02 06

02 06

DOWNLOAD PDF: site95_Journal_02_06.e

Editor in Chief Meaghan Kent, Contributing Editor Janet Kim, Copy Editor Beth Maycumber, Copy Editor Jennifer Soosaar, Copy Writers Kati Henderson, Tyler Gorky, and Pooja Kakar

Curated by Meaghan Kent

Featuring: Sarah Charlesworth, Doug Ashford, Noah Becker, Sue de Beer, and Ryan McNamara

Journal designed by SITE, Logo designed by Fulano

Interviews by Meaghan Kent. In conjunction with the “New York Practice” panel discussion at Independent Curators International (ICI) with Noah Becker, Sue de Beer, and Ryan McNamara on August 1, 2013. Special thanks to Kate Fowle, Renaud Proch, Maria del Carmen Carrión, and Misa Jeffereis at Independent Curators International (ICI), Veronica Levitt at Marianne Boesky Gallery, Lauren Allegrezza and Jennifer Brennan at Elizabeth Dee Gallery.

Interview with Sarah Charlesworth by Meaghan Kent 12.8.98

In the series of interviews presented in this Journal, I asked each of the artists what their motivating factors were that brought them to New York and if those reasons still resonate now. A significant moment for me was an interview I conducted with Sarah Charlesworth after her solo exhibition at SITE Santa Fe in 1998. I was completing my undergraduate thesis on postmodern feminism. I interviewed her over the phone; Charlesworth in her studio in New York while I was in Santa Fe. I could hear the sound of New York traffic in the background and I couldn’t help but find it foreign and extraordinarily exciting.

As I prepared for “New York Practice” over the last several months, Sarah Charlesworth and our interview has been on my mind. Included here is an excerpt from that interview.

Sarah Charlesworth: I was doing my first shows in New York in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s at the same time as Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, Laurie Simmons, and Barbara Kruger. We all emerged as young artists at the same time. I think we have all been influenced by similar things.

Using photography as a medium and appropriated imagery has a lot do with issues in the generation just slightly older than us. I was particularly influenced by Conceptual artists in New York but also LA, such as John Baldessari and Ed Ruscha. Also, Pop art was a big movement when we were in college. But the larger cultural issues as self-expression was a big looming subject that hadn’t really been addressed.

Meaghan Kent: Postmodernism was coined in New York in the ‘60s and spread throughout the ‘70s. When did you first hear the term?

SC: There was book in the late ‘60s—early ‘70s that I remember as the first time I learned of it; it was about architecture, postmodern architecture. It had very much to do with the use of quotation and the idea of mixed metaphors; it was drawing from other sources rather than using a traditional style, more of an eclectic style. Eclecticism in itself is not interesting; it was the underlining fact that we live in a culture which draws from a different number of sources. There isn’t one specific American source or culture. There isn’t one that defines who we are. It is a blend of influences and histories that are, in fact, present in contemporary experience.

I think with architecture these are part of the traditions that we inherit, so different idioms were borrowed rather than one pure style. The idea of mixed quotational references was very much part of what postmodernism meant. I remember initially rejecting the idea because it initially meant everything and anything that came along.

The first time I heard it used to refer to my work was in a panel in 1983. Douglas Crimp was the moderator of the panel and he taught postmodernism and photography. I hated the word and I tried to reject the word. On the other hand, it seemed like modernism had run its course. There was something else that was emerging and that something else grew from a new kind of cultural experience that was very different from the modernist experience.

MK: In your work, what were some of the distinguishing factors?

SC: I think it has a lot to do with technologies. The way culture has experienced everything from jet travel to TV. Because there is so much sharing of imagery and languages. The moment where we can buy food from every culture. New York, for example, with its different cuisines. These cultures influence each other in so many different ways.

In terms of postmodernism, it seemed to jump off from the point where modernism didn’t have any more questions to ask but there were lots of broader issues that art could address. There was the Feminist Movement. Throughout history, right up to the ‘50s and early ‘60s, women were definitely considered second class citizens in every possible way, in spoken, written and visual language. It took a generation of artists, writers, anthropologists to articulate that this way of viewing ourselves doesn’t empower women. We refer to artists, presidents, and lawyers as he and man. We’ve always created imagery that advanced male culture but doesn’t advance female culture. These feminist and racial issues simultaneously took place with the emergence of postmodern culture and had very much to do with getting outside the “art for arts sake” model.

MK: And that’s why you created, or attempted to create a new language?

SC: Very much so, yes. The women of my generation didn’t want to be considered a woman artist but an artist and they wanted to be able to participate in the same galleries, museum and magazines.

It took a group of women twenty-five years ago to push the idea that an artist or a doctor or a lawyer could be a she too. So we’ll make that space in that language for that possibility by saying he or she. It makes a huge difference. It makes possibilities for people to be able to invent themselves.

Sarah Charlesworth 1947—2013

Interview with Doug Ashford by Meaghan Kent 6.19.13

Meaghan Kent: There is so much that I would love to talk to you about. You had sent me these two different texts that I thought were a really nice parallel; there is the text from Interiors (“Sometimes we say Dreams When We Want to Say Hopes, or Wishes, or Aspirations” with Angelo Bellfatto) that was performed at the New Museum and the text on Group Material (“Group Material: Abstraction as the Onset of the Real”). Between reading those two, I found an interesting balance in your own work in terms of abstraction and with your work with Group Material.

The “Dead in August (DiA)” project is meant to celebrate a particular time in the city when it closes down. We focus on utilizing the city and taking advantage of these empty spaces and working with New York based artists. The panel and the Journal are ways of looking at everyone’s work through a filter of living in New York City and I know that you have lived in New York for over thirty years now.

Doug Ashford: August is one of my favorite times living in New York. You can walk right into a movie or a museum.

MK: It’s true. And with my background in galleries, everyone closes up shop and leaves and I had to question: why? When people are still around and there is all this great empty space.

So I’d like to start with a little bit of your background. You’re originally from Ithaca, so what brought you to New York City first? What were those reasons? And I’m curious if the reasons that brought you here originally are still relevant now and keep you here?

DA: Well, it was the ‘70s, and that was such a long time ago. I was really just a child, being 17, so my motivations were many and unspecific, really: art, school, clubs, people. I was coming to New York a lot in high school and I would stay at the Chelsea Hotel and at the YMCA on 23rd Street, which was across the street and the cheapest place to stay in the mid-70s. I would hitchhike down here with my friend Richard Limber and our sense was that anyone that wanted to be an artist wanted to come here. I wanted to meet more people like me. At that time, folks where I came from thought I was crazy and it was truly a different city then – so they weren’t completely wrong; coming to New York certainly wasn’t the “career choice” it seems to be now.

So why did I come to New York? I wanted to be an artist and I wanted go to The Cooper Union. I knew that much. I grew up in the academic setting of Cornell, where my father was a professor, so I had been immersed in a system of regulating knowledge that I needed to get away from.

My mother was a psychiatric social worker and a civil rights activist, and when not exhausted by family or work, she was a painter. During the illness that led to her death twenty years later, it became apparent to me that the connection I had to being an artist may not have been only my own. But you know how parenting is, right? The plans we have for our children are never completely conscious. So why did I come to New York? I came to New York because of my mother. That would be the right answer; I came to New York because of my mother! It was her nature, to be involved in social movements and aesthetic practice and that propelled me into a particular direction as a young person. When she died in 1994, Group Material was almost done with its 15 years of work. I knew she was always involved in what I did, and we spoke often of my work-but I never really knew how much the work was in her life until I went through her stuff afterwards and found she had saved everything, every announcement and article and image, everything. She was very devoted to her kids.

MK: What were her thoughts on it? Because it probably wasn’t exactly what she had imagined or thought you were making, it was a different kind of work.

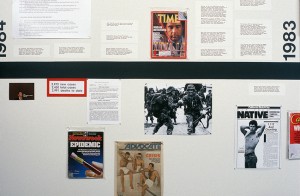

Group Material, AIDS Timeline, 1989, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacifica Film Archive, Berkeley, CA.

DA: It was in a way, she was a painter’s painter. But she was also part of a larger intellectual scene that was connected with the ‘60s art movements and happenings, as she understood them. Jim Dine was in Ithaca then, Daniel Berrigan was a pastor at Cornell chapel. My parents, as most thinkers at that time, were deeply involved in the national peace movement and civil rights struggle. It was a group of intellectuals and artists in Ithaca that were socially connected through a desperate need to create change. At least, this was my perspective as a child listening in to their parties; the hanging out, the marches and the making of artwork were seen as integrated into local friendships and love. It sounds crazy today! So anyway, my mom’s relationship to art and politics was one that made it not difficult at all for her to understand the impetus behind Group Material.

MK: So there was a sense of activism already in your system.

DA: Definitely, I inherited it without much choice. I’m a second generation of a particular shift of two people who came of intellectual age in the ‘50s and who organized their idealism around particular ideas about the changing of America. For them, this change could produce a different kind of global condition, too, through both emotional and intellectual labor. But not to overestimate their radicalism; my dad’s political science, if I look back on it now, was certainly inline with neo-liberal understanding of post-colonialism, that although perhaps more humanizing, was still based in the supposedly noble traditions of the “good European.” I was born in Morocco because he was doing his field research there and his international practice, like many at the time, was partially funded by the CIA. My dad disavowed this relationship, as did many others after the Bay of Pigs, but this history of colonialist state involvement in liberal research can’t be ignored. Such hypocrisies of the American university system were in part why I wanted to look for more autonomous intellectual associations as a young artist.

But yes, movement politics was around me the whole time I was growing up. I have baby memories of walking in Washington DC with armbands on, singing, “We Shall Not Be Moved.” A much more radical generational shift was between my parents and grandparents. My mother’s father was a member of the John Birch Society and, growing up in the South, it was quite a radical turn coming from a culture of white supremacy. When my grandfather died, we were cleaning out the house and the FBI came to look at his checkbooks. My mother was actually quite shocked because she thought the FBI only investigated progressives!

MK: So with that in mind, did you see New York as the place that would have that kind of activism?

Group Material, AIDS Timeline, 1989, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacifica Film Archive, Berkeley, CA.

DA: Yes, but for me at the time, I saw New York as a more authentic setting for both art and politics – a place where the bourgeois hypocrisies of academia might be traded in for real relationships that could bring both pure art and pure rupture with the past. Somehow I was imprinted with an idea that I would come to New York, I would make work, and I would have this autonomous and independent life, separated from market and pretention. This meant to become part of an intellectual collaboration at some level, but I was not sure how or when it would happen. Doing admissions at Cooper today, I often recognize myself in an applicant: someone who is stuck in a cultural vacuum, like my upstate New York, and is longing to be part of a group of people who are as strange and as hungry for change as they can be. Maybe all young artists still feel this way.

MK: Does this still resonate with you now? Is it a reason to stay here and for new young artists to come here?

DA: I don’t want to be nostalgic about the old New York, but you know it’s not the same. The city of 1976 was full of gaps, literally full of holes that the imagination of individuals could fill. It’s a completely different context architecturally and socially now than it was. Even the two of us sitting here now, in a renovated factory building that was once partially in ruin on a waterfront that was once full of possibilities. When I moved to South Brooklyn, these avenues seemed empty, but were full of people, full of both their desperation and their fantasies. But you know, that’s not the Manhattan of the ‘70s either, with the piers and the empty buildings. And I think it is mistake for people of my generation to overly determine the possibilities for the city in a state of ruin. Those times were horrible for many residents of the city. As a public school teacher in the early ‘80s, my romantic sense of a collapsing city was quickly corrected.

Nonetheless, in the ‘70s there was more a sense of connection for the displaced creative class outside of institutional settings. You could go to Max’s Kansas City or the Mudd Club and there would be people from all kinds of backgrounds, living anywhere or almost living nowhere. With so many invested in the same music and movement, a young person could actually fall in love with an older artist. Where does that happen now? These cross-cultural and cross-generational openings have evaporated into the overheated condition of wealth and real estate investment that now makes New York run.

But my life is very different now, and what appears to me today as a seamless or economically-controlled space might actually be full of gaps for a younger imagination. For example, take our public squares, which since 9/11 have become completely surveyed. Even in such settings, my students have been inventing their own conditions. At the same time, they are going outside the city for different kinds of contexts for public re-imagination. Perhaps the larger, architecturally determined spaces are not so central anymore. Maybe the city itself doesn’t matter. So it all has to do with one’s position in terms of the degree to which power is controlling you and your energy.

MK: How does this reflect now with activism? When you came into New York there were certain circumstances happening so I’m curious about the way you look at activism now and how it has evolved or differentiated in terms of the way it was with Group Material.

DA: One condition that was seminal in the early days of the group was the popular movement against US intervention in Central and South America. From my experience, meeting artists and intellectuals who were living in exile here was a big influence. In a sense, the work we did on Artists Call and our first Timeline came from those personal relationships. But the larger activism of artists and intellectuals in NYC came also from a larger a shift in public thinking in the ‘80s, particularly around America’s imperialist involvement in El Salvador. Here, the photographs of Susan Meiselas, and her work with the journalist Raymond Bonner of The New York Times, moved a whole generation. If they were not in El Salvador doing their work, the state-sponsored massacres of civilians would probably have never been felt as a direct product of American policy and training. It’s the event or the occurrence of an image, making something visible that was–and still is–often at the heart of political empathy. Susan was often in New York at that time, and her personal representation of the things she was documenting spoke deeply to many of us in the artistic communities of this city.

Meiselas is maybe just a bit older than I, but our shared generation has been through a range of activist conditions and political challenges that are an important part of New York’s history. Group Material was involved in the activism in the AIDS movement a few years later when working with The Dia Art Foundation, and I remember seeing some of the same people at ACT UP meetings who had been part of the solidarity work with Central and South American movements years before. Maybe if you live long enough, you can see the larger personal contexts for rebellion and the consistencies between them. Even though we all live in a state of separation from controlling of the context of representing history, we do reappear in its making! This is perhaps why aesthetics and politics are so close and why political movements are often founded in artistic desires: because they exist inside humans as things that make each other. Art is a way of showing someone how far things might have to go to get better. Knowing that something is beautiful seems proximate to figuring out how to care.

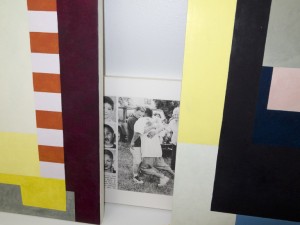

Doug Ashford, The Participants in Artists’ Call Against US Intervention in Central America and the Relationships Between Them, 2004. Artists Space, NY

I think this would be an interesting New York story for someone to write: a child that lived through the civil rights movement, and then worked as a young adult in international peace movements and ACT UP, and then became a witness to Occupy as an older person. In the present we live the idea of a means without an end, of organizing yourself without a program. The work of ACT UP changed governmental, medical and drug approval protocol within the FDA and other agencies; it changed how identity is imagined and represented in the media. So many things. There was an agenda. With Occupy, you could ask a participant, “Hey, tell me what do you want,” and they could answer, “We don’t have to tell you, we are doing it.” This is very new to me and very beautiful.

MK: This raises the bigger question: what’s the point of activism? For instance, ACT UP raised a great deal of money and had some kind of change as you mentioned with FDA guidelines.

DA: I think another question is where are the artists today in calling up political agendas? In the ‘80s, it may have not been the most visible art world practice you could see, but Leo Castelli gave time and space to Artists’ Call Against US Intervention in Central America and Tom Lawson, Coosje van Bruggen and Claes Oldenburg, and many, many others helped organize it. It is amazing that the art world could respond to something like that and literally raise $240,000 and send it to the Sandinistas. Do you realize how close to impossible that would be now? “Day Without Art” inspired a whole generation of curators and educators to acknowledge social indifference to the AIDS crisis. It is especially discouraging when we see how the gigantic resources that are in the art world of today are recycled only into bigger hedge funds. One Jeff Koons could save The Cooper Union but instead, the social projects of the 20th century are collapsing around us. It’s shocking.

Doug Ashford, The Participants in Artists’ Call Against US Intervention in Central America and the Relationships Between Them, 2004. Artists Space, NY

MK: The High Line would be a good contemporary example of what successful activism might look like today. It was initially a place that people were trying to save and has now become a completely different kind of sphere. It wasn’t necessarily preserved, but modified to become a more commercial venue.

DA: Ruling class giving now appears to be organized only around what they’re going to get back. It comes to us only in relation to an identifiable branding and the idea of a donation turning into an elevation of their profit. So the High Line, I don’t know, I haven’t gone yet. It’s not my idea of a city that I can find myself in. Maybe it’s just a generational thing. Maybe there was actual radical community investment in the building of this real estate mechanism, but it’s very hard to see. But perhaps it also signifies the way activism often truly works: radical social projects, once they become involved in a program of compromise, lose their sense of actually addressing the real life of people and become representative of something else.

MK: In terms of your own work and its relationship to this idea of political activism, what kind of connection do you see?

DA: I retreated.

MK: So it became a way of escaping?

Doug Ashford, Many Readers of One Event, 2012. Documenta 13, Karlsaue Park, Kassel.

DA: I’m still working it out. In the beginning I would make things on my own as a way to sort of organize myself in the face of these contradictions. But I have always made objects and reflected upon them and seen them as diagrams of what I did and thought and wrote about. In 2004, Andrea Geyer asked me to be in an exhibition at Artists Space (“When Artists Say We”) and I turned one of these diagrammatic pictures into a small installation. I felt a lot of satisfaction in the sense of being able to picture the sense of the paradox of ethical actions from afar. What our attention, our labor, produces in relationship to real politics is always in a context of such a compromise that the practical always seems to overtake the original aspiration. Where I teach, I helped organize a labor union and at the end of four years there was only a tenth of the hope that went into it—but it was still the right politics. My pictures are a way to reflect on failures like this, making the frustrations, and anxieties of social life subjects of potential emotional reflection.

MK: So the connection of historical images to actual physical objects creates a different position?

DA: The first pictures I made were purely abstract, although informed by historical subjects that were then completely removed. I liked to see the painted object as that which could exist as separated from reference, and I wanted the experience for the viewer to imagine this as somehow archival. I fantasized that the pictures could be organized in file cabinets or boxes somehow, the same way I keep the photo collections that inform them. Then the visual organizations of colors, just colors, began to act as a kind of dream that the anxieties of social practice could be seen through. From what I tried to unpack in the New Museum talk you mentioned—although the failures of political work were upsetting, they became understandable as something emotionally in flux, as a means without an end, if translated through abstractions.

Doug Ashford, Many Readers of One Event, 2012. Documenta 13, Karlsaue Park, Kassel.

But the context of documentation never seems to go away. This was the impetus behind the painting series, “Many Readers of One Event,” where photographs of actors are reenacting parents’ bodily response to the death of their children. Today there is always a photograph. It is that moment where you organize a search party and then somebody runs into the crowd and says we found your children and they’re dead and they’re in the trunk of a car right next to you. The conditions of the bodies are a kind of expression not meant for public scrutiny, but are there, nonetheless. At this point the work is not so much about social practice anymore, but trying to become invested in a collapsing connection between ethics and beauty, between feeling something and making it work for others. I’m trying to figure it out not in terms of a critical thesis or presenting any concrete history, but just trying to show something that through theatre could become a new response to facts. Not a sensible response, nothing particularly useful.

MK: And how did you use the color? Is it symbolic?

DA: No. It’s very unscientific. The pictures are made in groups with color relationship in mind. In the work that I do, color helps to deny any work acting as a definable instrument. But these pictures don’t come from any rejection of past interests. In a way, it is all the same project in the complex structure of making things over a life. Years ago when I was listening to all the conversations produced in the “Who Cares” project for Creative Time, I realized a context for a different marking of the investment in an artist’s work over time. You know, aesthetics as a program of self-improvement is not that interesting in the end.

MK: So what are you hoping that people will experience?

DA: I’m trying to not have any expectations. It’s hard, but I’m trying not to.

Sources:

Ashford, Doug, “Group Material: Abstraction as the Onset of the Real,” Performing the Curatorial Within and Beyond Art, edited by Maria Lind, Sternberg Press, 2012

Ashford, Doug and Angelo Bellfatto, “Sometimes We Say Dreams When We Want to Say Hopes, or Wishes, or Aspirations,” Interiors, edited by Johanna Burton, Lynne Cooke, and Josiah McElheny, Sternberg Press, 2012

Interview with Noah Becker by Meaghan Kent 7.3.13

Meaghan Kent: Shall we start by looking at your work?

Noah Becker: Do you want to see it?

MK: I would love to. I haven’t seen them in person before. Although, I might have, because you did the show at Launch F18 in TriBeCa with Sam (Trioli) and Tim (Donovan), right?

NB: Yes.

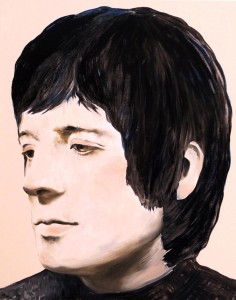

MK: These are all self-portraits in this exhibition “Stranger” at Flowers Gallery, London?

NB: Yes. This is a self-portrait that I was working on. It’s part of a series that I’m doing where I’m inserting myself into the canon, as opposed to waiting for people to put me in. Brushstrokes are all outlined with a line on each side and the actual curve of them is really measured. When I’m doing background, I try to keep it in a different state of mind than the figure so this is shifting into more of a classical representation.

MK: So it’s not an exact replication.

NB: Basically, I’m taking a picture of myself and I’m photo-shopping it over the painting. I’m trying to get as close as I can to the feeling of the background, but where there’s drips and that kind of stuff, they’re actually rendered to look like drips, as opposed to actually being drips. So it’s kind of like a way of integrating things that people really recognize. In a sense it is like Warhol, a Campbell soup can or something, he might take a Campbell soup can because he knows that it is recognizable. It’s like a household name. I’m trying to figure out ways of integrating images of modern art that people already directly identify with and somehow integrate it with my work.

MK: I just learned the expression, “selfie.” It has the feel of a “selfie.”

NB: That’s kind of what it is, a photo-bomb or a “selfie.” All of a sudden, I’m just kind of there. It is funny in a certain way, but I don’t really like to use the term “poking fun” because I think that’s a little too much of like a jokey sort of thing.

MK: This ties in a way with the focus on living in New York and the way that you are able to kind of get this rare opportunity here. You can stand in front of a Basquiat pretty easily; even in a gallery setting, you can get pretty close. It’s a unique accessibility that you have here.

NB: On another level, I’m a jazz musician as well as a painter. I play the saxophone. I listen to bebop or I listen to John Coltrane. New York is certainly a melting pot but even when you look at Warhol, it is on a certain level of reality, although it’s famous internationally, local art.

I was born in Cleveland but I grew up in Canada so I’m a duel citizen of Canada and the U.S. When you have something that’s like local art or the local music scene in a small town in Canada, that’s very specific to there. When you get here you don’t think about it as being local art and music. Even though it’s international art as well, it’s local art, and not everything that’s shown in New York is famous in New York as local art.

MK: I definitely feel like there is kind of an art world critique that permeates most of your work.

NB: Yes, it’s getting that way. I also started to collage in elements and work comes out through the editing process. The thing with neon signs, this part of the series of putting the sports bar atmosphere into Italian Renaissance painting- It’s a really ridiculous idea but then as it develops, it gets less ridiculous.

MK: If you think of a historical painter who was doing these day-to-day portraits in casual environments and how that would change if they made work now.

NB: I think that the dark areas in a lot of these old master paintings wouldn’t be dark. If they were doing the exact same work for the first time now, they would be putting things like neon signs and whatever inhabits electrically-lit areas, as opposed to areas that are lit up or not lit up at all.

MK: True. We are not necessarily in darkly lit kinds of saloons anymore. It’s an interesting way of making a painting feel current. The photo-shopping too.

NB: Also on a literary level, just on the basis of how people talk about it, or how it’s written about, or the words that come out of it and these different associations, may not have anything to do with the work. It’s kind of a twist to throw in something that may or may not have anything to do with the references.

MK: So it’s something you’re thinking of kind of randomly, but then changes as it’s coming together?

NB: It’s almost like witchcraft, like every time I do something, like making a voodoo doll, it seems to have some kind of direct implication in my life. It’s just kind of weird.

MK: It seems like a lot of trial and error through the process, but then that final outcome is pretty exact. What is it like when you’re painting another artist’s painting? Like Basquiat, for example.

NB: I try to paint at the speed at which he worked from films that I’ve seen of him painting. Things are just being put down very quickly and very directly. This is another series of British hair models.

MK: Of different celebrities?

NB: No, not celebrities, amateur hair models. I have a lot of portrait stuff a little larger and then smaller but I’m kind of starting to mix it up. Some of those I did in Canada, so also my New York time is starting to kick in in a way, and it’s difficult to work in the same way when you’re in a different place. Things are starting to get a little bit more experimental and have more elements happening in them. I’m being a little more open to Pop art and things that are happening at the time.

My art career started in Miami in 2006 and turned into me wanting to start an art magazine for reasons of almost being driven crazy by being in the art world. I was frustrated. I said to myself, “If I’m going be involved in this, I can’t just have my work sitting in some rack or gallery somewhere being neglected.” I felt like I had the quality and capability to be more of a brand, more like a major gallery or museum rather than be like, “hey, look at my paintings.” I had been an unknown artist for twenty years at that point and had become so frustrated. Also, part of it was the flaws I saw in the publishing world, the way that the art world hadn’t seen its potential online. So I started an online magazine. Prior to this there was only artnet.com and artforum.com.

And this is recent history, not 20 years. In 2006, I was in Canada and when I looked at artnet.com, I would have to click to the magazine part. By the time you’re through, you’ve clicked like four or five times to get to the magazine. artforum.com was mostly paparazzi photos. It’s not like a real art magazine at your fingertips, with real articles and major reviews. It’s not like a virtual art magazine experience. It was websites and I was a person that was interested in a magazine. I still feel like I’ve gained a lot from those places, but as far as online magazines go, I saw that there was something that was missing.

You would bounce from gallery website to gallery website to look at different artists work, and then you would see all the press releases that the gallery manager is doing, and look at all the MFA’s that are graduating who are fluent in art criticism, but then we have to hear from one of the three art critics that were in existence and how they were feeling on that particular day in five or six glossy pages in a magazine. I would read a few articles where the art critics were writing all about them, not really about the work, and I thought at least two of these pages could’ve been devoted to someone unknown, someone starving and dedicated to art and who needs coverage, a small gallery, a small curator, anything- there’s so many people.

So I kind of tapped into the Warhol model there as well, the way Warhol was dealing with superstars and I started to realize there were a lot of people who did not fit the profile of art critic or journalist who could write well and had a valuable perspective on the art world. I put the word out one day that I was going to start the biggest art magazine since artforum.com and artnet. I put out this insane email out through my hotmail account and told my friends that I had quit being an artist, that I couldn’t hack it anymore. I was done, I quit. I grew a beard and never left the house. I woke up the next day and checked my email and I had 800 emails from people stating, “I heard you’re starting a magazine; I’m an MFA from like Pennsylvania”; “I’m in LA and I write”; and on and on. All of these people wanted to write for me and I didn’t even have a magazine, I didn’t have a website. I had never been an editor. I had never done any of that.

Eventually what happened is just because of strange timing, the brand name I had spent time on really caught on and I started making changes to how the site navigated and I got a call from a curator in Belgium who used to teach at NYU, “I know you’re up in Canada, but let’s do a launch festival on the Lower East Side,” and that was in 2007, when the galleries were just getting started there. We said, ok, we’re going to launch a festival for White Hot magazine. Like how Facebook started in 2007, there’s now all these other sites that directly borrow stuff that I kind of pioneered. I borrowed stuff, too, but this kind of online art magazine format, I like to think I pioneered it.

MK: With the film, “New York is Now,” how did you decide on the participants in the film?

NB: Various reasons. For instance, I met Richard Phillips prior because I had written about him.

MK: They were people that you knew or wanted to speak to about a specific time in New York?

NB: Many of these people were also writers, it was more filmic than straight interviews. It wasn’t like “60 Minutes.” I was going to different peoples studios, walking through Chelsea, the Chelsea Hotel, Christie’s Auction House, there are street shots throughout New York.

MK: What brought you to New York originally, and do those reasons still resonate with you today?

NB: I grew up in British Columbia, even though I was born in Ohio, and I’ve always played the saxophone. A drummer, who was a really good friend of mine and has since passed away, started to come down to New York quite often and told me to get out of western Canada and play in a NY jazz band. So my initial inspiration to come to New York was to play jazz. In the ‘90s I was playing regularly in clubs in the New York area. I still do a lot of music stuff. Outside of jazz, there’s not a huge demand for a saxophone. So I started living in these jazz networks of small rooms that were like $400 a month. Jazz musicians had created a secret jazz community in Park Slope. I moved into one of those houses with some very famous jazz musicians, who I’m still in touch with and play with occasionally. I have a jazz musician identity in New York that helped me integrate into the city without directly going into the art scene. After 9/11, I went to Canada for ten years. People started getting interested in the kind of painting I was doing and I moved back to New York.

It’s a question of committing, it’s not a question of being afraid of what you can’t do or what you want to do, it’s a question of committing to the intangible. It’s like a parachute mentality where you hope that it opens.

MK: It’s interesting that you were in this collaborative of jazz musicians, which is very different than meeting people in the art world. People collaborate, but not in the same way musicians do.

NB: Small art community, small music community through the art community. I met some very famous artists. I think I might just continue to make films like the Warhol model. He made films about the people around him making art. The magazine has high level and respected contributors. I do have knowledge of what holds people’s attention and what doesn’t hold their attention. Entertaining people is harder than you might think. You either have it, or you don’t.

Interview with Sue de Beer by Meaghan Kent 7.2.13

Meaghan Kent: So how did you connect with Westbeth, to be able to get them to loan the space?

Sue de Beer: Someone at the LMCC put me in touch with Westbeth. Their basement space was severely flooded by Hurricane Sandy. This space we are standing in used to be an archive space for the Martha Graham Dance Company. The water flooded the space up to that black line. It was devastating for their archive; everything was ruined down here.

MK: The Dance Company archives?

SdB: Yes. Westbeth emptied it out and cleaned it, but they can’t put long-term storage in here for now. I believe they are sorting out what to do with the space. It was lovely that they offered it to me for the shoot. I haven’t had the space to shoot like this since “The Quickening,” which was shot in Berlin.

I also am working with a new writer, Nathaniel Axel.

MK: In work you have made before, you wrote the text? Or were they found sources?

SdB: Alissa Bennett worked with me on a number of scripts. She worked on “Hans and Grete,” “Disappear Here,” and “The Ghosts,” amongst others. She would write monologue texts for the characters in the film, and created some beautiful, memorable lines, like: “I’m going to erase myself, and you’re going to find me everywhere.” A great depiction of suicide. I have also adapted texts from Dennis Cooper (for my film “Black Sun”) and J.K. Huysmans (“the Quickening”).

I started my collaboration with Nate with a somewhat controlled/controlling working process, where I sent him text and asked him just to re-write the language. We were getting nowhere with that method and I could see he felt trapped by the process. So I asked him to write anything—to just write a text—and gave him a length for the text. And he wrote a wild short text and that became closer to the work we have now. So he would write and I would respond to it. The script so far has links with Lovecraft and to my mind, a New England inflected version of the Occult. He has a more masculine voice that I am interested in, and the piece has become more violent, with some horror.

We ran a casting call before finishing the script, and cast a male lead that was the opposite of the character we had been developing for the film. This man disappeared from the project, and I had to replace him, but his physical presence changed the script. He was a lot older than the actress and we were going to dye his hair black and make him a seedy, marginal figure.

MK: He came in and auditioned, but he’s not actually going to be in the project?

SdB: It didn’t work out with him in the end. But the thing about having him for that short amount of time is that it changed the script. It opened up gaps in the script, made it different. Darker. Now I’m casting to replace him. I meet the last person tomorrow so we should know Monday. I start shooting on Monday as well.

MK: I had read that you often work with non-actors. Are these not professional actors?

SdB: Yes. The person that messaged me just now is a musician and I’m meeting with another musician tomorrow. I like working with musicians because they are comfortable in front of the camera. They have great faces and they’re not acting which is really what I want.

MK: And there was also a drug in the script that you mentioned earlier… Tramodol? Does it have some kind of hallucinatory effect that will be used in the project?

SdB: It’s just a prescription drug, and I’m using that as a means to not completely describe a character. No one is quite able to describe this main male character, what he looks like, or who he is. He’s the main catalyst for some…marginal activity. That’s how I would put it. I like this idea of never completing, an incomplete portrait and leaving gaps.

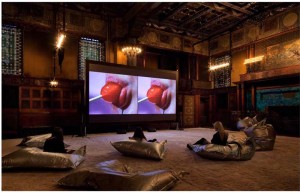

MK: Is it going to be along the lines of “The Ghosts”?

SdB: I think it’ll be a little faster-paced? More violent? I’m not sure; it depends on whom I get for the male character.

MK: And how long are you going to shoot for?

SdB: It’s 8 days. “The Ghosts” was shot for 8 months, a couple days here, a couple days there. Since moving back to New York, I have missed the energy that I had in Berlin, where I would go find an abandoned building and make it a part of the set. I would shoot and then leave. I would shoot in condensed periods of time so everything was lined up, everyone was trapped together on the set. I’m very proud of “The Ghosts.” It’s a project I worked on for 3 years and we shot for 8 months, which was intense. But for this project, I wanted to do something thoughtful, but fast, and to have it in a permanent state of change. It was re-writing itself each day of the shoot.

MK: And “The Ghosts” was made during the stock market crash and in Berlin (where expenses are lower than they are in New York).

SdB: I did do much of it here, too, and it was a challenge. I noticed during that time that, in general, in 2009-2010, exhibited work seemed to be smaller, more drawings, paintings. But what I’ve always done as an artist hasn’t always made sense.

MK: It’s interesting how in New York there are some limitations (such as space), but there are opportunities, like your work with musicians, and all these different kinds of people. Working with other collaborators seems to be a big factor in your work. Perhaps you can elaborate a little bit more on the process of working with some of these people? This man for instance, brings an example of how the outcome changed from the original concept through the process. Does that happen often?

SdB: Yes, every single time. In the process of shooting, the tension of the work changes with the person that I’m shooting. That is exciting to me. In a certain sense, I feel connected to the tradition of portraiture stemming from someone like Diane Arbus, or more recently Rineke Dijkstra, where the subject influences me as I work with them, and the subject defines the work in the end. But because I’m putting it in a filmic context, things like narrative or even environment get shaped partially by people that I’m working with. Part of the process is that I’m pulling things out of them. I talk with people that have strong identities of their own.

MK: I imagine that was what happened with “The Ghosts.” Since it ran over the course of 8 months, did it shift quite a bit from the original concept to the final piece?

SdB: Well, “The Ghosts” more than other ones. It did shift a lot and many people involved in the project had their own strong identities and ways that they shifted the piece. The characters made their own imprint on camera and on footage, although the script was pretty complete. I wrote the whole thing before I started, and Alissa had finished the majority of the monologues, which for the most part stayed in the film. Some things changed significantly in the editing process: the hypnosis scenes, or I wrote this terrible dialogue that I cut out in favor of other pieces of footage. Like the scene with Claire and the lollipop, for example, replaced some text. But this new film is by far the most unstructured.

MK: To get back to the theme of working processes in New York, I’m curious to know the motivating factors as to what brought you to New York in the first place and if that’s something that still resonates today. If it feels accurate of why you’re still living here.

SdB: Well, I moved to New York when I was young, when I was 17. I moved here a bit by accident. I knew I wanted to be an artist but I had no idea what that meant. I went to art school here, both for undergrad and grad.

Once you’ve lived in New York, it’s hard to leave it but it’s also difficult to stay. There is an energy that comes from the street. I loved Berlin, but what I loved most about Berlin from a film-making point of view, was taking the energy of New York to Berlin and then really getting as much as I could out of Berlin, using that driven energy.

There is a cliché about Berlin around coffee, that when you first arrive in Berlin, you go for to meet someone for a coffee, and it takes a half an hour. Then it takes an hour, to two hours, to four hours. And in your personal life, you move from having a romantic love affair to a tragic Fassbinder version of a love affair. I found myself at the end of my time in Berlin having a 4-hour coffee with a friend, weeping over a broken heart, and in this moment I realized it was time to leave and come back to New York.

MK: Did you feel like a New Yorker, or an American, while you were there?

SdB: I felt like such a New Yorker.

MK: To not feel settled or satisfied!

SdB: With anything.

MK: I wanted to talk about some of the different installations you have made in different environments. The High Line piece, “Haunt Room,” for instance, seemed incredible in that space. What was it like working outdoors like that, to create a structure in an outdoors environment?

SdB: I enjoyed it. It was a different kind of audience; it was a broader audience. I was surprised that was the piece that they wanted. It was the most aggressive piece that I proposed to them. The work was an audio tone in a public place that made you feel sick. The curators and the trustees of the board of the High Line believed in that particular piece, and wanted that particular piece. It was creatively challenging, as well; I had never made an outdoor installation before. It’s hard to control audio levels in an outdoor space.

MK: And working with the general public, it’s interesting to prepare something for a gallery exhibition than something that will be on the High Line, even though it’s only a block away. Is that something you were thinking about when you were making the work?

SdB: Maybe. I’m interested in that site. It’s created this new landscape; it’s a new way of looking at the city, at the topography of New York City. I worked on the piece while they were building up the new section and I liked walking through the new section while it was under construction. I am also interested in non-art. Perhaps I find it interesting because I came to contemporary art so late. I feel like the gallery’s audience on the one hand is very rarefied; it’s a small group of people, but one that is open to absorbing different kinds of perspectives.

The only thing I wasn’t thrilled about was they had to put up a warning sign that the audio may make you sick, and I felt like the warning sign created a new dialogue about what the piece was supposed to do. That maybe did a disservice to it. The warning sign said something like, “This artwork might cause depression,” and I think that really for that to happen you would have had to be next to the speaker for significant periods of time. But I think legally, in America, in a public space, you need to present the worst-case scenario.

MK: Your work then often seems inspired by site. You have the space first and then the work is designed for the space- is that usually the situation?

SdB: I love that. It’s like that with shooting, as well, working with people. Making art is a dialogue, the back and forth.

MK: I suppose in the end it is solitary, because it’s you editing, and it’s not a typical studio environment. But you’re still working with people so that you do get continuous feedback and advice.

SdB: I think it’s the working process where I have many people around me or I am literally just working on my bed. I need time alone and then I really need to have people around to get the conversation going.

MK: What are your thoughts in general about the New York art scene? Would you describe it as somewhat collaborate or more disparate? Is there a general feeling about the way that art circles and things move within each other, something pretty natural or maybe not as much as it was say three or four years ago?

SdB: I think it has more to do with age. I know as a young artist my peers were extremely collaborative and in constant dialogue. At a certain point these people’s careers lifted off and it became more paranoid and territorial. I like working at universities because there is a permanently young element engaging in dialogue.

MK: There are so many schools and so many students here, which does create great artistic communities. This is somewhat unusual. For instance, when I’m in Miami there are only a couple schools down there. From the conversations I have had with people I have found that they find that very frustrating so they often bring in people to do talks, panels, in order to create these conversations. Because that is something that they feel is very necessary and needed. From your community, do you get a lot of information or feedback from the students or from the other faculty?

SdB: Yes. I think to be affected by your students you have to be open to it and I think that can be exciting. It also involves humility. On the other hand, you have brilliant people come through and then to be able to watch them develop is it’s own kind of privilege.

You know, I have a group of friends that are artists and I rely on them; they’re pretty key people for me. But in a certain way, in time, you start talking more obliquely about artwork you are working on, and more often the conversations are about whether you have seen a show. Mid-process in the studio is a private time, and you discuss a body of work when you have finished with it. When you’re in your twenties you want to talk about whether you should have used something different in a particular piece; how does the duct tape work for you? It’s specific, muscular, different.

MK: Did you have a film background from school?

SdB: No, my interest in film came about gradually. I majored in painting as an undergrad at Parsons, but I primarily took photographs, staged photographs. And then I went to Columbia for grad school. There I worked with Jon Kessler and Troy Brauntuch. Troy had made this incredible body of work, but when I met him it was a quiet moment in his career.

I shot my first video at Columbia. Initially I just shot myself; I would set up lights, and try things out in front of the camera. But I didn’t really want to shoot myself; I found it to be limiting, too diarist and strange. I think that working in a collaborative team, getting comfortable working with other people, was an important step for me.

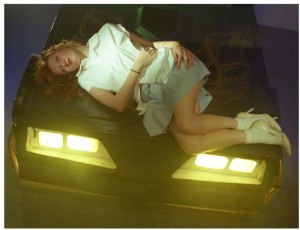

MK: There is a huge influence of modern Goth in your work and I read that you have an interest in horror films like “Halloween”?

SdB: I love “Halloween.” I wish Halloween was every holiday.

MK: Also teenagers, teen fiction novels are an inspiration.

SdB: For a while, it was very important source material. I think that I was interested in adolescence partly through the idea that it is a short window of time, yet is so important.

When I first started shooting other people, they were young people. I was interested in the fragility of that time period, and how exposed they looked on film—raw. Youth is also a radical time, because you don’t have to live with the consequences of your actions; your actions are done in broader strokes. I did a number of works using young people until I became frustrated with the dialogue around my work. I also felt like shooting only young people was becoming a crutch to get that kind of raw-ness in my footage.

MK: There is a kind of parallel with this type of recklessness to horror or gore.

SdB: Yes, you change your life or break it apart in that one moment of violence. I was raised in New England, and New England has a violent history that has marked its sense of aesthetics. Witch trials. There was a heavy religious component that was mixed with the occult, violence between early settlers and American Indians (gory deaths, kidnappings). This was the foundation and it has colored the culture that grew out of it.

MK: So something like The Crucible is an interesting kind of relationship, tying all of that together with teenage vulnerability and femininity. It is interesting that you’re now making a piece in a basement!

SdB: I know. I was so excited. No windows down here, perfect. They had offered something upstairs and I said no, I really want the basement. It’s my dream space.

Interview with Ryan McNamara by Meaghan Kent 6.26.13

Meaghan Kent: There are some interesting distinctions between New York and other cities. You mentioned your exhibition in Rotterdam and also São Paulo?

Ryan McNamara: There are so many differences, where do you begin? In terms of the immediate experience of making something, New York privileges this constant, all-consuming productivity, so, on the surface anyway, it seems quicker and easier to get things done here. We love to brag about how busy we are, how late we worked, etc., which just reinforces this sense of urgency and self-importance.

MK: I wonder if most people intentionally create things to exceed their own level of expectations in order to test themselves. They create a bigger goal in order to find out, “okay, I can do this,” “I can’t do that,” or “how can I be able to accomplish that?”

RM: Constraints are gifts. Sometimes a project is about looking at the structure and the constraints and putting the pieces together like a puzzle. I have to figure it out. In my brain it feels like if I just put all of these constraints together in the right way, the project will be done. I like the idea that it will arrive through those constraints.

Something like “artistic freedom” with no constraints would drive me crazy. That’s more of an author way of working—creating the whole universe. For me, it’s more interesting if there’s a specific building in Rotterdam and the crowd traffic is around fifteen people a day versus Chelsea where there’s 200 people coming through who have probably been to ten galleries already. That audience mindset becomes one of the registers I’m attending to. For instance, I know in Chelsea someone will spend two minutes in an exhibition versus Rotterdam where they come for the experience and are dedicating more time.

MK: That’s an interesting concept to think about in preparing for an exhibition. Other than the space itself, you’re thinking about the time.

RM: Chelsea audiences are more likely to be checking things off the list. We all do it. It’s about getting it done. Like, “I saw that show, that show,” etc., because they’re right next to each other and that’s how the flow works. It’s a unique audience, and whenever I do something there, I tailor the project with that in mind.

MK: So you have an idea and then it becomes designed to the space itself or the project itself?

RM: Someone often proposes an opportunity and I make something for it. I have a few thoughts around the framework of, “Wouldn’t it be great if…,” and I have x, y, and z space to work in. If it’s something individual and it takes ten minutes per person or it doesn’t work if there’s constant traffic of people, then I try to account for that.

MK: You really think about the public, the viewers, and that’s something really special about your work. The outcome must really change from what you imagined it to be, so it varies a lot. In Rotterdam, for instance, were you really surprised?

RM: For the project at Showroom, MAMA, in Rotterdam (“Survey: Personal Performances”), people could either do it online or in person. You filled out a questionnaire about what kinds of “ingredients” you like in performance, and in five minutes we put something together. It worked for the space, which had two rooms, one of which was a “performance” room and the other more like a doctor’s waiting room. For people who participated online, we had a wheelchair with a camera attached that would move around the space so you could watch it livestream. It’s totally “interactive,” a bastardized word with terrible connotations, but one I also like for its ridiculousness.

I made up the parameters for this project, but didn’t specify the design of the actual questionnaire. When I showed up and saw the form, it was not at all what I was envisioning. It had a crazy Japanimation theme. These are my questions but this really isn’t my design. It’s part of setting up projects and leaving some things unknown.

MK: But you do look at it optimistically.

RM: I was shocked but it was so amazing and anti-my aesthetic; I was into it.

MK: And thinking about “Still,” the exhibition you did at Elizabeth Dee Gallery, you had so many people coming in.

RM: I can’t sit in a chair all day, so I do these long-term projects that are more interactive. With performance, unique individuals come in and add something to the project. How could you not exploit that?

MK: When I went there, I had a press person waiting behind me. And online you see all the pictures with people: big collectors, curators, and advisors. Everyone was a part of it, on the same level, and not taking things too seriously.

RM: That was important for me. I set up a structure with some very basic rules that allows for millions of opportunities. It was crucial that there was no audience; only people who participated were allowed in the gallery, so participants could perform without being watched. If people weren’t willing to participate, they couldn’t come in. We had a card that said, “Thanks so much for coming, you can experience the project online.”

MK: The Internet becomes this whole other realm, too. You’re viewing the work or becoming part of the process in your private home. That has now become a big part of your work.

RM: “Survey” opened up something new for me. I often respond to the behaviors of audience members and work with people who know how to read an audience. Performing for an online audience is like doing it blindfolded. You don’t even know if people are actually watching. They could be in the bathroom while we’re doing this.

My favorite thing about performance is that it’s this specific time with these specific people, but how does this line up with where we are now culturally, trying to stay connected at all times? This project was sort of mocking aspects of this digital existence, people getting used to customizing things. The email invitation played with this: Create whatever kind of performance you want, whenever you want. There’s a parallel shift within museums, using audience surveys as a marketing strategy. There is now a trend within marketing departments to nail down the museum’s demographics, presumably so they can better tailor the experience. In the Netherlands, museum marketing departments are developing now, and they want to know who the audience is and that’s an interesting shift. This project takes this idea further, hyperbolizes it, gathering the audience information before the work is even made. Of course, at the end of the day, it’s still my performance.

MK: Have you ever done any kind of improvisation?

RM: No. A friend of mine is into improv classes, and I thought about taking one. In theory, I thought it was a wonderful idea but there’s something about it that doesn’t sit right with me. Performance isn’t solely about entertainment, and I find the eagerness of improv to entertain a bit overbearing. That’s the thing about art: You minimize certain kinds of expectations. You know a TV show that doesn’t entertain is a bad show, but a work of art that doesn’t “entertain” can still be provocative, and in turn, be considered a “success.” Improv always anticipates a certain reaction.

MK: And there’s something about improvisation where watching it can be really uncomfortable and you sense the failure. But with art, failure is an important part of it.

RM: If everything is an experiment, there are no failures. If there is no set goal, then how can there be a failure? I would be into a brand of improv where they bore you. Not so say that I’m against art that entertains. I’m very much for it.

MK: Well then, what do you think came out of something like the project at Elizabeth Dee Gallery?

RM: For me, or for the world? There were a lot of people who weren’t accustomed to a less habitual mode of performance, and that was a challenge. I had to be really outgoing. For “Survey,” we were working so quickly, I was doing things I wouldn’t normally do in a performance because the survey dictated the parameters. So both projects pushed me out of my comfort zone.

Doing a project in Rotterdam, I had to really love the experience. I wasn’t going to sell anything; I was going because I wanted the experience. The goal is the project. Being in the moment is critical.

MK: The idea of “being in the moment” ties back into New York, which I believe is impossible to do here. You are always thinking about the next thing.

RM: I think that that’s kind of amazing. On those days when I’m performing, it’s so much work to allow myself to be completely in the moment. For Rotterdam, getting the survey to only be five minutes was so important, and there’s nothing more in the moment than that!

MK: How many did you do?

RM: We did 75 performances in five days. There is a show of the aftermath up right now; you can still view it online. The livestream is on at all times, so even though no one’s performing in the space now, you can still get a glimpse of this crazy environment of props. I wanted to make it like an installation where all the tools are here for you to do what you want with it. It’s not about just showing performance footage, but trying to find a way to create situations that are as engaging as the performances were. That’s a challenge, how to make a show that’s not, “Oh, you missed something.” I’m always trying to figure out how to do that. My background was in visual art. I started with photography and then moved toward “performance art,” whatever that is, but I never lost my interest in making things.

MK: So you still make physical work through decoupage. But that’s something you haven’t done before?

RM: That’s one thing I think is so funny: the idea that performance is ephemeral. I’ve been in so many costumes and used so many props. Sure, my body in that moment is gone, but there is a lot of residue. At a certain point the costumes become retired from performance. I still have an attachment to them, so I want to give them a new life as an object.

Decoupage is about merging the residue (the props and costumes) and the documentation, the still image. I harden them. Gravity helps it form. We use balloons to structure the works. It doesn’t feel like we’re hoarding, but instead creating an inflation of the environment.

MK: Popular culture comes into play quite a bit.

RM: I think what interests me about pop culture is that it instantly sets a tone. It’s something shared between you and the audience member—not always, but you’re far more likely to have that in common. What I also love is working with not-so-popular culture—it sounds like something you’ve heard before, but the tone is more implicit. It’s tied to what you know but you might not know, like something new yet familiar, setting the tone and the era, but you can’t put your finger on it.

MK: You’re originally from Arizona. What made you want to move here and what keeps you here?

RM: All sorts of haphazard yet specific moments. My mom told me that if I did Publishers Clearing House, I could get one magazine, and I chose Interview because it was the thickest and it was exciting in the early 1980s. I kept that subscription so I was weirdly tied to New York. There was also the documentary “Paris Is Burning.” And when I was around 9, I watched the “Club Kids” episode of Geraldo Rivera and I wanted to move to New York. Those three things really made me want to come here, but they’re not the reasons I stayed. New York is the best city to be an audience member. It’s a crucible of dance, film, art, whatever. I collaborate so much with others and the talent base of New York—there is nothing like that anywhere. So as a performer and collaborator, the city supports me.

MK: You said once in a quote from 2009, “The New York art scene is disparate geographically.” Do you think this is still true?

RM: Sure. That was a weird year for me. The next year I was in “Greater New York” at PS1, and that show made a big difference because I became a part of something with artists my own “age.” I already knew some of them personally, and we would be in each other’s works. Geographically though, we aren’t all in the same place, not like the East Village or Greenwich Village or Soho. Those times of mingling through physical proximity, of neighborhoods articulating certain kinds of contact, are mostly over.

Now you have to make it a point to see someone; it doesn’t just happen. We aren’t all at the same bar together. We don’t just hang out; we go to dinner and openings and performances. You have to say, “I want to work with you.” It’s more professional because it’s the project first. I have to say, “I am interested in this world and I have to make myself a part of it.” Knowing that I belong to this group from “Greater New York”… I don’t want to say a generation of artists because that brings up age. It’s more about a connection of ideas.

MK: How did you meet Robin Bird? There is a New York icon!

RM: I came to NY for the first time when I was 15 or 16, and I had a friend going to SVA and she showed me Robin Bird’s cable access show. At that age, sex was terrifying and she was so fun about it. She’s the queen of Fire Island. She has a house there. Pati Hertling asked me to do a benefit for the Fire Island Pines Performance series and Robin Bird came, and I was completely star struck. She was so great and friendly, and gave me her address. It was amazing.