Interview with Doug Ashford by Meaghan Kent 6.19.13

Meaghan Kent: There is so much that I would love to talk to you about. You had sent me these two different texts that I thought were a really nice parallel; there is the text from Interiors (“Sometimes we say Dreams When We Want to Say Hopes, or Wishes, or Aspirations” with Angelo Bellfatto) that was performed at the New Museum and the text on Group Material (“Group Material: Abstraction as the Onset of the Real”). Between reading those two, I found an interesting balance in your own work in terms of abstraction and with your work with Group Material.

The “Dead in August (DiA)” project is meant to celebrate a particular time in the city when it closes down. We focus on utilizing the city and taking advantage of these empty spaces and working with New York based artists. The panel and the Journal are ways of looking at everyone’s work through a filter of living in New York City and I know that you have lived in New York for over thirty years now.

Doug Ashford: August is one of my favorite times living in New York. You can walk right into a movie or a museum.

MK: It’s true. And with my background in galleries, everyone closes up shop and leaves and I had to question: why? When people are still around and there is all this great empty space.

So I’d like to start with a little bit of your background. You’re originally from Ithaca, so what brought you to New York City first? What were those reasons? And I’m curious if the reasons that brought you here originally are still relevant now and keep you here?

DA: Well, it was the ‘70s, and that was such a long time ago. I was really just a child, being 17, so my motivations were many and unspecific, really: art, school, clubs, people. I was coming to New York a lot in high school and I would stay at the Chelsea Hotel and at the YMCA on 23rd Street, which was across the street and the cheapest place to stay in the mid-70s. I would hitchhike down here with my friend Richard Limber and our sense was that anyone that wanted to be an artist wanted to come here. I wanted to meet more people like me. At that time, folks where I came from thought I was crazy and it was truly a different city then – so they weren’t completely wrong; coming to New York certainly wasn’t the “career choice” it seems to be now.

So why did I come to New York? I wanted to be an artist and I wanted go to The Cooper Union. I knew that much. I grew up in the academic setting of Cornell, where my father was a professor, so I had been immersed in a system of regulating knowledge that I needed to get away from.

My mother was a psychiatric social worker and a civil rights activist, and when not exhausted by family or work, she was a painter. During the illness that led to her death twenty years later, it became apparent to me that the connection I had to being an artist may not have been only my own. But you know how parenting is, right? The plans we have for our children are never completely conscious. So why did I come to New York? I came to New York because of my mother. That would be the right answer; I came to New York because of my mother! It was her nature, to be involved in social movements and aesthetic practice and that propelled me into a particular direction as a young person. When she died in 1994, Group Material was almost done with its 15 years of work. I knew she was always involved in what I did, and we spoke often of my work-but I never really knew how much the work was in her life until I went through her stuff afterwards and found she had saved everything, every announcement and article and image, everything. She was very devoted to her kids.

MK: What were her thoughts on it? Because it probably wasn’t exactly what she had imagined or thought you were making, it was a different kind of work.

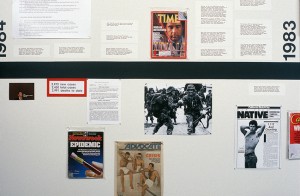

Group Material, AIDS Timeline, 1989, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacifica Film Archive, Berkeley, CA.

DA: It was in a way, she was a painter’s painter. But she was also part of a larger intellectual scene that was connected with the ‘60s art movements and happenings, as she understood them. Jim Dine was in Ithaca then, Daniel Berrigan was a pastor at Cornell chapel. My parents, as most thinkers at that time, were deeply involved in the national peace movement and civil rights struggle. It was a group of intellectuals and artists in Ithaca that were socially connected through a desperate need to create change. At least, this was my perspective as a child listening in to their parties; the hanging out, the marches and the making of artwork were seen as integrated into local friendships and love. It sounds crazy today! So anyway, my mom’s relationship to art and politics was one that made it not difficult at all for her to understand the impetus behind Group Material.

MK: So there was a sense of activism already in your system.

DA: Definitely, I inherited it without much choice. I’m a second generation of a particular shift of two people who came of intellectual age in the ‘50s and who organized their idealism around particular ideas about the changing of America. For them, this change could produce a different kind of global condition, too, through both emotional and intellectual labor. But not to overestimate their radicalism; my dad’s political science, if I look back on it now, was certainly inline with neo-liberal understanding of post-colonialism, that although perhaps more humanizing, was still based in the supposedly noble traditions of the “good European.” I was born in Morocco because he was doing his field research there and his international practice, like many at the time, was partially funded by the CIA. My dad disavowed this relationship, as did many others after the Bay of Pigs, but this history of colonialist state involvement in liberal research can’t be ignored. Such hypocrisies of the American university system were in part why I wanted to look for more autonomous intellectual associations as a young artist.

But yes, movement politics was around me the whole time I was growing up. I have baby memories of walking in Washington DC with armbands on, singing, “We Shall Not Be Moved.” A much more radical generational shift was between my parents and grandparents. My mother’s father was a member of the John Birch Society and, growing up in the South, it was quite a radical turn coming from a culture of white supremacy. When my grandfather died, we were cleaning out the house and the FBI came to look at his checkbooks. My mother was actually quite shocked because she thought the FBI only investigated progressives!

MK: So with that in mind, did you see New York as the place that would have that kind of activism?

Group Material, AIDS Timeline, 1989, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacifica Film Archive, Berkeley, CA.

DA: Yes, but for me at the time, I saw New York as a more authentic setting for both art and politics – a place where the bourgeois hypocrisies of academia might be traded in for real relationships that could bring both pure art and pure rupture with the past. Somehow I was imprinted with an idea that I would come to New York, I would make work, and I would have this autonomous and independent life, separated from market and pretention. This meant to become part of an intellectual collaboration at some level, but I was not sure how or when it would happen. Doing admissions at Cooper today, I often recognize myself in an applicant: someone who is stuck in a cultural vacuum, like my upstate New York, and is longing to be part of a group of people who are as strange and as hungry for change as they can be. Maybe all young artists still feel this way.

MK: Does this still resonate with you now? Is it a reason to stay here and for new young artists to come here?

DA: I don’t want to be nostalgic about the old New York, but you know it’s not the same. The city of 1976 was full of gaps, literally full of holes that the imagination of individuals could fill. It’s a completely different context architecturally and socially now than it was. Even the two of us sitting here now, in a renovated factory building that was once partially in ruin on a waterfront that was once full of possibilities. When I moved to South Brooklyn, these avenues seemed empty, but were full of people, full of both their desperation and their fantasies. But you know, that’s not the Manhattan of the ‘70s either, with the piers and the empty buildings. And I think it is mistake for people of my generation to overly determine the possibilities for the city in a state of ruin. Those times were horrible for many residents of the city. As a public school teacher in the early ‘80s, my romantic sense of a collapsing city was quickly corrected.

Nonetheless, in the ‘70s there was more a sense of connection for the displaced creative class outside of institutional settings. You could go to Max’s Kansas City or the Mudd Club and there would be people from all kinds of backgrounds, living anywhere or almost living nowhere. With so many invested in the same music and movement, a young person could actually fall in love with an older artist. Where does that happen now? These cross-cultural and cross-generational openings have evaporated into the overheated condition of wealth and real estate investment that now makes New York run.

But my life is very different now, and what appears to me today as a seamless or economically-controlled space might actually be full of gaps for a younger imagination. For example, take our public squares, which since 9/11 have become completely surveyed. Even in such settings, my students have been inventing their own conditions. At the same time, they are going outside the city for different kinds of contexts for public re-imagination. Perhaps the larger, architecturally determined spaces are not so central anymore. Maybe the city itself doesn’t matter. So it all has to do with one’s position in terms of the degree to which power is controlling you and your energy.

MK: How does this reflect now with activism? When you came into New York there were certain circumstances happening so I’m curious about the way you look at activism now and how it has evolved or differentiated in terms of the way it was with Group Material.

DA: One condition that was seminal in the early days of the group was the popular movement against US intervention in Central and South America. From my experience, meeting artists and intellectuals who were living in exile here was a big influence. In a sense, the work we did on Artists Call and our first Timeline came from those personal relationships. But the larger activism of artists and intellectuals in NYC came also from a larger a shift in public thinking in the ‘80s, particularly around America’s imperialist involvement in El Salvador. Here, the photographs of Susan Meiselas, and her work with the journalist Raymond Bonner of The New York Times, moved a whole generation. If they were not in El Salvador doing their work, the state-sponsored massacres of civilians would probably have never been felt as a direct product of American policy and training. It’s the event or the occurrence of an image, making something visible that was–and still is–often at the heart of political empathy. Susan was often in New York at that time, and her personal representation of the things she was documenting spoke deeply to many of us in the artistic communities of this city.

Meiselas is maybe just a bit older than I, but our shared generation has been through a range of activist conditions and political challenges that are an important part of New York’s history. Group Material was involved in the activism in the AIDS movement a few years later when working with The Dia Art Foundation, and I remember seeing some of the same people at ACT UP meetings who had been part of the solidarity work with Central and South American movements years before. Maybe if you live long enough, you can see the larger personal contexts for rebellion and the consistencies between them. Even though we all live in a state of separation from controlling of the context of representing history, we do reappear in its making! This is perhaps why aesthetics and politics are so close and why political movements are often founded in artistic desires: because they exist inside humans as things that make each other. Art is a way of showing someone how far things might have to go to get better. Knowing that something is beautiful seems proximate to figuring out how to care.

Doug Ashford, The Participants in Artists’ Call Against US Intervention in Central America and the Relationships Between Them, 2004. Artists Space, NY

I think this would be an interesting New York story for someone to write: a child that lived through the civil rights movement, and then worked as a young adult in international peace movements and ACT UP, and then became a witness to Occupy as an older person. In the present we live the idea of a means without an end, of organizing yourself without a program. The work of ACT UP changed governmental, medical and drug approval protocol within the FDA and other agencies; it changed how identity is imagined and represented in the media. So many things. There was an agenda. With Occupy, you could ask a participant, “Hey, tell me what do you want,” and they could answer, “We don’t have to tell you, we are doing it.” This is very new to me and very beautiful.

MK: This raises the bigger question: what’s the point of activism? For instance, ACT UP raised a great deal of money and had some kind of change as you mentioned with FDA guidelines.

DA: I think another question is where are the artists today in calling up political agendas? In the ‘80s, it may have not been the most visible art world practice you could see, but Leo Castelli gave time and space to Artists’ Call Against US Intervention in Central America and Tom Lawson, Coosje van Bruggen and Claes Oldenburg, and many, many others helped organize it. It is amazing that the art world could respond to something like that and literally raise $240,000 and send it to the Sandinistas. Do you realize how close to impossible that would be now? “Day Without Art” inspired a whole generation of curators and educators to acknowledge social indifference to the AIDS crisis. It is especially discouraging when we see how the gigantic resources that are in the art world of today are recycled only into bigger hedge funds. One Jeff Koons could save The Cooper Union but instead, the social projects of the 20th century are collapsing around us. It’s shocking.

Doug Ashford, The Participants in Artists’ Call Against US Intervention in Central America and the Relationships Between Them, 2004. Artists Space, NY

MK: The High Line would be a good contemporary example of what successful activism might look like today. It was initially a place that people were trying to save and has now become a completely different kind of sphere. It wasn’t necessarily preserved, but modified to become a more commercial venue.

DA: Ruling class giving now appears to be organized only around what they’re going to get back. It comes to us only in relation to an identifiable branding and the idea of a donation turning into an elevation of their profit. So the High Line, I don’t know, I haven’t gone yet. It’s not my idea of a city that I can find myself in. Maybe it’s just a generational thing. Maybe there was actual radical community investment in the building of this real estate mechanism, but it’s very hard to see. But perhaps it also signifies the way activism often truly works: radical social projects, once they become involved in a program of compromise, lose their sense of actually addressing the real life of people and become representative of something else.

MK: In terms of your own work and its relationship to this idea of political activism, what kind of connection do you see?

DA: I retreated.

MK: So it became a way of escaping?

Doug Ashford, Many Readers of One Event, 2012. Documenta 13, Karlsaue Park, Kassel.

DA: I’m still working it out. In the beginning I would make things on my own as a way to sort of organize myself in the face of these contradictions. But I have always made objects and reflected upon them and seen them as diagrams of what I did and thought and wrote about. In 2004, Andrea Geyer asked me to be in an exhibition at Artists Space (“When Artists Say We”) and I turned one of these diagrammatic pictures into a small installation. I felt a lot of satisfaction in the sense of being able to picture the sense of the paradox of ethical actions from afar. What our attention, our labor, produces in relationship to real politics is always in a context of such a compromise that the practical always seems to overtake the original aspiration. Where I teach, I helped organize a labor union and at the end of four years there was only a tenth of the hope that went into it—but it was still the right politics. My pictures are a way to reflect on failures like this, making the frustrations, and anxieties of social life subjects of potential emotional reflection.

MK: So the connection of historical images to actual physical objects creates a different position?

DA: The first pictures I made were purely abstract, although informed by historical subjects that were then completely removed. I liked to see the painted object as that which could exist as separated from reference, and I wanted the experience for the viewer to imagine this as somehow archival. I fantasized that the pictures could be organized in file cabinets or boxes somehow, the same way I keep the photo collections that inform them. Then the visual organizations of colors, just colors, began to act as a kind of dream that the anxieties of social practice could be seen through. From what I tried to unpack in the New Museum talk you mentioned—although the failures of political work were upsetting, they became understandable as something emotionally in flux, as a means without an end, if translated through abstractions.

Doug Ashford, Many Readers of One Event, 2012. Documenta 13, Karlsaue Park, Kassel.

But the context of documentation never seems to go away. This was the impetus behind the painting series, “Many Readers of One Event,” where photographs of actors are reenacting parents’ bodily response to the death of their children. Today there is always a photograph. It is that moment where you organize a search party and then somebody runs into the crowd and says we found your children and they’re dead and they’re in the trunk of a car right next to you. The conditions of the bodies are a kind of expression not meant for public scrutiny, but are there, nonetheless. At this point the work is not so much about social practice anymore, but trying to become invested in a collapsing connection between ethics and beauty, between feeling something and making it work for others. I’m trying to figure it out not in terms of a critical thesis or presenting any concrete history, but just trying to show something that through theatre could become a new response to facts. Not a sensible response, nothing particularly useful.

MK: And how did you use the color? Is it symbolic?

DA: No. It’s very unscientific. The pictures are made in groups with color relationship in mind. In the work that I do, color helps to deny any work acting as a definable instrument. But these pictures don’t come from any rejection of past interests. In a way, it is all the same project in the complex structure of making things over a life. Years ago when I was listening to all the conversations produced in the “Who Cares” project for Creative Time, I realized a context for a different marking of the investment in an artist’s work over time. You know, aesthetics as a program of self-improvement is not that interesting in the end.

MK: So what are you hoping that people will experience?

DA: I’m trying to not have any expectations. It’s hard, but I’m trying not to.

Sources:

Ashford, Doug, “Group Material: Abstraction as the Onset of the Real,” Performing the Curatorial Within and Beyond Art, edited by Maria Lind, Sternberg Press, 2012

Ashford, Doug and Angelo Bellfatto, “Sometimes We Say Dreams When We Want to Say Hopes, or Wishes, or Aspirations,” Interiors, edited by Johanna Burton, Lynne Cooke, and Josiah McElheny, Sternberg Press, 2012

Tags: Journal