Weaving Through The Street by Emily Stremming

What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially. —Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography

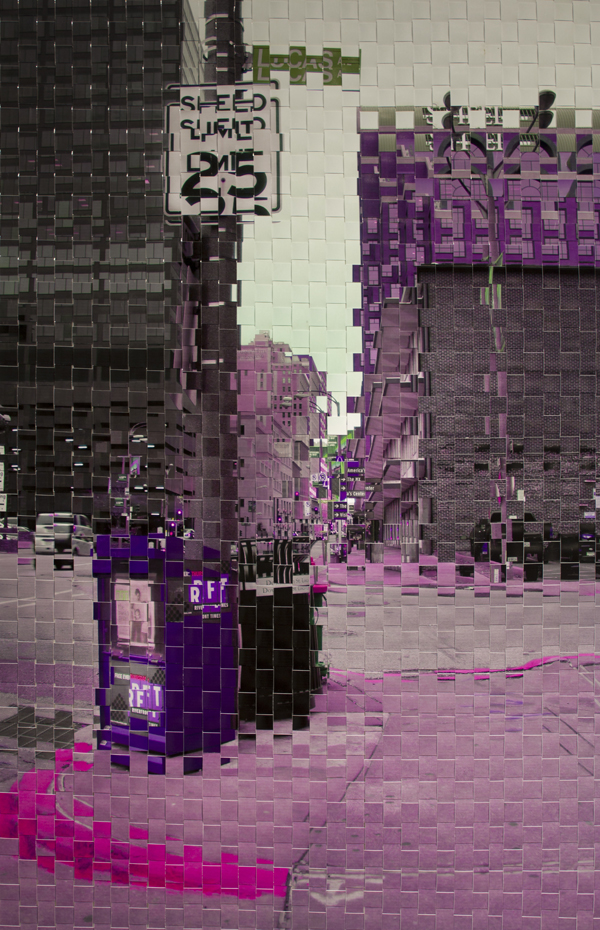

Emily Stremming weaves together photographs of specific mapped locations in St. Louis, Missouri, which stemmed from a previous series, Typologies of Alleyways: St. Louis, Missouri. There is a hint of Eugene Atget’s deadpan documentation of Paris fused with Dihn Q Le’s mnemonic play with sense perception in this series. While photographing deep fields of space in the initial work, she began to examine the flatness of the photographic paper that conflicted with the negative recesses of the alleyways that extended to horizon lines and vanishing points. In the completed series she physically manipulates the photographic paper by cutting into the larger prints and reforming the image to disturb a stable sense of place in the photograph.

This is an alchemical process that atavistically recalls Fox Talbot’s early experimentation with flimsy paper negatives and the more contemporary example of Vik Muniz’s crowd-pleasing paint/photo grid hybrids. The ‘image’ itself is broken when ripped out of an original context, but by reweaving the prints, a sensation of a fragmented point of view is created that subverts the ‘a priori’ fixed vantage point that defines photography’s history, the related concepts of linear perspective and its visual history in western art. The act of weaving becomes a small but significant rebellion against mechanical reproduction. The perceived image itself becomes a flattened, distorted representation depicting a space that we could not experience in the real world whilst the actual surface melts into a subtle low relief, almost a frieze, as it gains the flexible texture of a woven textile design. The interaction of the viewer with the picture varies considerably, sometimes this depends on how well versed the individual is, in photographic conventions established by masters like Atget and by the attendant, handmade disruption that is introduced.

While some images are more prosaic or familiar than others, they all invite closer examination to determine where the photograph was actually taken or if any ‘POV’ can be determined at all. Literal or visual hints about location are present but they slip and slide unsteadily generating a roving focus as the eye darts around to find a comforting focal point. These are images that also violate notions of photographs as infinitely reproducible objects: they all have a distinct existence as ‘one offs’ laboriously or if you prefer lovingly, worked on to completion. The evolution of the digital age of photography, where even location of the snap shot is recorded down to the last centimeter via satellite location, leads one to question the technological, and conceptual and perhaps even the ethical limitations of the camera and its place in the world.

Tags: Journal