenties when he made these initial observations. What came over the ensuing five decades is clearly a development of the natural consequences of these ideas. What we always thought was a geological study of subsoil at the locations he was traveling to and the documentation he gathered of those places, was in fact a continuous and methodical series of journeys to create a map of geographic qualias, trying to find the ultimate typologies for different man-made and non-man-made locations (to him, the intervention of the human hand was irrelevant; he believed that any intervention was always meant to result inevitably in the furthering of the already existing identity of that place).

As it happens to most of us, Blackstein’s efforts were cut short by his own demise. His final conclusion, which he clearly thought he was close to writing and disseminating, never saw the light of day. For those of us who knew him, we could always recognize that while he held himself to the most critical standards, he never felt lost. Instead, he was someone who had a puzzle in front of him and knew what needed to happen—he only labored to find the right places for the pieces. Thinking in retrospect, only once do I recall sensing that Blackstein betrayed doubts of his work. It was an exchange that stayed in my mind and which at the time did not make much sense. As we were working on organizing the documentation of one of many thousand sites, he seemed to be deep in thought. He asked me:

“If you were a place instead of a person, what kind of place would you be?”

“Do I get to choose?” I asked, thinking it was a game.

“No. I am asking what sort of place is the equivalent of what you are right now, how you feel right now.”

I remember I couldn’t quite give him an answer. But I never forgot his question. And today, after thinking about him—his constant mobility and his inability to stay in one single place for more than a day or so, I finally understand that to Blackstein the real challenge had never been to create a unified theory of qualias and places, or a geographic theory of consciousness. It was to find the place equivalent to him. His summer home, with the millions of photographs, was perhaps his way to search for a location, or rather, to convince himself that he could find himself comfortable in one place and merge an identity with it, regardless how inhospitable it became. It was some perverse way, perhaps, to prove that he and his theories were right. Perhaps he realized that he was in search of an ultimate location that is permanently changing, like Heraclitus’s river, always gone or distant by the time he arrived to grasp it, leaving him to forever pursue his own shadow.

Weaving Through The Street by Emily Stremming

What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially. —Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography

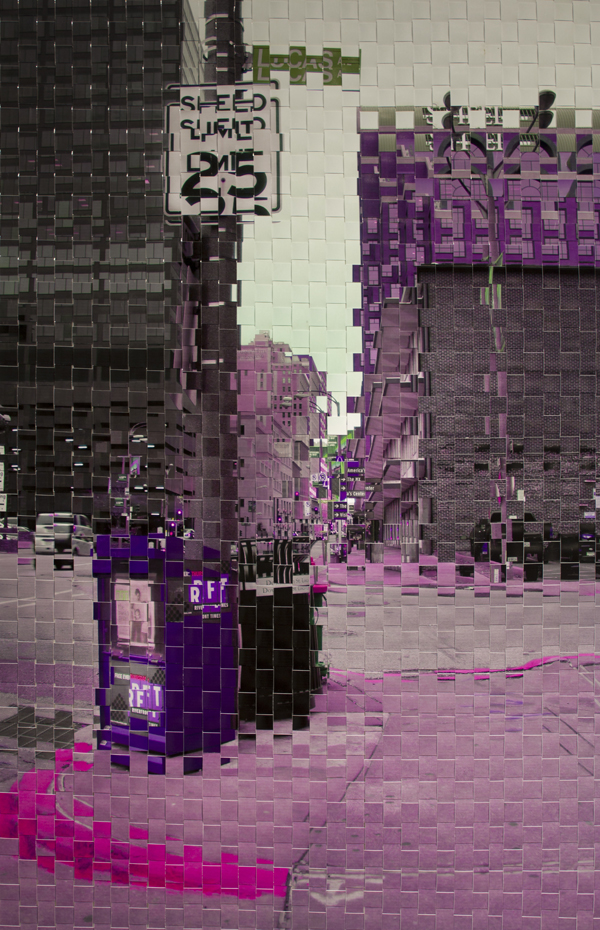

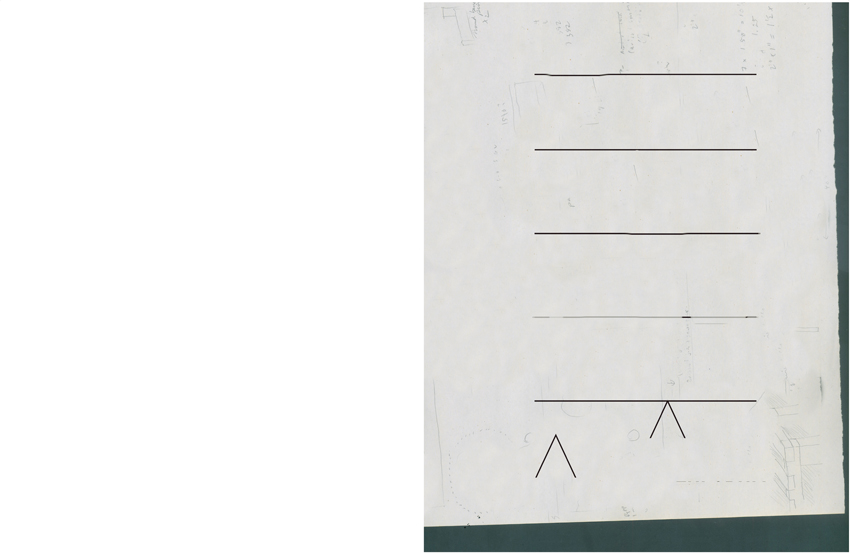

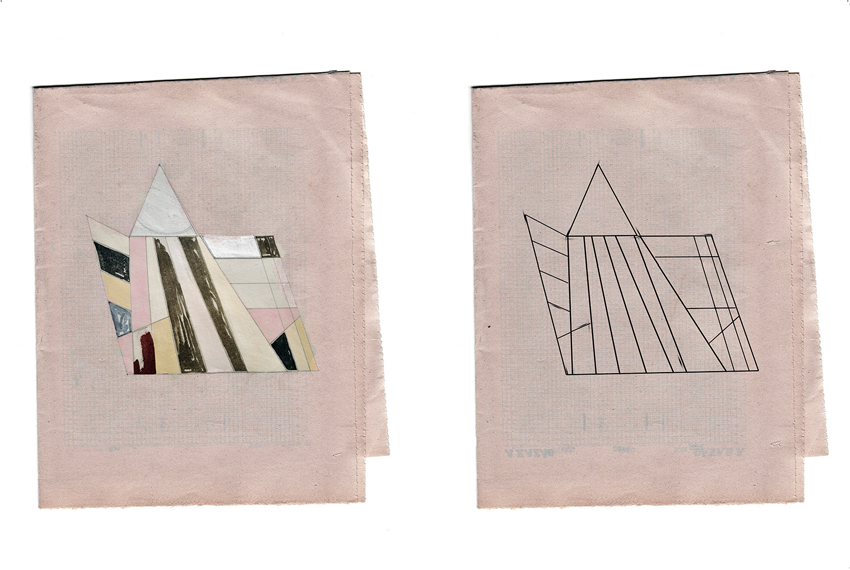

Emily Stremming weaves together photographs of specific mapped locations in St. Louis, Missouri, which stemmed from a previous series, Typologies of Alleyways: St. Louis, Missouri. There is a hint of Eugene Atget’s deadpan documentation of Paris fused with Dihn Q Le’s mnemonic play with sense perception in this series. While photographing deep fields of space in the initial work, she began to examine the flatness of the photographic paper that conflicted with the negative recesses of the alleyways that extended to horizon lines and vanishing points. In the completed series she physically manipulates the photographic paper by cutting into the larger prints and reforming the image to disturb a stable sense of place in the photograph.

This is an alchemical process that atavistically recalls Fox Talbot’s early experimentation with flimsy paper negatives and the more contemporary example of Vik Muniz’s crowd-pleasing paint/photo grid hybrids. The ‘image’ itself is broken when ripped out of an original context, but by reweaving the prints, a sensation of a fragmented point of view is created that subverts the ‘a priori’ fixed vantage point that defines photography’s history, the related concepts of linear perspective and its visual history in western art. The act of weaving becomes a small but significant rebellion against mechanical reproduction. The perceived image itself becomes a flattened, distorted representation depicting a space that we could not experience in the real world whilst the actual surface melts into a subtle low relief, almost a frieze, as it gains the flexible texture of a woven textile design. The interaction of the viewer with the picture varies considerably, sometimes this depends on how well versed the individual is, in photographic conventions established by masters like Atget and by the attendant, handmade disruption that is introduced.

While some images are more prosaic or familiar than others, they all invite closer examination to determine where the photograph was actually taken or if any ‘POV’ can be determined at all. Literal or visual hints about location are present but they slip and slide unsteadily generating a roving focus as the eye darts around to find a comforting focal point. These are images that also violate notions of photographs as infinitely reproducible objects: they all have a distinct existence as ‘one offs’ laboriously or if you prefer lovingly, worked on to completion. The evolution of the digital age of photography, where even location of the snap shot is recorded down to the last centimeter via satellite location, leads one to question the technological, and conceptual and perhaps even the ethical limitations of the camera and its place in the world.

Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City by Daniel McGrath

Mankind which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympic gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction with as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.

Artists depicting war and its terrifying consequences are not afraid to hold a mirror to the darker side of human nature, exposing the fears and irrationalities that drive us on to obliterate and damage the lives of other human beings. Shomei Tomatsu’s image of a Hiroshima victim’s hideous scars is a reminder of the twentieth century appetite for killing on a grand scale. Every living person looking at this image must realize that: ‘he too is a “human negative” waiting to be processed.’(II) Tomatsu’s photograph is an intimate portrait of suffering. Other paintings and sculptures like Picasso’s “Guernica” (1936) that depict war are considered masterpieces of civilization. Arguably, modern societies are better educated about the consequences of wars today, as a result of omnipresent electronic imagery than the generation that produced Picasso.

As Walter Benjamin spells out though, rather than sensitize us to suffering, the flood of imagery may be one of the factors contributing to the opposite effect—leaving people alienated and violent.(III) The ‘War on Terror’ itself increasingly seems to be dictated by the characteristics of electronic and photographic imagery. Indeed, with recent events in Boston in mind, it is the photographs we associate with current events which are becoming defined by neologisms and new-fangled technological “meta” issues. By pushing the button that exploded the bombs the Tsarnaevs started a media machine.

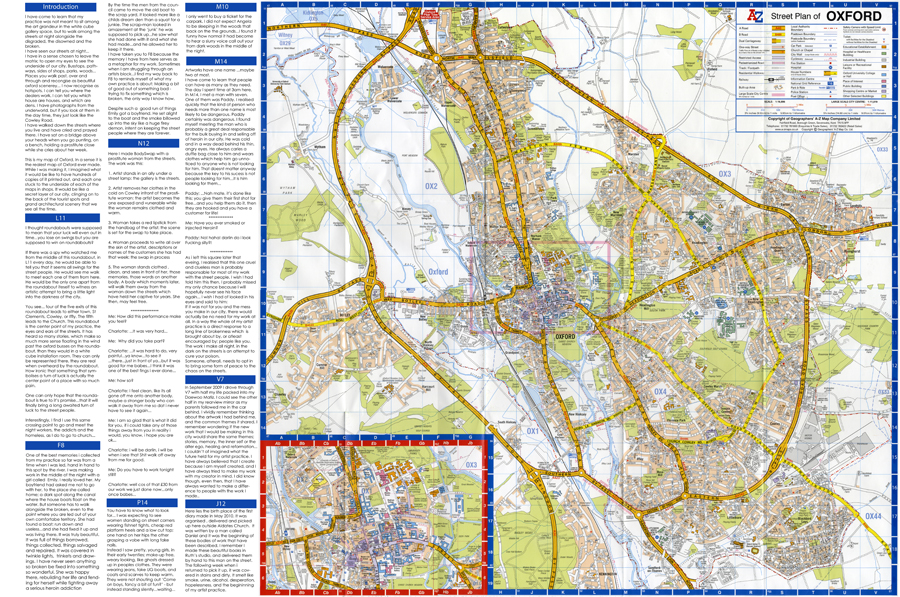

“Crowd Sourcing” is the newest trending technique whose reputation has risen and fallen with the 24-hour news cycle. It is an online, distributed problem solving and production model, often used to attempt to solve crime via the analysis of publicly available forensic evidence, such as the meta-data contained in imagery and embedded computer code. The coordinates N 42° 20’ 56.871”, W 71° 4’ 51.3804” logged onto the meta-data of Tweets and photographs became critically important for the pioneers of this brave new research model. Even responses to the bombing via Twitter were mapped with geo-tagged references to “#boston,” whose frequency correlated with distance from the bombing. Amateur detectives began to pour over data to identify potential bombers. Most of the identifications proved to be spectacular errors that caught runners and various onlookers in the dragnet. The reality was more prosaic—a pair of inconspicuous brothers casually walking along the pavement gradually emerged as suspects.The map of #boston is dry stuff, but according to the blogger of Floating Sheep: “This analysis shows how established spatial patterns of place-based social media activity can be disrupted by extraordinary circumstances, such as a terrorist attack, as well as the importance of looking at how such spatial patterns change over time.” To what purpose this is useful, be it commercial or social, remains to be seen.

Twtter and Hashtag arrays in the wake of the Boston marathon bombing. Source www.floatingsheep.org/2013/04mapping -boston-bombinh.html

However, every act of terror is registered, analyzed, and narrated by the media which is rapidly automated. In addition to the geekier reaction there was a great deal of juicer tattle from social media. Once the suspects were identified, short fictions about the suspects worthy of Jackie Collins were immediately written. Even the turgid romance writer, Barbara Cartland, called Collins’ work “nasty, filthy and disgusting.” Her best selling book, appropriately enough for this comparison The Love Killers,1989, depicts a very public assassination in Central Park. She magazine called it “Sensational, bitter, completely compulsive…” The ravenously obsessed Tsarnaev fan club takes Collins’s pornographic aesthetic to the edge and crosses right over it. The following is not an excerpt from a Collins novel but Tumblr account Free Jahar! which is devoted to the alleged angel faced assassin:

[Dzhokhar] sounded much more terrified than you could have possibly been. “Are you okay?” You begged him to tell you he was fine, nobody really knew. “I’m hit, in the leg, but I- wait what? You’re asking if I’m okay?” He was surprised, but calmer now. “I know you didn’t do it, and even if you did, I know you aren’t harmful.” He sighed with your words, he felt safe for the first time since he saw his face on the television.

At first most reporters hoped the Boston Bombers were Tea Party Rednecks, or, according to Reddit “Crowd Sourcing” sleuths, a variety of assorted middle-aged paunch-bellied losers or a Saudi overstaying his student visa. Sadly no, behold the face of terror ye mighty and despair! It was Zooey Deschannel’s little brother and his cute floppy hair. What could be more appropriate on the “internets” than a dose of conspiracy theory and breathless porn rolled into one nylon-black-backpack story?

The geo-location devices that enabled investigators to amass the meta-data lurking behind every cell phone snapshot at the finish line of the Boston Marathon didn’t see this one coming: pastebin.com/raw.php?i=1gRSS5ZB wherein 50 Shades of Grey meets Jihad. The outlines of social media and technology are exposed and turned inside out all at once as Dzhokhar, on the run and on the job, turns out to have been hiding away on a porno film set, in the mind of one frenzied fan-girl:

“He kissed your neck, sucking on it to leave his mark, biting down every now and then. When he breathed out you got chills down your spine, making your nipples hard when he squeezed them. ‘Cmon baby, give me something to think about in jail.’”

It’s racy stuff. If you are an aspiring international terrorist it certainly pays to be a cherubic fallen angel, a fresh-faced man-about-town.

Gawker quite neatly cataloged the atrocities on Dzhokhar’s twitter feed: gawker.com/5995065/is-this-the-boston-marathon-bombing-suspects-twitter-account. Dzhokhar chillingly Tweeted Jay-Z/Bobby Bland lyrics after the bombing and before his capture: “Ain’t no love in the heart of the city, stay safe people” demonstrating a blend of bravado, lyrical obsession and callousness that would make Mark David Chapman (assassin of John Lennon) proud. This is the first large bombing in the US in the age of social media, so the unfolding drama will likely take many more twists and turns in the social-media funhouse. But there is something eerily familiar about the Boston attack. Young men assimilated into western counter-culture like hip-hop, consumer goods like Nike and Mercedes, and foster an interest for the black-flag of Jihad. Here are the coordinates for the first installment of the tragedy part of this repeating history: N 51° 31’ 49.5618”, E 0° 7’ 26.0286.”

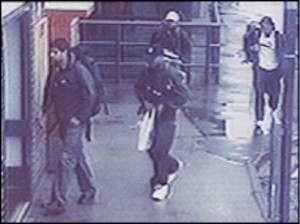

This happened before Twitter. The suicide bombers who attacked London 7 July 2005, looked like ordinary backpackers going on holiday. They were, of course, carrying explosives in their rucksacks. The image of these men casually strolling through the entrance of Kings Cross, one with a plastic shopping bag another with a baseball cap, through the dreary puddles is only made remarkable by the knowledge of the destruction they later wrought. However, the scene’s ordinariness carries its own menace. The fact that the picture appears to be from a security camera implies that a crime is in progress—the picture in its own prosaic dullness carries a sense of threat.

The exchange of violence between al-Qaeda, Iraqi insurgents and the American coalition in the ‘War On Terror’ is often conducted through acts of violence that place a premium on creating or destroying visual iconography. These images are the currency of bloody symbolic exchange. Most of the targets selected by al-Qaeda and its successor groups have little conventional military value, but rich symbolic value: statues, skyscrapers, the London Underground, Bali discotheques, and double-decker buses. Otherwise, they mimic horror films with hostage ‘snuff’ videos.(IV) All bombings directed at familiar tourist destinations and famous landmarks amplify the horror of the carnage. Some targets like the USS Cole or the Pentagon have obvious military value, but against such targets al-Qaeda campaigns of attack have been small, improvised, weak and unsustainable affairs in comparison to the enormous offensives launched by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in WW2. Their operations resemble ‘ghazi’ raids rather than total war, because the attacks are not primarily designed to capture territory, kill key military personnel or even assassinate high profile politicians.(V)

‘CCTV photograph of July 7 bombers entering King’s Cross London underground station,’ Associated Press

According to one British officer in India, the ghazis on the Northwest Frontier were only a small fanatical percentage of an opposing force that normally tended to mix bravery with a highly developed sense of running off before getting killed: ‘But when excited by their ghazi brethren, elated by success, they are resolute and bold…their daring and courage is of the most reckless description.’(VI) The ghazi fought to inspire their more circumspect allies, to instill determination and increase fighting spirit. This is similar to the ‘inspirational’ role that al-Qaeda have self-consciously adopted for their global campaign of terrorism.The bombings they carry out certainly serve as a symbolic rallying point for their less ferocious confederates. The bomb designs themselves are downloaded electronic blue prints. Osama bin Laden is still considered to be a hero in parts of the wider Islamic world and symbol of Islamic resistance to America. Opinion polls indicate he was more popular in Pakistan than President Musharaf (now languishing in jail) and more highly regarded than the ibn Saud royal family in Saudi Arabia.(VII) Because al-Qaeda bombings are symbolic gestures, designed to foster more ‘daring’ in the wider Muslim world, the bombings themselves do not add up to the type of national security threat the military or police are typically designed to combat. The hysteria and city-wide shutdowns surrounding the capture of the bombers in London and in Boston belie the relatively small impact the actual bombs cause. However, bin Laden’s ghazi-like organization has proven to be more resilient than previous opponents of the US Army, like the Axis—surviving everything the coalition has sent for over a decade, and even hitting back in western metropolitan areas long after their own base camps in Afghanistan were overrun and the leaders killed. Like the ghazi, a new breed is prepared to ‘lie concealed for hours in the hope of cutting up and mutilating some unarmed straggler or follower, or better still, shooting some armed man and possessing himself of a rifle which is worth its weight in Silver.’(VIII) Almost all attacks take the form of ambush and massacre. So far their cadre of ghazis remain a force to be reckoned with despite the efforts of conventional strategies.

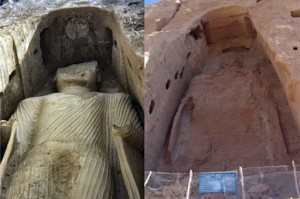

YOUTUBE BEFORE YOUTUBE – BAMIYAN

A key symbolic precursor to the ‘War on Terror’ occurred in February 2001, events whose portentous significance was ignored until the World Trade Center attack on 11th September 2001. Two Buddhist monuments in Afghanistan were gleefully blown up and their destruction broadcast by the Taliban Government of the Emirates of Afghanistan. Appropriately, the attack was carried out on monumental sculpture, for the Taliban were preoccupied with sacred iconography. The Taliban’s official policy toward images remains unremittingly hostile: cameras, advertising and satellite television were ‘banned’ under their laws. Contemporary Muslim societies are saturated with advertising billboards depicting fresh-faced actors endorsing the latest consumer gadgets, figurative paintings of leaders or heroes, and political cartoons in even the most conservative Arabic newspapers. Ancient monuments and archeological dig sites are considered to be the crown jewels of national heritage—the Pyramids and ruins of Babylonian and Roman civilizations are assiduously cared for by governments as diverse as Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Turkey. In spite of this example and the exhortations of other Muslim leaders, the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Omar, decreed the destruction of all statues in Afghanistan, including the ancient sandstone Buddhist statues at Bamiyan. The Taliban stated that:

In the view of the edict of prominent Afghan scholars and the verdict of the Afghan Supreme Court it has been decided to break down all statues/idols present in different parts of the country. This is because these idols have been the gods of the infidels, who worshipped them, and these are respected even now and perhaps may be turned into gods again. The real God is only Allah and all others false gods should be removed all other photographs and electronic images should be likewise forbidden.(IX)

This statement was a declaration of war on iconography—particularly on Buddhist sculpture—but the Taliban themselves filmed the destruction of the Buddha and made the footage available to world media, ignoring their own iconoclastic dictates in order to generate footage that suited their purpose. The destruction can be seen as a warning shot aimed at all prominent buildings or monuments, an eerie foretaste of the collapse of the World Trade Centre in 2001.(X) It’s tempting to categorize it as the prototype viral video.

For many art historians, Bamiyan’s destruction felt like a declaration of war on their profession. Western journalists, however, smirked more often than they condemned. One latter day Savonarola quipped: ‘We could have turned the Guggenheim and Whitney museums upside down and shaken them lightly, and—to the net gain of civilization—offered up dozens of works to the Taliban’s immolation.’(XI) Art world professionals are generally more sensitive to this sort of cultural vandalism than the average western politician or journalist. A curator’s role is analogous to a pit canary in that they are often the first people to smell the poison seeping from the seams of violence.(XII) The public release of the Bamiyan videotape produced a flurry of apprehensive communications between museum directors and within curatorial departments.(XIII) One archeologist even managed to hit upon the “absolute moral superiority” rhetoric of which President Bush and Prime Minister Blair mastered in condemning international terrorism as a new evil a few months later. The statement: ‘any destruction of archaeological remains is an indefensible crime against humanity. I fear archaeological terrorism—this ultimatum of “give us what we want or we will destroy our enemies’ (and the world’s) heritage,”’(XIV) Predictably, however, calls from art professionals to check the wave of symbolic violence went unheeded; the monuments’ destruction was a precursor to when Manhattan’s towering monuments to capitalism were smashed. The looting of Iraq’s museums and archeological dig sites were likewise a precursor of the chaos of an intractable guerrilla campaign and not an example of the progress or ‘messy freedom’ claimed by some politicians.(XV) W.L. Rathje, in another context, of course, could be credited for formulating the Bush doctrine of the War on Terror.

Terrorism literally transformed images into weapons and cameras are themselves detonated like bombs. On Sunday the 9th of September 2001, the veteran commander of the last remnant of anti-Taliban forces in Afghanistan, Ahmed Shah Masood, was giving an interview in the northern province of Takhar to two Arabs posing as journalists. The “journalists” detonated a bomb concealed in their video camera. Masood was killed in the attack. Within two days, passenger jets piloted by terrorists posing as passengers were used as bombs in the most videoed massacre in history. And so it goes… in Boston as, Twitter, Tumblr, Youtube and ubiquitous smart phones act as force multipliers in an escalating tit-for-tat slugging match defined as much by the scars images inflict on the mind as the havoc bombs cause on flesh and blood.

I Benjamin (1936), p. 520

II Ewing (1994), p.238

III Ewing (1994), p.239

IV Nick Berg in Iraq and WSJ reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan were horrifically butchered by al-Qaeda terrorist captors: both murders were videoed and the tapes distributed to Arab news channels like Al-Jazeera or the internet. The beheading video acts as a catalyst for terrorist recruitment, and is a quick and dirty way to scare off foreigners.

V Amer Taheri ‘gazavat’, The Times, 8 July 2005. His suggestion is the most apt comparison to al-Qaeda’s tactics. The historical ghazi carried out hit and run raids on the Islamic frontier, rustling cattle, massacring sleepy farmsteads and villages followed by a quick retreat to the safety of a remote base camp. The modern incarnation of the ghazi in Taheri’s formulation is working toward the re-establishment of the Islamic Caliphate and to subdue the ‘infidel West’.

VI Shadwell (1898) p.318-19.

VII Available from: cnn.com/2004/WORLD/meast/06/08/poll.binladen/. The poll interviewed 15,000 Saudis: conducted by Nawaf Obaid, a national security consultant. Conducted between August and November 2003, after simultaneous suicide attacks in May 2003 when 36 people were killed in Riyadh bin Laden’s popularity took a small tumble. Almost half of all Saudis said in a poll conducted last year that they have a favorable view of Osama bin Laden’s sermons and rhetoric, but fewer than 5 percent thought it was a good idea for bin Laden to rule the Arabian Peninsula.

VIII Shadwell (1898), p. 318.

IX Ibid. p. 411.

X Viewing video footage from the two events a striking similarity becomes clear. The smoke produced by the Taliban’s rockets and demolition charges chokes up the area around the statues as the smoke from the 9/11 aeroplanes billow out from the upper floors. The final explosions and collapse create a huge rolling cloud of debris detritus and dust.

XI Lance Morrow ‘Who’s Art in Heaven’ Time Magazine, 2001. The cultural critic wrote a curiously philistine apologia for Taliban vandalism. He offered the Guggenheim collection to be destroyed as an exchange for the Buddha statues. Morrow’s contempt for modernist painting a sculpture may have extended to the forms of modernist skyscrapers like the WTC, but I doubt he would run the risk of professional suicide—post 9/11—to say out loud that the Taliban should again immolate anything in America. Morrow offensively stated: ‘we might have donated millions of hip-hop lyrics to the Taliban’s guns and mortars, and thrown in the porn channels. We might have rounded up every surviving video of “Dances With Wolves.” We could have turned the Guggenheim and Whitney museums upside down and shaken them lightly, and—to the net gain of civilization—offered up dozens of works to the Taliban’s immolation. We might have offered up Marilyn Manson, Howard Stern, Regis Philbin and the entire XFL.’ time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,101444,00.html. Was the commentary an indiscrete invitation to the mayhem of 9/11? Would the world be better if the Guggenheim collection was burned and the building turned upside down?

XII When the monuments at Bamiyan were destroyed, I was employed at the UCLA Hammer Museum in California. The director Annie Philbin, passed around a petition for employees to sign condemning the demolition and appealing to the US government to intervene. Nothing came of the appeal and there is regret for neglecting the warning signs.

XIII W.L Rathje ‘Why the Taliban are Destroying the Buddhas’, usatoday.com/news/science/archaeology/2001-03-22-afghan-buddhas.html, Stanford University lecturer and Discover Archeology Magazine Editor.

XIV Ibid.

XV Donald Rumsfeld ‘DoD briefing with secretary Rumsfeld and Gen. Myers,’ defenselink.mil/transcripts/2003/tr20030411-secdef0090.html, 5 June 2005. His famous remark that ‘Stuff happens’ was in response to hostile questions about looting in Iraq under the nose of US troops. Rumsfeld essentially repeats Morrow’s casual disregard for cultural treasures and the breakdown of order of which vandalism is an early symptom. The casualness of the remark betrays a detached attitude about law and order in a state that is supposed to undergo ‘nation building’ and re-enter the community of democratic nations. Likewise, the piratical looting of Iraq’s museums alerted curators to very troubling developments in the war long before the Pentagon realized—ordinary criminal gangs proved ready to prosecute the war more ruthlessly than either the coalition or the insurgency. Most of the killing (about 10,000 dead civilians) since the invasion have been carried out by freebooting gangs of thieves operating for profit motives in the same manner as the initial looting; not part of either a religiously inspired Jihad or a nationalist rebellion. Essentially, a series of tomb robberies triggered a killing spree that has not begun to abate. Martin Van Creveld’s thesis that loosely organized criminal gangs would come to dominate the act of killing in warfare has been achieved in Iraq and the first signs of this domination were conspicuous during the looting of precious artifacts.

Social Media Photography: Snapchat 10-Second Images by Amanda Leigh

1 Second: Snapchat #Notes

Instead of passing notes in class, you send your friend a Snapchat image, mobile to mobile. By time your teacher interrogates you, the note has disappeared. You insist, “I wasn’t texting: I was only using my calculator.” Your teacher replies, “Weird that you use your calculator in English class.” As a rule, she only calls you out on this one time per class, and ignores the other twenty Snapchats you send within the hour. Favorite Snapchats this hour: 10-second Snapchat of the clock, with the second hand slowly ticking by, and 6-second Snapchat of best friend trying to stay awake during lecture. #DisappearsInSeconds

2 Seconds: Snapchat #Kisses

A lonely night on Twitter and all you want is a good-night kiss. Ask your followers to Snapchat you a kiss. You might be surprised at what you get. After all you don’t even know your followers’ real names, ages, genders or sexual orientations. I guess it doesn’t matter as long as you aren’t too judgmental. Although these are temporary kisses, just to hold you over for the night, you might want to save some for later. Hurry and take a screenshot of the images as fast as you can. Make a picture collage of all your #TwitterLove.

3 Seconds: Snapchat #Sexting

Beware of sexting while drunk. Just because it’s over in ten seconds doesn’t mean it’s a safe bet. Images pass fast through social media, from Snapchat to Twitter to Tumblr to Facebook. Then all of a sudden your boss and your co-workers have a picture of your penis on their laptops or Smartphones. Who cares if half the team has already seen your super powers and the other half still wants to. That’s not the point. The point is that you want to be in charge of who views your Snapchats – don’t give your trolls, stalkers or archenemies the power to control you. #NotSoSexy

4 Seconds: Snapchat #SexSpam

Nothing sexy about sex and spam – in fact it can leave a bad taste in your mouth. Maybe you enjoy a full-figured woman with a sandwich made in between her jumbo-size buns; but different people have different tastes. Even a temporary 10-second image permanently scars an impressionable young mind. The image disappears but the impact lasts a lifetime. Easy to say just don’t open it – but who knows what’s behind the screen. Maybe it’s something you absolutely must see. #TooTempting but #DontOpenIt!

5 Seconds: Snapchat #Warnings

#Hilarious! Snapchat.com issues an advisory to users about graphic content, nudity, sexting, profanity and other general vulgarities epidemic in social media. #NewsFlash Snapchat – all your users have been on the internet 10 times as long as your product and 2 times as long as your thirty-something hipsters. Your target audience creates all this content you warn about. Funny that the advertised age for Snapchat is 17+ when the ideal age to explore social media platforms seems to be about 13.

6 Seconds: Snapchat #Trolls

Does everyone on social media have a handful of trolls? Or is that just a myth? Think about it. It’s kind of nice to have a few trolls who read every single tweet you post on Twitter, follow you on Tumblr and like all your Facebook photos. Who else loves all your Instagrams instantly? Snapchat offers pros and cons for trolls. #ProsForTrolls – if they troll you every single second they don’t even need the full 10-seconds to catch your Snapchat and freeze it in a screenshot. #ConsForTrolls – they only have access to your Snapchats shared through other social media, not those you send directly mobile to mobile.

7 Seconds: Snapchat #Stalkers

Can you even imagine being a contemporary stalker who is not tech savvy? The modern day stalker perfects both his – or her – social media and hacking skills. If your stalker gains access to your email, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and other social media accounts, why should Snapchat be off-limits? Sure the 10-second maximum is torture but most stalkers don’t mind a challenge. Snapchat offers pros and cons for stalkers too. #ProsForStalkers – background details in the Snapchat image give away your exact location. #ConsForStalkers – they only have 10 seconds to figure out where you are. On the other hand, if your stalker has your mobile number or access to all your social media accounts, he or she can send you some fun Snapchats – by your window, at your car, inside your house. #Madonna A Snapchat disappears in seconds but the anticipation never does.

8 Seconds: Snapchat #Murder #Suicide

Suicidal Snapchats instantly scare the sh*t out of your captivate audience. After all, you choose who to send the Snapchat to – mobile to mobile or through other social media platforms. You control who can open it. You set the timer and decide how many different images to send: 2-second image of a razor blade, 2-second image of a white tile sink, 2-second image of blood drops on the white tile, 2-second image of a cut wrist, 2-second image of the word “HELP.” 10 seconds of terror sent in 5 Snapchats. Imagine the fun images that a murder/suicide inspires. As with all social media, you know some #TorturedSouls use Snapchat to gain maximum attention.

9 Seconds: Snapchat #CrimeSpree

#BreakingNews Criminal snapchats himself robbing a bank – then sends it to the police to taunt them. Bank robber returns to rob the same bank three different times. He takes the same selfy at the same spot near the vault each time. This final time, police send him their own Snapchats back instantly: 6-second image of his vehicle license plate, 4-second image of his driver’s license picture, 2-second image of the police squad as they surround the bank. His biggest mistake – stops to check Snapchat as he robs the bank. #StupidCriminal or #WantsToGetCaught!

10 seconds: Snapchat #LifeSpan

Snapchat images theoretically disappear in a matter of seconds, from 1 to 10. Snapchat’s creators expected a Snapchat to reach its maximum lifespan and then simply to expire, to vanish, to disappear. Snapchat apps include technology to prevent saving a Snapchat on your phone or computer. But you can simply take a shot of the Snapchat image on the screen with other software. The idea of disappearing Snapchats encourages many users to take spontaneous, uncensored selfies and share them freely without concern. In reality the images don’t always disappear.

Once you capture a #SnapchatScreenshot, the image lasts forever – on your phone, your computer, your social media accounts and potentially any social media platform throughout the world. It takes a lifetime to see if your Snapchats reappear.

Photo credit (in order top to bottom): technologystory.com, Mike Paterson, Eltpics, Daelynn Busch, Daelynn Busch, Snapchatted.com, ehotmusic.blogspot.com, snapchatted.com, Venturebeat, Shuttle stock, @violentacrez, Rex via madonnafansworld.over-blog.com, Rex via madonnafansworld.over-blog.com, turbosquid.com, Raisa Photography, cinemateaser.com, sofiaecho.com, The Verge, beccaxanne08

fulcrum by Ross McDonnell

Bodyswap by Kim Seymour

Bodyswap is a story, an archive, a performance, an artwork. What you are looking at in the Isolation Room is something quite extraordinary – an allegorical but simultaneously real and authentic account of the meeting of two similar, very different women in the famous city of Oxford. One of the two women is the artist: young, pretty, vivacious, ambitious, compassionate. The other is a prostitute: young, pretty, damaged, and derailed by drugs – yet also retaining, against the odds, a degree of compassion. Bodyswap results from an unlikely and hardwon empathetic encounter between the two. Vividly aware of the Biblical resonances underpinning her practice, Kim Seymour entered into a difficult exchange: the prostitute used the artist’s lipstick to scrawl her feelings about plying her trade in the sordid underbelly of the City of Dreaming Spires, writing directly onto the artist’s skin. In an act of surrogate redemption, the artist then laboriously removes the lipstick, smudge by smudge. In a literal and a metaphorical sense, she takes on and then purges her skin of these traces, these stained thoughts and painful memories. It is the act of this exchange that constitutes the artwork and now you, the viewer, are embarking on another exchange, here in this room, giving some of your time and attention to contemplate what might otherwise go unnoticed, hidden in the shadows. In return, Kim Seymour, and her collaborator, give you their bravery, their insight and their compassion. Bodywap warrants and rewards your attention.—Paul Kilsby, Oxford 2012

Isolation Location by David Johnson

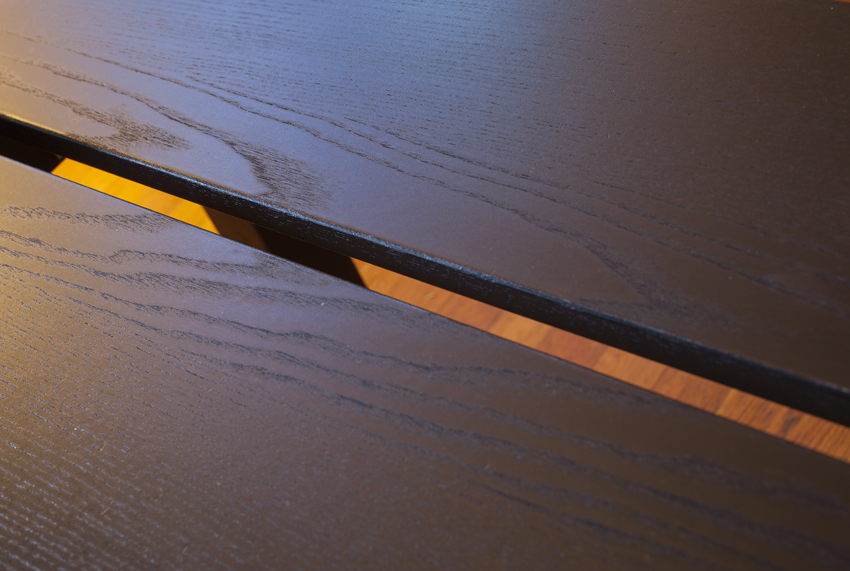

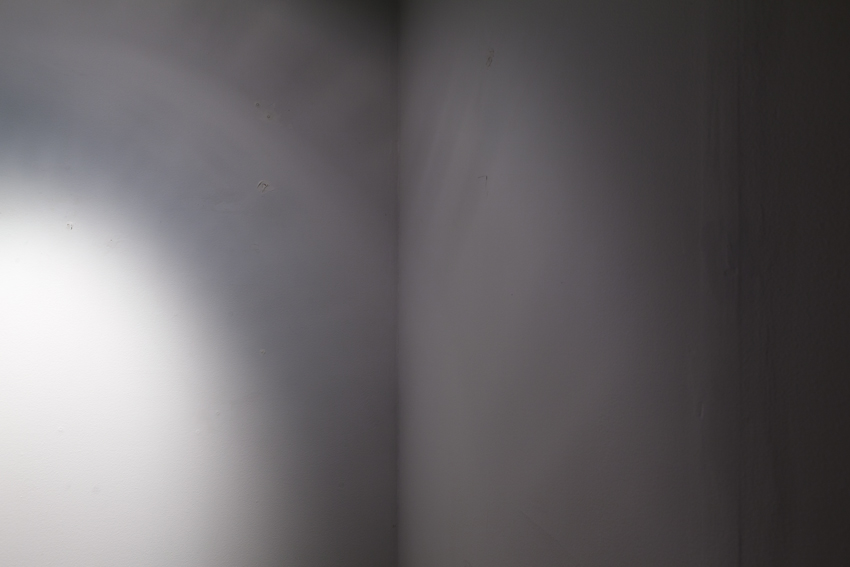

My artwork examines the concrete intersections of society, architecture and the individual. In my process, I search for revealing details within the commonalities of everyday man-made environments, as I examine domestic, office and exhibition spaces. These photographs are organized abstractly with plays between volume and surface. The images are meant to create a sense of instability in perceived ideas of self and place for the viewer.

“Location Isolation” is a photographic series that documents the Isolation Room/Gallery kit in its established setting as an apartment gallery in Saint Louis and then presented in a pop up exhibition in Copenhagen. These images depict bare walls of the gallery and the surrounding domestic situation just beyond its temporary walls. Scarred with screw holes from past installations illustrates the history of space, while the transition from cool day light to warm artificial light of the gallery creates a tonal shift. The details of the space, which exist below the viewer’s threshold, are abstractly composed within the camera. The subjects in the photographs fluctuate between vaguely suggestive and quietly unsettling.

ALL IMAGES: Institutional Etiquette and Strange Overtones, 2011-2012

I Feel Like the New Bridge: A Geo-Historical Analysis Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s, “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped,” 1975-85 by Megan Koboldt

“Never did anyone look at the Pont Neuf as much as the day it was hidden… Christo teaches us to see.”—Jack Lange, Minister of Culture. (I)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s site specific and temporary installations both in the public environment as well as with in the confines of the gallery provide a tactile, accessible experience for the general public. The work is universal in appeal, but it often raises heated questions about the use of public space and objections from authorities and their constituents. Site installations provide the viewer with a different visual experience that transforms and transcends expectations so that landmarks are viewed as art objects instead of mere tourist destinations. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installation, “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” 1975-85, creates an immediate accessible entry way into French Renaissance history and contemporary French politics on an epic, massive scale. “Le Pont Neuf” itself is an iconic symbol of French political and religious unity and Christo and Jeanne-Claude appear to be using the forms and cultural/historical associations of the bridge to comment on and even heal political turmoil suffered in France during the 1960’s and 1970’s.(II) The wrapping itself becomes a metaphor for building society together through art.

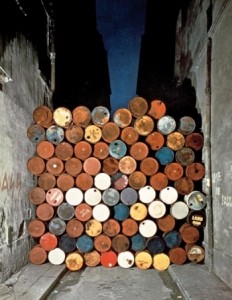

In the 1960s Christo and Jeanne-Claude began wrapping objects during a time in Europe when France was wracked with conflict.(III) Many of their early installations, “Stacked Oil Barrels and Dockside Packages” 1961, “Wall of Oil Barrels- The Iron Curtain” 1961-62, “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” 1975-85, and “Wrapped Reichstag” 1971-95 often reference political conflict and unrest spread throughout Europe; the beginning of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Export Countries), division and creation of the Berlin Wall and the social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s. Each temporary installation altered the entire space, altering aesthetic quality uncommon in public art, and giving the work a life of its own. “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” is one of the artist’s most notorious installations that took the artists ten years of bureaucratic negotiations, arguments, and approval to finally make a reality.(IV)

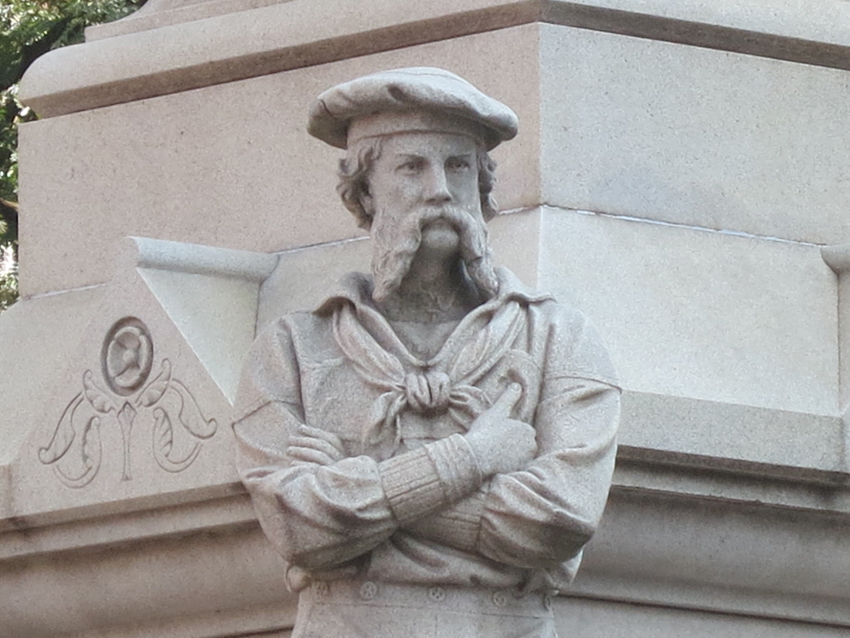

The 405-year-old “Pont Neuf” stands as Paris’s oldest bridge, taking a central part in Parisian culture for centuries. Its birth spanned three decades of political unrest and religious turmoil, a period to which the bridge is associated with today.(V) Henry IV, or Henry of Navarre, became king bringing religious and political harmony back to French citizens after years of war between the Catholic and Huguenot sectarian factions. Henry IV’s was admired by the French and his political leadership skills have been carved into history through the designs and life of the Pont Neuf. His signature equestrian statue still stands upon the bridge, in remembrance of Henry but also as a symbol of the unity the bridge brought to the people, a symbol for them to evolve and rise up from inequality and hate.

The construction of the bridge is continuous. Over time each stone and arch has been replaced and preserved by many generations. The original design by Jean Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau, was completed in 1607 under Henry IV’s direction and supervision.(VI) He promoted agriculture and education, regularized state finances, and encouraged the arts; the “Pont Neuf” embodies much of his reforming zeal. Henry’s stabilization of France gained long lasting respect in France and this is manifested on the “Pont Neuf” with various monuments to Henry.(VII)

Stretching across the Seine River, “Le Pont Neuf” reaches 761 ft. in length 72 ft. wide, connecting Parisians to the Ile de Cite, the ritual city of Paris. Composed of two separate spans, one of five and the other of seven arches, joining the left and right banks of the river together. (Op. cit., Volz, pg. 13.) In the present era, the bridge is still used as a prime source of transportation, inviting the public to interact with it regularly as pedestrians, commuters and site seers. The Ile de Cite is a natural island of the Seine River, housing “Notre Dame” cathedral, “The Daulphine palace,” “Prefecture de Police,” “Palais de Justice,” and Hotel Dieu hospital-the administrative ecclesiastic beating heart of France itself.

The visual impact of “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” interrupted the normal state of the bridge. The wrapping process reveals geometric shapes and angles that symbolize the idea of a bridge which connects geographical units and peoples. It is tempting to see Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s habitual process of wrapping and covering objects like “Le Pont Neuf,” as if they are conserving and healing the object. The selection of the object and technique of the wrapping transforms the outside environment into an over-sized blank canvas, transforming the functional architecture into an object of contemplation, as well as a novel re-interpretation of the original purpose of the structure. The created drapery idealizes the bridge and the act of draping is referred to in Hegel’s theory of aesthetics as important.(VIII)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s use of the silk-like polyamide material heightens the lines and shape features of the bridge. The fabric creates a pleated texture pattern in the wrapped piers and capitals. The fabric gathers to accentuate points on the bridge, like separating couture design with elegant proportions into smoothly draped sections that define the curvilinear silhouette of a feminine figure. This organizes the architectural elements of the platform and the arches into a symmetrical, stretched structure that unifies the engineering and the ornamental features of the bridge, bringing out the forms and hiding the blemishes. The shiny polyamide fabric heightens the eye-catching element of the arches and piers, tricking the eye into seeing an almost cylindrical shape. The crowns of the columns extend and drop to a lesser circumference at the base making the outline of the bridge flow in a smooth manner from the top into the river below. The formal elements of “Le Pont Neuf’s” cylindrical piers, circular capitals and smooth arches give the whole composition a clean and organized yet liquid metallic outline. The light posts, banisters, and equestrian statue wrapped together form an enormous, temporary form.

The material was appropriate for the “city of light,” creating a variety of light effects. The sand colored metallic fabric interacted with the outside environment in a variety of ways during different times of the day. Daylight kept the liquid look of the fabric at bay, almost making the wrapping look similar to muted sand stone. During the night hours, “Le Pont Neuf” became illuminated with amber light that transformed the surface revealing a feminine hourglass figure. The lighting element of this environmental installation highlights the symbolic and transformative effects on the structure of the bridge. “Drapery enhances the organic beauty of the form, idealizes it, and hides its imperfections. The focus on the form within, not the ornamentation itself.”(IX) The use of a public space and drapery allows the viewer to interact with the piece from different angles and perspectives, transforming the view of “Le Pont Neuf” into an unfamiliar and new structure, potentially even changing the perception of the bridge long after the wrapping is removed. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s works are temporary but the memories often remain for years.(X)

The wrapping, along with the rope and construction constitute the many elements of connective signs that makes the piece an organic form, containing a skeletal structure, ligaments and muscle. The underlining engineering of the bridge form the bones, the ropes resemble tendons and ligaments, and the fabric stretches over the whole to become the skin of the bridges new sculpture. The ropes or ligaments, accentuate the capitals separating the piers into defined almost anatomically, but also unites the wrapping to the bridge. The overall composition unites the Seine River and “Le Pont Neuf” optically. The reflection of the structure on the shimmering surface of the river shows how the installation changes the entire environment around it. Christo and Jeanne-Claude are highly sensitive to the wider environment. The reflection of the structure not only reflects the image but also represents why Christo and Jeanne-Claude chose “Le Pont Neuf.” The wrapping is effectively a cast, molded specifically for “Le Pont Neuf” and its viewers. Perhaps this “cast” tells us something about France after the post-colonial and civil strife of the 1960’s and 1970’s and can be seen as a continuation of the original “Le Pont Neuf’s” intent to bind French society together through art. The reactions to the work were often quite outspoken and became part of the work.

“Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” has been compared to a body by other writers in the context of superficial fashion, both discuss the wrapping as a direct relation to the function of clothing being a boundary between the intrinsic self and body it surrounds and the outside world. Salinger discusses how unique “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” was and cannot be discussed easily without talking about the bridges connection to Paris and its public identity. Dress (or wrapping) becomes a part of the creation of identity, linking the biological body to the social, going from private to public. Acting as the mirror to hold up the psychological shaky self, constantly being redefined in light of its reflection in society however this comparison to the body brings up the issue of wrapping as protection, clothes, even fashionable ones are a way to protect the body. (Op. cit. Salinger, 7)

This reading of the wrapping’s protective process is especially pertinent in the context of the French phrase: “I feel like the Pont Neuf” “comme Pont Neuf” which can either mean “I feel at death’s door” or “I’m mended.” The wrapping becomes a cast. Every French person understands that death and regeneration are referred to in this one phrase with a double entendre that uniquely refers to this bridge and the ongoing process of repairing the bridge stone by stone. Christo’s motivation for wrapping the bridge is not dissimilar to the care and attention the bridge regularly requires anyway. The wrapping process and exhibition which lasted for only 14 days directly references both this process of continual repair and regeneration as an extension of the life of the body of the bridge itself and in the linguistic meaning of the French phrase. One Parisian even spent so much time “feeling” the bridge by lovingly running her hands up and down the fabric that she forgot she was still on a functional bridge and she was run over by a car. In her particular case she took the idea of “feeling like the bridge” literally.

Shortly before Christo and Jeanne-Claude created this installation, France was recovering from the Vichy period in WWII, the Indochina war, and the more recent Algerian conflict.(XI) Ten years after WWII ended, the Algerian revolution began, bringing France itself to the brink of civil war. Civilian and military forces on both sides, clashed in the streets eventually leading to the independence of Algeria and the fall of the Fourth Republic of France. Charles de Gaulle,(XII) a retired French military officer, founded the Fifth Republic of France which restored order and began a new era of restoration and growth. The wrapping process as used by Christo and Jeanne-Claude obliquely refer to the national healing process, it is no accident that “Le Pont Neuf” was chosen as the site to wrap.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s choice and placement of the wrapping on “Le Pont Neuf” illustrate an intention: “The concealment caused by the fabric challenges the viewer to reappraise the objects beneath and the space in which it exists.”(XIII) “The artists thought it was innovative to wrap up the Pont-Neuf. But they weren’t aware that for many centuries its stone arches had been enveloped in the folds of Parisian institutions, without which it would have collapsed a long time ago.”(XIV) This, along with a variety of different pieces of information, comments on how “Le Pont Neuf” is in itself a living being within Parisian culture. That it is passed down through generations and has ownership over the people of the city and the people of Paris have ownership over it. The never-ending access to the bridge any time of day, gave artists the opportunity to interact with a larger audience and provide the viewer a renewed experience of the iconic bridge through simplifying the aesthetic qualities. The wrapping hid the bridge’s identifying features which left the installation room to wipe previous perceptions of the bridges slate clean and metaphorically mend the cracks made during the wars. (Op.cit. Latour and Hermant, 99) These sorts of intentions are denied by Christo and Jeanne Claude as they claim the wrapping is just an aesthetic exercises. However their other alterations with monuments are quite telling.

Through the act of wrapping, a metaphor for French society, Christo and Jeanne Claude’s installation connects with the fundamental idea of Henry IV’s “Le Pont Neuf,” binding society together and healing scars. Christos intent can be seen not only with “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped,” but also the “Wrapped Reichstag,” 1971-95. The Reichstag was built in 1894, destroyed by arson in 1933,(XV) almost destroyed in 1945 and restored in the 1960s, has become a symbol of democracy denied.(XVI)The destruction of the Berlin Wall and reunification of Germany allowed Christo and Jeanne-Claude to realize the project to wrap the building with a protective layer of fabric that brought awareness and importance to the democratic icon in Germany and the world.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s universal appeal has brought attention to not only the use of public space but also has transformed landmarks like “Le Pont Neuf,” into contemporary art works that bring value to public art. The creation of “Le Pont Neuf Wrapped” shows the many layers of the artists love story with not only each other, but within art. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s experiences through their childhood, Christo’s Bulgarian citizenship being stripped away and Jeanne-Claude’s experience as a military child. The refugee of the Cold War heading west to freedom and the child of a military officer make a symbolic cast over the bridge that unifies the personal and historical relationship.(XVII) Jeanne Claude is a daughter of the French establishment and Christo is an adopted son.(XVIII)

The wrapping’s massive scale and epic 14-day installation revealed a unique point of view about Paris and its historical identity. The whole environment around “Le Pont Neuf” changed and brought awareness to the parallels between the past and present. Residents and visitors from all over the world were prompted toward introspection, contributing to a legacy that still is associated with the bridge today. Jeanne-Claude commented on their work that:

“The temporary character of the work of art creates a feeling of fragility, vulnerability, and an urgency to be seen, as well as a presence of the missing, because we know it will be gone tomorrow. The quality of love and tenderness that human beings have towards what will not last, for instance the love and tenderness for childhood and our lives, is a quality we want to give our work.(XIX)

The juxtaposition of permanence and temporal almost seems as if it is the true subject of the duo’s work. The importance of conserving “Le Pont Neuf” and the love of the “what will not last” shows the transformation of “Le Pont Neuf” from a bridge to a living, breathing body.

Notes

I Jack Lang was the Minister of Culture in France during 1981-86 and 1988-1992. Credited for creating the “Fete de Musique,” a massive celebration of music held annually on 21 June. Created the Lang Law, allowing publishers to enforce a minimum sale price for books. Lang commented on the Maysles Brothers film, Christo in Paris, 1986.

II France experienced a period of civil infighting and military operations from 1562 to 1598, during which Catholic and Protestants fought over factional disputes between the house of Bourbon and the house of Guise. The Saint Bartholomew’s Massacre occurred on the wedding day of Protestant Henry of Navarre and Catholic princess Marguerite de Valois. Killing spread over the next five days and eventually to other cities. The 1960’s were marked by various civil and societal upheavals notably the riots of 1968 and the turnover of the republics (Baird, 426-494).

III Rabia Bekkar, “Algerian War of Independence,” p. 136-138.

IV Volz, Wolfgang et. Al. “Christo: the Pont Neuf Wrapped,” Paris, p. 11.

V Henry IV became king of France in 1589-1610. Originally, Henry of Navarre, a relative of the Protestant House of Bourbon, a royal French family. When Henry III died, Henry of Navarre became king and ended the War between the Huguenot’s and Catholics. As Catholicism the traditional religion of France, Henry gave freedom to Protestants by enacting the Edict of Nantes (Holt, p. 153-189).

VI Whiteney, “Bridges of the World: Their Design and Construction,” p.135-138.

VII De la Croix, “The Lives if the Kings and Queens of France,” 175-182.

VIII Inwood, “Introductory Lectures on Aesthetic,” 146-49.

IX Salinger “The Pont Neuf Wrapped: Framing the Bridge, Bridging the Frame,” p. 10-11.

X Many political advisors were against the public monument, thinking that the public would not believe that the project wasn’t from tax payers rather than the artists themselves. Claude Pompidou, wife of former President George Pompidou, being a friend of Jeanne Claude, sent letters on behalf of Christo and Jeanne Claude to Jacque Chirac for installation approval. Chirac absentmindedly signed the approval after an assistant secretly slipped the form within a stack of papers (Volz, et. Al.,

p. 120).

XI Vichy was a regime of French government that aided Axis powers in WWII. Marshall Philippe Petain, lead the group who assisted the German occupying forces in getting rid of Jewish citizens and other “undesirables”. ( Bekkar, 137)

XII Charles de Gaulle was a decorated French Military officer who served in WWI and WWII and later became President of France after the fall of the fifth republic in 1958. (Spartacus, 2012)

XIII Adam Thomas Blackbourn, 2011, quoted on Christo and Jeanne Claude’s site

XIV Bruno Latour and Emilie Hermant Paris and its ownership in, Paris: Invisible City. Latour is a French sociologist and Hermant combined words and images to capture all of Paris in a single glance, which is said to be impossible to the point it becomes invisible, p.99.

XV The Reichstag is now the German Parliament building in Berlin. During WWII the building was unoccupied due to the dissolvent of Parliament and the 1933 fire that was set after Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. No one knows who set the fire. In any case it was a symbol of failed German Democracy. (Christo and Jeanne Claude, 2012)

XVI “Wrapped Reichstag,” Christojeanneclaude.net

XVII Jeanne Claude was the daughter of, Major Leon Denat. During WWII. She was sent to live with her grandparents due to one in the military and the other involved in the French Resistance. (Christo and Jeanne Claude, 2012)

XVIII Christo and Jeanne Claude were both born on June 13, 1935. Christo was born in Bulgaria and Jeanne Claude born in Casablanca, Morocco. They met in 1958 in Paris, France. Jeanne Claude graduated from the University of Tunis in 1956 with a Baccalaureate in Latin and Philosophy. Christo went to art school in Sofia, Bulgaria at the Fine Arts Academy and the Fine Arts Academy in Vienna, Austria. In 2009, Jeanne Claude passed away due to a brain aneurysm. (Christo and Jeanne Claude, 2012)

XIX Newman, “Christo and Jeanne-Claude Unwrapped.”

Sources

Baird, Henry Martyn, “History of the rise of the Huguenots of France,” NY: AMS Press. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22762/22762-h/22762-h.htm, 1970.

Barnes H. “Wrapping Up the Story of Artist and Paris Bridge.” St. Louis Post – Dispatch: Pulitzer, Inc.; E3,1991.

Bekkar, Rabia, “Algerian War of Independence” in the “Encyclopedia of Modern Middle East and North Africa,” edited by Phillip Mattar, Mcmillian Reference USA, 2004.

“Charles de Gaulle” spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/2WWdegaulle.htm. Accessed November 2, 2012

‘Christo and Jeanne-Claude’ accessed on October 1, 2012, christojeanneclaude.net

de La Croix, René, Duc de Castries, “The Lives of the Kings & Queens of France,” Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1979.

Grande, John K., “Christo and Jeanne-Claude: World Wrap.” Vie Des Arts, p. 48.

Guthmann , E. ‘Christo in Paris’ by Maysles Brothers, San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco, CA: Hearst Communications Inc., Hearst Newspapers Division; 1991:E3

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Freidrich, “Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics,” 1993. Trans. Bernard Bosquet. Ed. Michael Inwood. London: Penguin books,1993.

Hoelterhoff, Manuela, 2009.” Jeanne-Claude—Christo’s Dynamic Muse” Bloomberg, November 20, 2009. (accessed Nov. 21, 2012).

Hogue, Martin, “The Site as Project: Lessons from Land Art and Conceptual Art.” Journal Of Architectural Education, 57, no. 3 (February, 2004).

Holt, Mack P., :The French wars of religion,” 1562-1629. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press,1995.

Latour, Bruno and Hermant Emilie, “Paris: Invisible City,” France. bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/downloads/viii_paris-city-gb.pdf

Newhouse, Victoria, “Art and the Power of Placement,” NY: The Monacelli Press Inc., 2005.

Newman, Cathy, “Christo and Jeanne Claude Unwrapped” National Geographic, November 2006. (accessed December 10, 2012). ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0611/voices.html

Salinger, Victoria, “The Pont Neuf Wrapped: Framing the Bridge, Bridging the Frame.” PH.D Diss., Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, 2007.

Thomas, Selma, “Media Review,” Curator, 44, no. 2, 2001.

Vaizey, Marina, “Christo,” New York: Rizzoli, 1990.

Volz,Wolfgang, David Bourdon, Bernard de Montgolfier, and Eric Himmel,1990. “Christo: the Pont-Neuf, wrapped, Paris, 1975-85,” New York: H.N. Abrams.

Whitney, Charles S., “Bridges of the World: Their Design and Construction,” Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. 2003.