Ain’t No Love In The Heart Of The City by Daniel McGrath

Mankind which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympic gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction with as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.

Artists depicting war and its terrifying consequences are not afraid to hold a mirror to the darker side of human nature, exposing the fears and irrationalities that drive us on to obliterate and damage the lives of other human beings. Shomei Tomatsu’s image of a Hiroshima victim’s hideous scars is a reminder of the twentieth century appetite for killing on a grand scale. Every living person looking at this image must realize that: ‘he too is a “human negative” waiting to be processed.’(II) Tomatsu’s photograph is an intimate portrait of suffering. Other paintings and sculptures like Picasso’s “Guernica” (1936) that depict war are considered masterpieces of civilization. Arguably, modern societies are better educated about the consequences of wars today, as a result of omnipresent electronic imagery than the generation that produced Picasso.

As Walter Benjamin spells out though, rather than sensitize us to suffering, the flood of imagery may be one of the factors contributing to the opposite effect—leaving people alienated and violent.(III) The ‘War on Terror’ itself increasingly seems to be dictated by the characteristics of electronic and photographic imagery. Indeed, with recent events in Boston in mind, it is the photographs we associate with current events which are becoming defined by neologisms and new-fangled technological “meta” issues. By pushing the button that exploded the bombs the Tsarnaevs started a media machine.

“Crowd Sourcing” is the newest trending technique whose reputation has risen and fallen with the 24-hour news cycle. It is an online, distributed problem solving and production model, often used to attempt to solve crime via the analysis of publicly available forensic evidence, such as the meta-data contained in imagery and embedded computer code. The coordinates N 42° 20’ 56.871”, W 71° 4’ 51.3804” logged onto the meta-data of Tweets and photographs became critically important for the pioneers of this brave new research model. Even responses to the bombing via Twitter were mapped with geo-tagged references to “#boston,” whose frequency correlated with distance from the bombing. Amateur detectives began to pour over data to identify potential bombers. Most of the identifications proved to be spectacular errors that caught runners and various onlookers in the dragnet. The reality was more prosaic—a pair of inconspicuous brothers casually walking along the pavement gradually emerged as suspects.The map of #boston is dry stuff, but according to the blogger of Floating Sheep: “This analysis shows how established spatial patterns of place-based social media activity can be disrupted by extraordinary circumstances, such as a terrorist attack, as well as the importance of looking at how such spatial patterns change over time.” To what purpose this is useful, be it commercial or social, remains to be seen.

Twtter and Hashtag arrays in the wake of the Boston marathon bombing. Source www.floatingsheep.org/2013/04mapping -boston-bombinh.html

However, every act of terror is registered, analyzed, and narrated by the media which is rapidly automated. In addition to the geekier reaction there was a great deal of juicer tattle from social media. Once the suspects were identified, short fictions about the suspects worthy of Jackie Collins were immediately written. Even the turgid romance writer, Barbara Cartland, called Collins’ work “nasty, filthy and disgusting.” Her best selling book, appropriately enough for this comparison The Love Killers,1989, depicts a very public assassination in Central Park. She magazine called it “Sensational, bitter, completely compulsive…” The ravenously obsessed Tsarnaev fan club takes Collins’s pornographic aesthetic to the edge and crosses right over it. The following is not an excerpt from a Collins novel but Tumblr account Free Jahar! which is devoted to the alleged angel faced assassin:

[Dzhokhar] sounded much more terrified than you could have possibly been. “Are you okay?” You begged him to tell you he was fine, nobody really knew. “I’m hit, in the leg, but I- wait what? You’re asking if I’m okay?” He was surprised, but calmer now. “I know you didn’t do it, and even if you did, I know you aren’t harmful.” He sighed with your words, he felt safe for the first time since he saw his face on the television.

At first most reporters hoped the Boston Bombers were Tea Party Rednecks, or, according to Reddit “Crowd Sourcing” sleuths, a variety of assorted middle-aged paunch-bellied losers or a Saudi overstaying his student visa. Sadly no, behold the face of terror ye mighty and despair! It was Zooey Deschannel’s little brother and his cute floppy hair. What could be more appropriate on the “internets” than a dose of conspiracy theory and breathless porn rolled into one nylon-black-backpack story?

The geo-location devices that enabled investigators to amass the meta-data lurking behind every cell phone snapshot at the finish line of the Boston Marathon didn’t see this one coming: pastebin.com/raw.php?i=1gRSS5ZB wherein 50 Shades of Grey meets Jihad. The outlines of social media and technology are exposed and turned inside out all at once as Dzhokhar, on the run and on the job, turns out to have been hiding away on a porno film set, in the mind of one frenzied fan-girl:

“He kissed your neck, sucking on it to leave his mark, biting down every now and then. When he breathed out you got chills down your spine, making your nipples hard when he squeezed them. ‘Cmon baby, give me something to think about in jail.’”

It’s racy stuff. If you are an aspiring international terrorist it certainly pays to be a cherubic fallen angel, a fresh-faced man-about-town.

Gawker quite neatly cataloged the atrocities on Dzhokhar’s twitter feed: gawker.com/5995065/is-this-the-boston-marathon-bombing-suspects-twitter-account. Dzhokhar chillingly Tweeted Jay-Z/Bobby Bland lyrics after the bombing and before his capture: “Ain’t no love in the heart of the city, stay safe people” demonstrating a blend of bravado, lyrical obsession and callousness that would make Mark David Chapman (assassin of John Lennon) proud. This is the first large bombing in the US in the age of social media, so the unfolding drama will likely take many more twists and turns in the social-media funhouse. But there is something eerily familiar about the Boston attack. Young men assimilated into western counter-culture like hip-hop, consumer goods like Nike and Mercedes, and foster an interest for the black-flag of Jihad. Here are the coordinates for the first installment of the tragedy part of this repeating history: N 51° 31’ 49.5618”, E 0° 7’ 26.0286.”

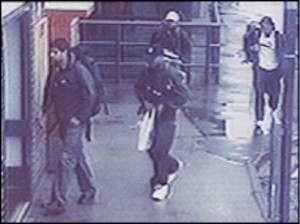

This happened before Twitter. The suicide bombers who attacked London 7 July 2005, looked like ordinary backpackers going on holiday. They were, of course, carrying explosives in their rucksacks. The image of these men casually strolling through the entrance of Kings Cross, one with a plastic shopping bag another with a baseball cap, through the dreary puddles is only made remarkable by the knowledge of the destruction they later wrought. However, the scene’s ordinariness carries its own menace. The fact that the picture appears to be from a security camera implies that a crime is in progress—the picture in its own prosaic dullness carries a sense of threat.

The exchange of violence between al-Qaeda, Iraqi insurgents and the American coalition in the ‘War On Terror’ is often conducted through acts of violence that place a premium on creating or destroying visual iconography. These images are the currency of bloody symbolic exchange. Most of the targets selected by al-Qaeda and its successor groups have little conventional military value, but rich symbolic value: statues, skyscrapers, the London Underground, Bali discotheques, and double-decker buses. Otherwise, they mimic horror films with hostage ‘snuff’ videos.(IV) All bombings directed at familiar tourist destinations and famous landmarks amplify the horror of the carnage. Some targets like the USS Cole or the Pentagon have obvious military value, but against such targets al-Qaeda campaigns of attack have been small, improvised, weak and unsustainable affairs in comparison to the enormous offensives launched by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in WW2. Their operations resemble ‘ghazi’ raids rather than total war, because the attacks are not primarily designed to capture territory, kill key military personnel or even assassinate high profile politicians.(V)

‘CCTV photograph of July 7 bombers entering King’s Cross London underground station,’ Associated Press

According to one British officer in India, the ghazis on the Northwest Frontier were only a small fanatical percentage of an opposing force that normally tended to mix bravery with a highly developed sense of running off before getting killed: ‘But when excited by their ghazi brethren, elated by success, they are resolute and bold…their daring and courage is of the most reckless description.’(VI) The ghazi fought to inspire their more circumspect allies, to instill determination and increase fighting spirit. This is similar to the ‘inspirational’ role that al-Qaeda have self-consciously adopted for their global campaign of terrorism.The bombings they carry out certainly serve as a symbolic rallying point for their less ferocious confederates. The bomb designs themselves are downloaded electronic blue prints. Osama bin Laden is still considered to be a hero in parts of the wider Islamic world and symbol of Islamic resistance to America. Opinion polls indicate he was more popular in Pakistan than President Musharaf (now languishing in jail) and more highly regarded than the ibn Saud royal family in Saudi Arabia.(VII) Because al-Qaeda bombings are symbolic gestures, designed to foster more ‘daring’ in the wider Muslim world, the bombings themselves do not add up to the type of national security threat the military or police are typically designed to combat. The hysteria and city-wide shutdowns surrounding the capture of the bombers in London and in Boston belie the relatively small impact the actual bombs cause. However, bin Laden’s ghazi-like organization has proven to be more resilient than previous opponents of the US Army, like the Axis—surviving everything the coalition has sent for over a decade, and even hitting back in western metropolitan areas long after their own base camps in Afghanistan were overrun and the leaders killed. Like the ghazi, a new breed is prepared to ‘lie concealed for hours in the hope of cutting up and mutilating some unarmed straggler or follower, or better still, shooting some armed man and possessing himself of a rifle which is worth its weight in Silver.’(VIII) Almost all attacks take the form of ambush and massacre. So far their cadre of ghazis remain a force to be reckoned with despite the efforts of conventional strategies.

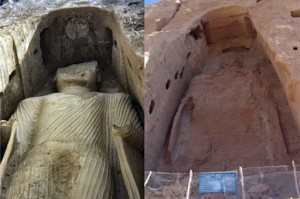

YOUTUBE BEFORE YOUTUBE – BAMIYAN

A key symbolic precursor to the ‘War on Terror’ occurred in February 2001, events whose portentous significance was ignored until the World Trade Center attack on 11th September 2001. Two Buddhist monuments in Afghanistan were gleefully blown up and their destruction broadcast by the Taliban Government of the Emirates of Afghanistan. Appropriately, the attack was carried out on monumental sculpture, for the Taliban were preoccupied with sacred iconography. The Taliban’s official policy toward images remains unremittingly hostile: cameras, advertising and satellite television were ‘banned’ under their laws. Contemporary Muslim societies are saturated with advertising billboards depicting fresh-faced actors endorsing the latest consumer gadgets, figurative paintings of leaders or heroes, and political cartoons in even the most conservative Arabic newspapers. Ancient monuments and archeological dig sites are considered to be the crown jewels of national heritage—the Pyramids and ruins of Babylonian and Roman civilizations are assiduously cared for by governments as diverse as Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Turkey. In spite of this example and the exhortations of other Muslim leaders, the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Omar, decreed the destruction of all statues in Afghanistan, including the ancient sandstone Buddhist statues at Bamiyan. The Taliban stated that:

In the view of the edict of prominent Afghan scholars and the verdict of the Afghan Supreme Court it has been decided to break down all statues/idols present in different parts of the country. This is because these idols have been the gods of the infidels, who worshipped them, and these are respected even now and perhaps may be turned into gods again. The real God is only Allah and all others false gods should be removed all other photographs and electronic images should be likewise forbidden.(IX)

This statement was a declaration of war on iconography—particularly on Buddhist sculpture—but the Taliban themselves filmed the destruction of the Buddha and made the footage available to world media, ignoring their own iconoclastic dictates in order to generate footage that suited their purpose. The destruction can be seen as a warning shot aimed at all prominent buildings or monuments, an eerie foretaste of the collapse of the World Trade Centre in 2001.(X) It’s tempting to categorize it as the prototype viral video.

For many art historians, Bamiyan’s destruction felt like a declaration of war on their profession. Western journalists, however, smirked more often than they condemned. One latter day Savonarola quipped: ‘We could have turned the Guggenheim and Whitney museums upside down and shaken them lightly, and—to the net gain of civilization—offered up dozens of works to the Taliban’s immolation.’(XI) Art world professionals are generally more sensitive to this sort of cultural vandalism than the average western politician or journalist. A curator’s role is analogous to a pit canary in that they are often the first people to smell the poison seeping from the seams of violence.(XII) The public release of the Bamiyan videotape produced a flurry of apprehensive communications between museum directors and within curatorial departments.(XIII) One archeologist even managed to hit upon the “absolute moral superiority” rhetoric of which President Bush and Prime Minister Blair mastered in condemning international terrorism as a new evil a few months later. The statement: ‘any destruction of archaeological remains is an indefensible crime against humanity. I fear archaeological terrorism—this ultimatum of “give us what we want or we will destroy our enemies’ (and the world’s) heritage,”’(XIV) Predictably, however, calls from art professionals to check the wave of symbolic violence went unheeded; the monuments’ destruction was a precursor to when Manhattan’s towering monuments to capitalism were smashed. The looting of Iraq’s museums and archeological dig sites were likewise a precursor of the chaos of an intractable guerrilla campaign and not an example of the progress or ‘messy freedom’ claimed by some politicians.(XV) W.L. Rathje, in another context, of course, could be credited for formulating the Bush doctrine of the War on Terror.

Terrorism literally transformed images into weapons and cameras are themselves detonated like bombs. On Sunday the 9th of September 2001, the veteran commander of the last remnant of anti-Taliban forces in Afghanistan, Ahmed Shah Masood, was giving an interview in the northern province of Takhar to two Arabs posing as journalists. The “journalists” detonated a bomb concealed in their video camera. Masood was killed in the attack. Within two days, passenger jets piloted by terrorists posing as passengers were used as bombs in the most videoed massacre in history. And so it goes… in Boston as, Twitter, Tumblr, Youtube and ubiquitous smart phones act as force multipliers in an escalating tit-for-tat slugging match defined as much by the scars images inflict on the mind as the havoc bombs cause on flesh and blood.

I Benjamin (1936), p. 520

II Ewing (1994), p.238

III Ewing (1994), p.239

IV Nick Berg in Iraq and WSJ reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan were horrifically butchered by al-Qaeda terrorist captors: both murders were videoed and the tapes distributed to Arab news channels like Al-Jazeera or the internet. The beheading video acts as a catalyst for terrorist recruitment, and is a quick and dirty way to scare off foreigners.

V Amer Taheri ‘gazavat’, The Times, 8 July 2005. His suggestion is the most apt comparison to al-Qaeda’s tactics. The historical ghazi carried out hit and run raids on the Islamic frontier, rustling cattle, massacring sleepy farmsteads and villages followed by a quick retreat to the safety of a remote base camp. The modern incarnation of the ghazi in Taheri’s formulation is working toward the re-establishment of the Islamic Caliphate and to subdue the ‘infidel West’.

VI Shadwell (1898) p.318-19.

VII Available from: cnn.com/2004/WORLD/meast/06/08/poll.binladen/. The poll interviewed 15,000 Saudis: conducted by Nawaf Obaid, a national security consultant. Conducted between August and November 2003, after simultaneous suicide attacks in May 2003 when 36 people were killed in Riyadh bin Laden’s popularity took a small tumble. Almost half of all Saudis said in a poll conducted last year that they have a favorable view of Osama bin Laden’s sermons and rhetoric, but fewer than 5 percent thought it was a good idea for bin Laden to rule the Arabian Peninsula.

VIII Shadwell (1898), p. 318.

IX Ibid. p. 411.

X Viewing video footage from the two events a striking similarity becomes clear. The smoke produced by the Taliban’s rockets and demolition charges chokes up the area around the statues as the smoke from the 9/11 aeroplanes billow out from the upper floors. The final explosions and collapse create a huge rolling cloud of debris detritus and dust.

XI Lance Morrow ‘Who’s Art in Heaven’ Time Magazine, 2001. The cultural critic wrote a curiously philistine apologia for Taliban vandalism. He offered the Guggenheim collection to be destroyed as an exchange for the Buddha statues. Morrow’s contempt for modernist painting a sculpture may have extended to the forms of modernist skyscrapers like the WTC, but I doubt he would run the risk of professional suicide—post 9/11—to say out loud that the Taliban should again immolate anything in America. Morrow offensively stated: ‘we might have donated millions of hip-hop lyrics to the Taliban’s guns and mortars, and thrown in the porn channels. We might have rounded up every surviving video of “Dances With Wolves.” We could have turned the Guggenheim and Whitney museums upside down and shaken them lightly, and—to the net gain of civilization—offered up dozens of works to the Taliban’s immolation. We might have offered up Marilyn Manson, Howard Stern, Regis Philbin and the entire XFL.’ time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,101444,00.html. Was the commentary an indiscrete invitation to the mayhem of 9/11? Would the world be better if the Guggenheim collection was burned and the building turned upside down?

XII When the monuments at Bamiyan were destroyed, I was employed at the UCLA Hammer Museum in California. The director Annie Philbin, passed around a petition for employees to sign condemning the demolition and appealing to the US government to intervene. Nothing came of the appeal and there is regret for neglecting the warning signs.

XIII W.L Rathje ‘Why the Taliban are Destroying the Buddhas’, usatoday.com/news/science/archaeology/2001-03-22-afghan-buddhas.html, Stanford University lecturer and Discover Archeology Magazine Editor.

XIV Ibid.

XV Donald Rumsfeld ‘DoD briefing with secretary Rumsfeld and Gen. Myers,’ defenselink.mil/transcripts/2003/tr20030411-secdef0090.html, 5 June 2005. His famous remark that ‘Stuff happens’ was in response to hostile questions about looting in Iraq under the nose of US troops. Rumsfeld essentially repeats Morrow’s casual disregard for cultural treasures and the breakdown of order of which vandalism is an early symptom. The casualness of the remark betrays a detached attitude about law and order in a state that is supposed to undergo ‘nation building’ and re-enter the community of democratic nations. Likewise, the piratical looting of Iraq’s museums alerted curators to very troubling developments in the war long before the Pentagon realized—ordinary criminal gangs proved ready to prosecute the war more ruthlessly than either the coalition or the insurgency. Most of the killing (about 10,000 dead civilians) since the invasion have been carried out by freebooting gangs of thieves operating for profit motives in the same manner as the initial looting; not part of either a religiously inspired Jihad or a nationalist rebellion. Essentially, a series of tomb robberies triggered a killing spree that has not begun to abate. Martin Van Creveld’s thesis that loosely organized criminal gangs would come to dominate the act of killing in warfare has been achieved in Iraq and the first signs of this domination were conspicuous during the looting of precious artifacts.

Tags: Journal