The Florentine Nights Network by Pablo Helguera

“And you always loved only chiseled or painted women?” tittered Maria.

“No! I have loved dead women too,” replied Maximilian, as a very grave expression came over his features. —Heinrich Heine, The Florentine Nights

The spirits speak, despite the hypnotizer and the hypnotized. —Julio Torri

Those of us who worked for Isidoro Blackstein always wondered what would happen with his life’s work after his demise. We were all fairly certain that he had no close relatives. His house, which also functioned as a studio, was a strictly impersonal place, with no sentimental objects of any kind: no photographs or items with family history. The only person he had any apparent relationship with was his sister, who had passed away a few summers ago in Italy. His incessant work and worldwide travel allowed no time to be intimate with anyone. He was to all of us, by far, the most frenetic traveler we had ever seen—rarely staying put in one city for more than three days. He had traveled to more countries than a National Geographic journalist; he knew every airport in the world. His bathroom was full with hotel soaps and airline toothpaste tubes.

It was only the three of us, who at different times alternated being his assistant—none of us could last very long due to his difficult personality, but all of us would always come back for a time, in one way or another, as we could not bring ourselves to abandon him completely. In the end, despite Blackstein’s temper and self-absorption, there was something endearing, there was something about the work that he was doing that transcended him and us, even if we quite didn’t understand it—we knew it was important to preserve.

Blanca was the only one who dared to ask him the question once, something along the lines of, “Have you given any thought to what you want to happen with your research after you are gone?” to which he replied, “it’s for you guys,” in the most natural way, as if all along it had been clear that Blanca, Trevor and I were his adopted family.

And so it happened. One fatal day, I received a call from his cell phone. Blackstein had passed away on a plane going to Tokyo.

Before we knew it, we had to deal with his enormous archive. The three of us knew that it would be our mission to finally make sense of it, after so many years of working on only bits and pieces of research. His Lower East Side studio and apartment was only a portion of the problem. More daunting was a home he had in the country, to which none of us had ever been invited. We knew it only as the place where we were always asked to send large shipments of documents.

He wanted everybody to keep in step with him. I thought how difficult it was to do so, especially as we went through the dense woods. It had rained the night before and there was mud everywhere. We walked though quicksand areas. I was having a hard time with the incessant attacks of mosquitoes and the humid heat of mid-August that made the air almost unbreathable in that part of the Adirondacks. I was so impressed with Blackstein’s former agility and physical condition that once allowed him to traverse this area to get to his house.

The house was truly hidden. The property had belonged to the university for over a hundred years, a donation by an alumnus. At some point in the 1920s, the geography department made plans to create a summer institute. Construction started in the 1930s but soon stalled, and the university abandoned the project. In the summer of 1961, the year Blackstein started teaching, he and Professor Erick Thomanson assessed the condition of the building for the department. At the time this truly was an abandoned part of the world. It still is, I suppose, although highways have been built, and small towns have since emerged. As no one in the university saw any value in this building, not even the value in selling it, Blackstein claimed it once again as a location for his department’s summer institute—a project that would never in fact come to fruition. At first there was a good deal of objection to his proposal, but over the years everyone simply forgot this building was there. “It’s sort of a nostalgia thing,” Blackstein would say, whenever he was asked why was he heading there. It had always been my impression that Blackstein was seldom there. Whenever he was absent, I imagined him in Kamchatka or the Himalayas, not in this large and inhospitable building. But as we entered the space, we knew it contained a key to his life.

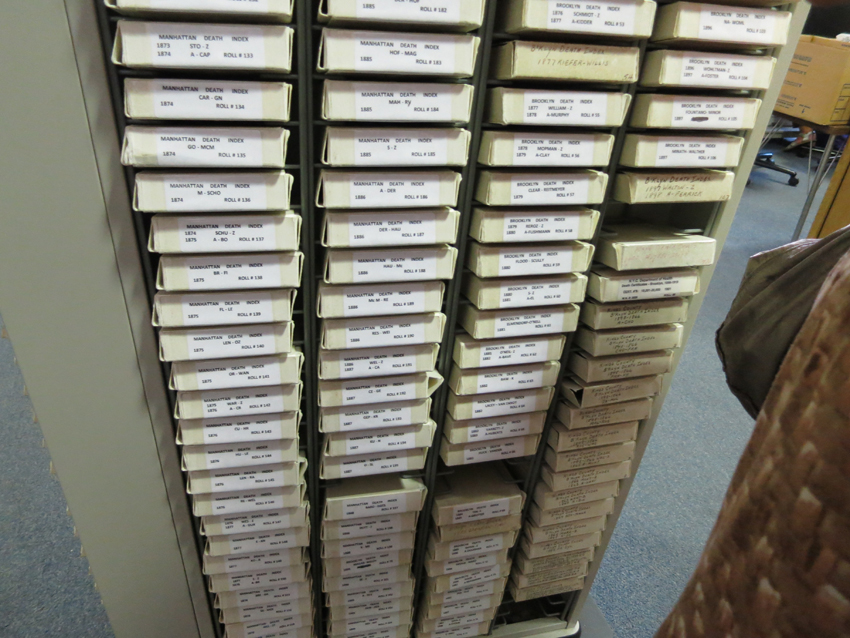

When we first entered, we all became very quiet. Nothing could have prepared us to see the monumental display of photographs that was there. After two years of cataloguing, even as of last week, we knew that we had yet to reach even a quarter of all the material. Yet, arriving there, we had suddenly accounted for three million prints. The space was organized like a postal office, with piles of prints arranged by what appeared to be zip codes. Blackstein had taken copious notes: several hundred thousand pieces of scribbled paper lay inside cabinets and binders, some of them so yellowed they were clearly from many decades before.

It would be unfair to say that this project was a hopeless mess, but we also knew that the moment we informed the university that this material was here, there would be a quick movement to retire it, and possibly even to discard it. We knew of the general lack of interest in engaging with Blackstein’s ideas held amongst his university colleagues, who always saw him as an arrogant and self-absorbed character. They were right, but we also believed that Blackstein’s demeanor had less to do with certain misogyny, but rather with a definite and complete indifference to humans.

He had written about this subject many times. Once when asked why he had become a geologist, he had said that he wanted to detach from humanity as much as possible, not because of hatred toward humans, but because “human presence always makes understanding impossible.” He clearly suffered by being human himself, and was always making an effort to erase or at least substantially minimize the fact that the observer of a phenomenon alters it by the mere act of their observation. I will now make what will likely be a poor attempt at representing Blackstein’s ideas and how they manifested in his life’s work.

Blackstein spent the last fifty years of his research focusing on the subject of conversations without living beings. To Blackstein, conversation had a different meaning than it has for someone like you or me. To him, consciousness was not merely a human attribute and, perhaps also surprisingly, he did not see it as a spiritual one either. He spent most of his life trying to prove first that spaces have genealogies and interests, elective affinities and weaknesses, and that these attributes made them attractive to other, parallel places. He went out of the way to alert the reader (who he thought of as the reader was always perplexing to me—was he writing for us, his assistants?) that he did not believe in extra-sensorial forces. Rather, he believed that geographical locations had “qualias.” It is perhaps meaningful to add here that Blackstein had studied under Clarence Irving Lewis, who in his book Mind and the World Order had first articulated the notion that:

“There are recognizable qualitative characters of the given, which may be repeated in different experiences, and are thus a sort of universals; I call these “qualia.” But although such qualia are universals, in the sense of being recognized from one to another experience, they must be distinguished from the properties of objects. Confusion of these two is characteristic of many historical conceptions, as well as of current essence-theories. The quale is directly intuited, given, and is not the subject of any possible error because it is purely subjective.”

Blackstein was heavily influenced by Lewis’s idea, though he rebelled against the notion that qualia would be necessarily an attribute that could easily be detached from objects and limited to humans. According to Blackstein, “just because we as humans possess consciousness that allows us to make sense of the world and become aware of our own awareness, this doesn’t allow us to conclude that things, or places don’t have a version of awareness of their own.” “This is not to say,” Blackstein added in his notes, “that places have feelings or a thought process, but they inhabit their identity in the same way in which we inhabit a state of mind, for which we don’t need to have a reflection about when we are inhabiting it.”

This line of argument eventually led Blackstein to what would become his half-century quest to identify forms of qualias for various places, forming taxonomies and traveling to distant lands to recognize familiar relations between one place and another. He believed that in the formation of the planet, most of these locations had been together at one point, and as the earth’s pangea had separated, these places had also detached from each other, eventually spreading throughout the world. Blackstein had created a taxonomy for those places:

Network 1- places of abandonment

Network 2- places before violence

Network 3- sites of vicarious living

Network 4- storage spaces

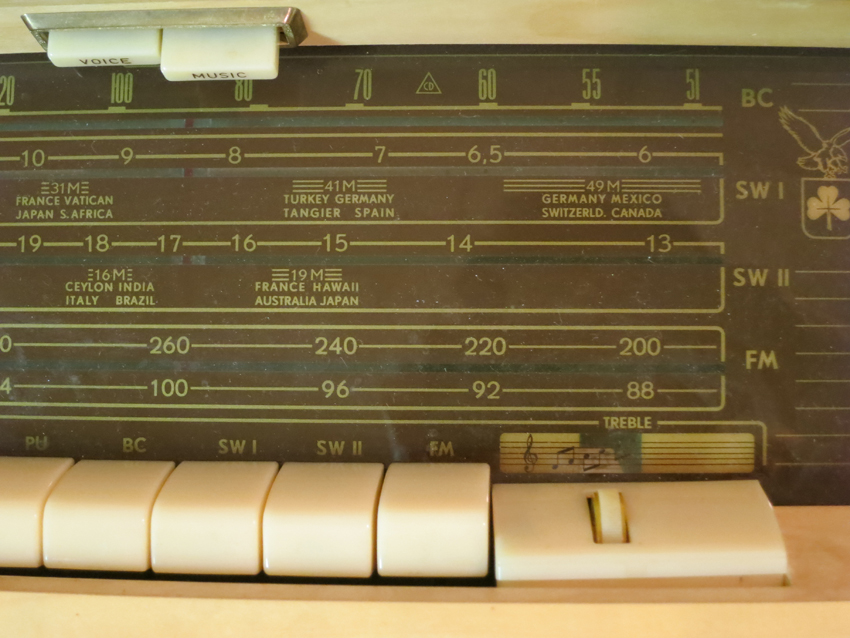

Network 5- places that pretend to be other, distant places

Network 6- places that contain objects from another time

Network 7- haunted places

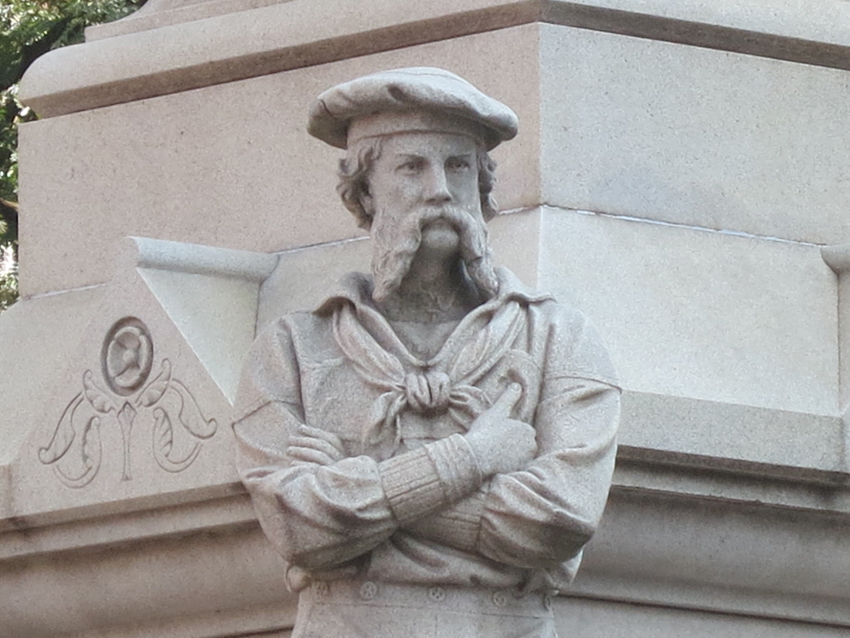

Network 8- historically recreated places

Network 9- the space between sky and earth

Network 10- places in waiting

Looking at Blackstein’s notes, it is very clear that this particular breakthrough in his research came at a very early point; he must have been in his early twenties when he made these initial observations. What came over the ensuing five decades is clearly a development of the natural consequences of these ideas. What we always thought was a geological study of subsoil at the locations he was traveling to and the documentation he gathered of those places, was in fact a continuous and methodical series of journeys to create a map of geographic qualias, trying to find the ultimate typologies for different man-made and non-man-made locations (to him, the intervention of the human hand was irrelevant; he believed that any intervention was always meant to result inevitably in the furthering of the already existing identity of that place).

As it happens to most of us, Blackstein’s efforts were cut short by his own demise. His final conclusion, which he clearly thought he was close to writing and disseminating, never saw the light of day. For those of us who knew him, we could always recognize that while he held himself to the most critical standards, he never felt lost. Instead, he was someone who had a puzzle in front of him and knew what needed to happen—he only labored to find the right places for the pieces. Thinking in retrospect, only once do I recall sensing that Blackstein betrayed doubts of his work. It was an exchange that stayed in my mind and which at the time did not make much sense. As we were working on organizing the documentation of one of many thousand sites, he seemed to be deep in thought. He asked me:

“If you were a place instead of a person, what kind of place would you be?”

“Do I get to choose?” I asked, thinking it was a game.

“No. I am asking what sort of place is the equivalent of what you are right now, how you feel right now.”

I remember I couldn’t quite give him an answer. But I never forgot his question. And today, after thinking about him—his constant mobility and his inability to stay in one single place for more than a day or so, I finally understand that to Blackstein the real challenge had never been to create a unified theory of qualias and places, or a geographic theory of consciousness. It was to find the place equivalent to him. His summer home, with the millions of photographs, was perhaps his way to search for a location, or rather, to convince himself that he could find himself comfortable in one place and merge an identity with it, regardless how inhospitable it became. It was some perverse way, perhaps, to prove that he and his theories were right. Perhaps he realized that he was in search of an ultimate location that is permanently changing, like Heraclitus’s river, always gone or distant by the time he arrived to grasp it, leaving him to forever pursue his own shadow.

Tags: Journal